Maintaining and Monitoring the Project

by Lisa Cowan, PLA, ASLA

At a recent meeting with fellow landscape architects, there was a lengthy discussion and agreement about the importance of maintenance and follow-up monitoring for project success. That discussion was primarily focused on the challenges of ensuring good maintenance on traditional site development projects.

Equally important for ecological restoration! However, ecological projects require another set of methodologies that are not standard industry practice.

As a follow up to Mill Brook Restoration – Strategies for Success, Part 1: Defining and Executing the Project, which appeared in the October 2012 Newsletter, I was asked to expand on some of the more innovative follow-up and maintenance approaches that we have used successfully. This discussion is not limited to what was done on the Mill Brook project (which was one of our first), but has drawn from lessons learned on Mill Brook and other projects with similar maintenance challenges.

For this subject I consulted a fellow teammate – the wetland scientist and wildlife biologist who was on the team responsible for the permitting, design and monitoring of over 30 wetland/upland/riparian restoration projects – large and small. The following categories stood out: Plant Layout and Mulch, Plant Performance Guarantee, Invasive Plant Control and Hydrology.

The best way to reduce maintenance is to address it during the planning and design phases of a project, because there is where you have the best opportunities to set up systems that reduce time and costs.

Plant Layout and Mulch

After spending too much time looking for new plantings on the 17-acre Mill Brook restoration site, we concluded that a more systematic approach for plant layout was needed. We were looking for a system that could be adapted to both large and smaller sites. On our next set of projects we experimented with the concept of creating plant groups that would be repeated in a random fashion. We found this method to be so successful that it became standard practice on all of our sites.

We determined that the plant group concept has several important advantages that help reduce maintenance. Group planting is an organized system that:

- Makes it easier to mark, find, count, document, and maintain large numbers of native plants. This system worked especially well if the site was being maintained by landscape laborers who were not familiar with native plants.

- Concentrates plantings into a smaller area thus reducing inputs such as mulch, use of equipment, labor, and water.

- Concentrates plantings into a smaller area, helping woody plants to achieve closure and shade out weeds more quickly.

- Establishes distinct woody plant zones and herbaceous plant zones. If mowing is needed, the woody plants (being in groups) will not be damaged by those practices.

It takes some math to come up with the number of groups, size of the groups, and configuration of plants in each group. Start with the target density of woody trees and shrubs per unit area to determine the number of plants required. In our case, this number was based on goals set up in the mitigation permit process, and for a forested wetland a typical planting density was approximately 400 trees and 100 shrubs per acre.

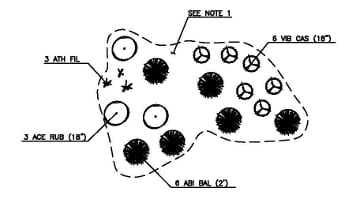

Early on we decided to limit the number of species in each group to keep things simple – with only three to five woody species in each group. We would tweak the number of groups and the number of plants in the groups based on the density goals and the site configuration. The illustration below is an example of a typical mixed tree and shrub group that included a total of 15 woody plants per group. (Note: the example below includes also includes three Athyrium filix-femina (ATH FIL) or Lady-Fern.)

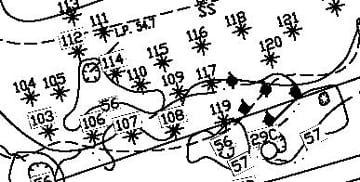

Each plant group was marked with a grade stake, with a number, and with the type of group. It became easy to memorize what belonged in each group type after a few site visits, so plant counts were streamlined.

We also used the plant group model for monoculture plantings like Cornus sericea (Dogwood) or Salix (shrub willows), but we changed the size and number of plants within a shrub group to get the appropriate density. We usually used large numbers like 20 to 50 shrubs per group, depending on the ecological goals.

Next, we developed as-built monitoring plans (also used for maintenance) that showed the location of each plant group. On larger sites we used GPS to accurately determine locations. As the site herbaceous vegetation grew and it became harder to find the groups, these plans became very important tools for maintenance and management.

As most of us know, mulch is critical to reduce weed and grass competition and to keep the soil from drying out during the establishment period. As stated above, the plant group concept reduced the amount of mulch needed and therefore set up better conditions for plant success.

The type of mulch we used would vary, depending on the ability to bring trucks and other equipment on the site. We have used traditional bark mulch, compost, and wood chips (on higher nutrient soils, such as pastures where grass competition is aggressive), and mulch mats (a geotextile used in the forestry industry). The result was better survival, less weeding, and improved plant performance.

Plant Performance Guarantee

Years ago the Maine Department of Transportation (Maine DOT) changed their standard plant specifications from a one-year plant guarantee period to a two-year plant “performance” guarantee. As with any state agency, those sorts of changes go through a rigorous review process, so we can assume that it was demonstrated that the extra cost for another year of guarantee would be far outweighed by the savings.

