By Barry Draycott

Have you ever plant a seed that took forever to germinate?

Have you ever plant a seed that took forever to germinate?

Way back in 1979, while I was earning my degree in Environmental Studies, one of the required reading books was The Closing Circle, Nature, Man & Technology, written by the ecologist Barry Commoner.

Commoner addressed the environmental crisis and humans and nature’s interaction on many different aspects: including population growth, consumer demand, politics, capitalism, greed, and other factors. He sums it up with this quote:

In the book, he formulated the Four Laws of Ecology.

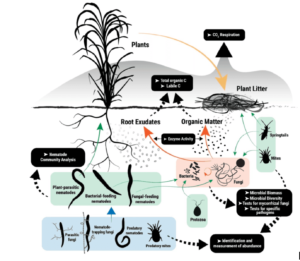

The first of these informal laws, Everything is connected to everything else, indicates how ecosystems are complex and interconnected. This complexity and interconnectedness are not like that of the individual organism whose various organs have evolved and have been selected based on their contribution to the survival and fecundity of the whole. Nature is far more complex, variable, and considerably more resilient than the metaphor of the evolution of an individual organism suggests. An ecosystem can lose species and undergo significant transformations without collapsing. Yet, the interconnectedness of nature also means that ecological systems can experience sudden, startling catastrophes if placed under extreme stress. “The system,” Commoner writes, “is stabilized by its dynamic self-compensating properties; these same properties, if overstressed, can lead to a dramatic collapse.” Further, “the ecological system is an amplifier, so that a small perturbation in one place may have large, distant, long-delayed effects elsewhere.”

The second law of ecology, Everything must go somewhere, restates a basic law of thermodynamics: in nature, there is no final waste, matter and energy are preserved, and the waste produced in one ecological process is recycled in another. For instance, a downed tree or log in an old-growth forest is a life source for numerous species and an essential part of the ecosystem. Likewise, animals excrete carbon dioxide into the air and organic compounds into the soil, which helps sustain plants upon which animals will feed.

Nature knows best, the third informal law of ecology, Commoner writes, “holds that any major man-made change in a natural system is likely to be detrimental to that system.” During 5 billion years of evolution, living things developed an array of substances and reactions that together constitute the living biosphere. However, the modern petrochemical industry suddenly created thousands of new substances that did not exist in nature. Based on the same basic carbon chemistry patterns as natural compounds, these new substances enter readily into existing biochemical processes. But they do so in ways that are frequently destructive to life, leading to mutations, cancer, and many different forms of death and disease. “The absence of a particular substance from nature,” Commoner writes, “is often a sign that it is incompatible with the chemistry of life.”

There is no such thing as a free lunch. The fourth informal law of ecology expresses that the exploitation of nature always carries an ecological cost. From a strict ecological standpoint, human beings are consumers more than they are producers. The second law of thermodynamics tells us that in the very process of using energy, human beings “use up” (but do not destroy) energy, in the sense that they transform it into unworkable forms.

For example, in the case of an automobile, the high-grade chemical energy stored in the gasoline that fuels the car is available for useful work while the lower grade thermal energy in the automobile exhaust is not. In any transformation of energy, some of it is always degraded in this way. The ecological costs of production are, therefore, significant.

I found these laws to be very interesting in general. However, Commoner went into a very detailed analysis of these laws’ impact, so I put it away after reading it and continued with my education. But the seed was planted.

After graduation, I chose a career in the landscape industry because I loved being outside and doing physical work. Over time I was promoted to manage the pesticide and fertilizer division for a few tree care companies. Over the years, I saw our industry slowly evolve from blanket treatments to spot treatments and plant health care programs.

Eventually, I founded my own company about 15 years ago, which specialized in organic treatments, after becoming a NOFA Accredited Organic Land Care Professional and attending several of Elaine Ingham’s, who is a leader in soil microbiology, classes. The company gradually morphed into a supply company.

During this time, I began to use the phrase “Everything is connected to everything else” at the end of presentations and emails. I had forgotten where I had heard the phrase, so I Googled it and was reintroduced to Commoner’s book.

The seed was watered. Last year I found a copy of The Closing Circle, Nature, Man & Technology and started reading it again. I was stunned to find in the first chapter even before he states the Four Laws, Commoner discusses the fundamental interaction of nutrients, humus, soil microbes, plant health, and climate! Remember, the book was published in 1971!!

The seed sprouted! People have known about the negative impacts we have on land for quite some time, yet we are only now beginning to grasp the adverse effects it will have on all our lives if we continue to ignore ecosystems. The good news? Our industry has come a long way since then. More consumers are asking for fewer and less harmful pesticide treatments. Our industry is learning how important it is to improve soil health and, even more importantly, how to achieve healthy soil.

Last year was a challenging year for many reasons. But let’s look towards the future and continue to learn how to improve and implement actions that provide positive results. I’ve learned that the only things we have complete control over are our own attitudes and determination.

Remember: “Everything Is Connected To Everything Else”

About the Author

Barry Draycott is the owner of Tech Terra Environmental (TTE), founded in 2005. Techterra Environmental provides ecological solutions for landscape professionals with organic soil amendments and pollinator-friendly insect control products. They can customize your application program to meet your specific requirements. Barry’s career in the green industry began in 1977 as a pesticide applicator for a New Jersey tree care company. For decades Barry looked for ways to improve plant vigor and reduce pesticide usage. This led him to scientific research, which demonstrated the positive impact improving soil health has on plant vigor. Barry made 2021 his “Year of Renewal.” This means that he has recommitted to the company’s #1 goal: providing landscapers, schools, and now the agricultural industry with the knowledge and products that will help grow business while protecting our environment and our health.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute an endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.