By Marie Chieppo

In 2019, the Association of Professional Landscape Designers (APLD) sustainability committee asked me to research and write about plastic horticultural pots use and disposal methods.

The APLD published a research paper in July 2020 entitled, “Plastic Pots and the Green Industry: Production, Use Disposal and Environmental Impact.” It was through the use of plastic containers that the horticultural industry grew as quickly as it did. Before plastic, growers used metal cans and clay pots to transport their products. Or, sold plants with bare roots covered in a slurry.

A vessel that doesn’t break, is hydrophobic, comes in multiple sizes and shapes, is inexpensive to produce, and easy to transport was a game-changer. Now, plastic is all we see for container types when we purchase material. Their beneficial characteristics resulted in billions being produced without a blueprint for what would happen as demand increased.

Unfortunately, we’ve produced so much plastic that we can’t possibly recycle it all. We don’t have the capacity; post-consumer recycled (PCR) plastics are worth very little, each item must be cleaned and sorted, and companies are paying to dispose of them. The United States, on average, recycles only 8.5% of its plastic waste. Black plastic pots don’t even make it through the recycling machinery. Optical readers cannot identify the carbon pigment. Additionally, they are composed of mixed-used plastics, rendering them impossible to process. Our industry needs viable alternative options.

What About Biodegradable Pots?

What About Biodegradable Pots?

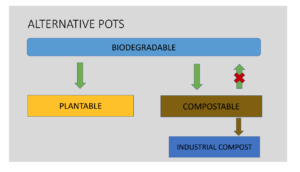

Biodegradable pots have been in the market for several years. Typically, they are either plantable or compostable and made of naturally-based materials. For the most part, they are used for small scale operations and sold to individuals or small retailers. To assess their compatibility on a larger scale, trials were conducted in greenhouse production facilities that compared their durability, water use, production efficiency, and plant performance to plastic containers. For the most part, plant growth was comparable. There were concerns about water use and environmental factors that impacted plant growth and appearance. Plants that were grown in wood, pulp, fabric, and coir containers, not surprisingly, used more water. In terms of container integrity, the rice hull performed the best. Bioplastics, a material we aren’t terribly familiar with, also maintained container integrity.

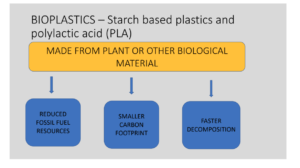

Characteristics of bioplastics are similar to those of traditional plastics. They are created either from biopolymers (plant or other biological material) or a blend of bio- and petrochemical-based polymers. Depending on their chemical makeup, they may be nonbiodegradable, durable, biodegradable, or compostable in an industrial setting. They are much more eco-friendly in terms of less use of fossil fuel resources, a smaller carbon footprint, and faster decomposition than a petroleum-based product. Another plus is they can be processed on currently used machinery, and companies have been manufacturing these pots for the commercial sector. Options include those certified for organic growing by the USDA (fiber, water, and natural resins) and are 100% biodegradable and compostable and others with greater durability that contain a non-organic binding agent. Hopefully, these will prove to do well on the commercial scale and reduce the amount of petroleum used in pot production.

Truly Recyclable Pots

The UK heralded a more sustainable pot using a single type of plastic. The Taupe Pot (strictly made of polypropylene ) is a relatively new standard container. The mission is to replace the black plastic pot with one that is being recycled into other usable products after a single use. As long as they are polypropylene, they can go back into the waste stream. Perhaps standardization would be helpful here, too.

With standardization, the difficulties associated with sorting and collection would be greatly lessened. Recycling companies like East Jordan Plastics in Michigan primarily recycle used horticultural plastics. Most of their material is retrieved from big box stores where customers return used plastics. Utilizing a combination of other used materials, they produce new pots. Other companies that recycle these plastics do exist, but not enough to sufficiently dent the amounts we produce.

Know Your Materials

A survey conducted at the University of Georgia found that most growers and landscapers know very little about alternative pots. These are not on their radar.

Where do we go from here? There is no magic bullet, but the APLD is forming a campaign to collaborate with green industry professionals to help determine our next steps. The goal is to reduce the demand for plastic pots effectively. The hope is to have 100% renewable products that meet high-performance standards that are produced efficiently. Until we get there, perhaps we can try to find better ways to reuse what we have, perhaps learn more about bioplastics. It appears that the next logical steps are education, conversation, and collaboration.

About the Author

Before discovering her love for gardening, Marie Soulliere-Chieppo was the researcher for the Editor in Chief at the New England Journal of Medicine. For the past 23 years, she has been a landscape designer and horticulturalist with a passion for healthy landscapes. As a member of the Association of Professional Landscape Designer’s Sustainability Committee, she was asked to research the issue of plastic horticultural pots, their disposal, and how their use impacts our environment. For six months, she plunged into this issue and made some jaw-dropping discoveries. The white paper entitled, “Plastic Pots and The Green Industry: Production, Use, Disposal and Environmental Impacts” was published in July 2020.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.

What About Biodegradable Pots?

What About Biodegradable Pots?