Maine DOT found savings by changing how they monitored the plant installation process. Under the old one-year plant establishment requirement, Maine DOT used professional staff or consultants to observe and document plant installation – because it was how they ensured that the plants were planted correctly and would therefore survive past the one-year guarantee. This practice resulted in many hours of on-site inspection and documentation and thousands of dollars of expenditures. To remedy this situation, Maine DOT determined that with a two-year performance guarantee, they could eliminate the oversight during installation and get the benefit of the longer maintenance period.

Under the new (two year) system, Maine DOT’s plant specialist inspected plants before planting. The plant specialist also marked all plant locations (with color coded wire flags), but did not directly observe planting operations. Installed plants were counted after planting, and the contractor was responsible for maintaining and replacing all dead and diseased plants during the two year plant establishment period.

This has been a highly successful practice for Maine DOT projects. We also followed the two-year performance model for our ecological restoration work and there were similar results – reduced monitoring costs during installation and better overall plant performance.

Invasives

Now more than ever, every ecological restoration project must include a plan to control invasives. I would highly recommend that the design and monitoring team include an invasives expert– someone who is well versed in the science and field techniques for invasive plant control, so they can advise on reasonable expectations and level of effort. By getting the right advice you could potentially save a lot of money and time, which would more than pay for the cost of the expert. Sometimes an expert can be found through government sponsored programs like the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), but because of limited budgets one should not expect to rely on them for individual project consultations.

Example of a small plant group. Mulch mats (a geotextile product) were used because of limited access. Existing grasses were left around plant groups to reduce the possibility of opening the entire site up to erosion and invasive plant infestations.

Because each invasive has its own specific type of control, the strategies below focus on prevention:

- Do not allow the use of hay as mulch. Hay will include a variety of plant matter and seeds and you could be importing an invasive plant to your site unwittingly. Do not let contractors talk you into accepting hay on a site, even if they say they know what is in it. You have no way to confirm their claim (which could be well-intentioned, but not provable). Straw is one of the most widely available alternatives for mulching large areas after seeding. Hydro-mulching is an option that is dependent on site access for equipment. I would be curious to know if people have had success with other types of mulch that are invasive-free.

- Think ahead and create specifications and plan notes that address the contractors’ responsibilities if invasives are brought on site from imported soils, soil amendments, or seed and mulch materials. Then if an infestation from these sources occurs, you have recourse.

- Repeating what was covered above under Plant Layout strategies: the quicker the coverage by desirable plants the less likely invasives can take over, whether it is woody plants or the herbaceous plant layer. Years ago a very wise ecological plant expert advised me to prioritize coverage of a site with desirable plants, either through planting or seeding. I would also include some pioneer species in both the woody planting and seed mixes; they can provide coverage and shelter to slower growing climax species if not applied at too high a density.

Hydrology

There are many aspects of water that should be considered in follow-up and maintenance, but this discussion is limited to the effects of water flowing onto and through a new project site.

Moving water can have a devastating effect if the site is not established. Prevention is always better than repairs, but “over design” (excess use of stone or geotextiles) is not necessarily the right answer.

Assume there will be a need for follow up repairs during the first couple of years (often handwork repairs are all that is needed with a good design). Bring your clients along with an early discussion about overdesign versus smart design (that accepts some risk), so they will be amenable to a plan and a budget for follow-up work.

This conversation is mostly critical where water is concentrating and has the potential to flow and scour. Sometimes it is desirable to armor the edge of a stream with stone or something like coir rolls, but these methods tend to be expensive and, in the case of too much stone, permanent and not natural-looking. Consider a combination of permanent natural materials like local stone, with products like jute mesh, wood excelsior, wattles, or brush mats – natural materials that eventually degrade but help to hold soil during site establishment.

A good balance of stone and other natural erosion control materials for stream stabilization is preferable to overuse of stone and geotextiles that are permanent.

Expand the Team

A successful ecological restoration project that results from good design and efficient maintenance practices is the goal. A multi-disciplinary team with expertise in these practices can reduce the amount of trial and error. Usually multi-disciplinary teams are standard practice for larger restoration projects, but I propose that it should be the model for smaller projects as well. Ecosystems are complex, and a few hours with an experienced practitioner can anticipate critical problems and create innovative solutions. Reach out and network with other like-minded professionals. I know from my experience that many people involved in the ecological landscape industry are willing to find ways to consult without costing the project a lot of money.

Another closing point: Seek out and direct business to those maintenance firms that practice in an environmentally sensitive way. It might help to engage our clients in a dialogue about why low bid maintenance contracts do not translate to project success. Then we must continue to strive individually for efficiencies (and share them in venues like this!) so that ecological restoration can be viewed as a sustainable and practical way to be good land stewards.

Millbrook Restoration – Strategies for Success, Part 1 Defining and Executing the Project appears in the October 2012 issue of the ELA Newsletter.

About the Author

Lisa N. Cowan, PLA, ASLA, is the Principal of Studioverde – a collaborative of landscape architects and site sustainability professionals. Studioverde has offices in Cumberland, ME, and Austin, TX. Lisa is also an Officer in the Sustainable Design & Development Professional Practice Network with the American Society of Landscape Architects. She may be reached at Lisa Cowan lcowan@studioverdelandscape.com.