by Rebecca Lindenmeyr

Habitat fragmentation is a serious problem across the country and a significant contributor to the loss of biodiversity worldwide. Here in Vermont, development in the Burlington area continues to fragment the habitat blocks that remain. Preserving as much forest and open land as possible is of course the first line of defense, but in many situations the damage has already been done and then the goal becomes finding ways to reconnect the fragments.

In our favor as Vermonters, we really love our wildlife. In a survey completed in 2002 by the Vermont Biodiversity Project, 97% of Vermont residents surveyed indicated that it is important to them that ecologically valuable habitats and lands are protected, and 75% said that habitat must be protected even if it reduces the land options of landowners. Wow. I find that most of my clients agree, and they would like to preserve habitat continuity in their residential landscapes, especially if it doesn’t overly restrict the use of their property.

Hedgerows as Habitat Connectors

In a previous article, Reintroducing Hedgerows to Residential Landscapes, I described why I feel we need messy biodiversity in our landscapes and the role that hedgerows can play in biodiversity restoration. Hedgerows can also be used to connect fragments of habitat that have been severed by human development. This article describes how we are designing a habitat hedgerow on a new piece of property we recently purchased in Shelburne, Vermont. Our goal is to create not only a new homestead/design studio but also an educational venue to show clients how Principles of Ecological Landscape Design and Sustainable Agriculture work on a typical piece of rural property, and how those lessons translate to other properties in the Champlain Valley.

Here’s what our first concept landscape plan looks like:

At the bottom of the design you can see the proposed Habitat corridor planting or “habitat hedgerow”. A habitat hedgerow can connect wildlife populations separated by human activities or structures. Our new property in Shelburne sits between two established habitat blocks. One block is a dense Hemlock forest that borders the east shore of Shelburne Pond and provides winter protection to deer and many species of birds. The other block is a patch of forest to the east of us across the road. Here’s a zoomed out image that shows the established habitat blocks in the area:

Developing a Plan

Here’s our strategy for creating a Habitat Hedgerow to connect the two blocks – the design process could be adapted for hedgerows in the Northeast:

- Locate existing habitat blocks on BioFinder.

- Connect habitat fragments with a corridor. We decided to widen an existing narrow hedgerow to a width of 50 feet.

- Shape the edges of the corridor with a staggered mix of trees and shrubs in a wavy random pattern. These “soft” edges create more surface area along the edge, and provide pockets that will foster greater biodiversity than a straight edge.

- Add Native Plants to the corridor based on existing natural plant communities. For Vermont plantings we recommend using Woodland, Wetland, Wildland – in other areas you can make a query to the Natural Heritage Inventory). Our hedgerow connects Clayplain Forest, so we’ll use Marc Lapin’s Clayplain Forest Project’s planting guidelines, see below).

- Tailor Design for Passage Users. Our biggest challenge is that Route 116 divides the corridor. We don’t really want to encourage deer to cross a major road. (In an ideal world there would be an underpass for wildlife, but the cost is prohibitive.) Instead, we will focus on providing habitat for birds and pollinators that can fly from tree to tree. Turtles and amphibians might also attempt to cross the road seasonally to get to breeding and nesting sites, and so we will monitor and ask for signage if they need extra protection.

- Tailor Design for Corridor Dwellers. Certain reptiles, amphibians, birds, insects, and small mammals can spend their entire lives in linear habitats. In this case, the corridor must include everything that a species needs to live and breed, so we will select plants that will provide food, cover, and nesting sites, especially mast for small mammals and fruit for migrating birds.

Our Plant List

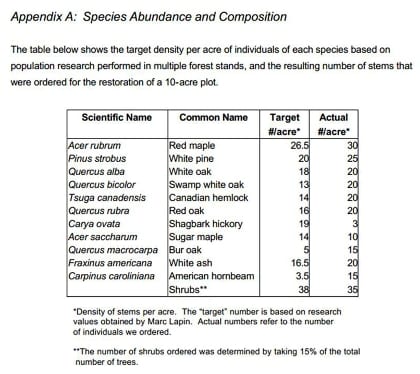

Our hedgerow measures a total of 1.75 acres, and according to Marc Lapin’s research on Champlain Valley Clayplain restoration, our target density should be 250-280 trees and shrubs per acre with shrubs comprising 15% of the total number of trees. Here’s what Lapin’s model plant list for trees looks like:

The placement of each species is determined primarily by their tolerance of soil moisture. In general, Clayplain shrubs are more tolerant of wet soils than trees (with Swamp White Oak being the exception), and we have a large stretch of wet clay to cover, so we will plant a higher concentration of native Clayplain shrubs (35% of the total 250 per acre) and Swamp White Oak than Lapin’s original model. Since the structure of a hedgerow is more similar to a forest margin than a dense forest stand we want to include a higher percentage of margin shrub species in our plant list. This distribution also matches our habitat goal of providing soft mast (berries) for adult birds and oak leaves for caterpillars (baby bird food).

Here’s what the plant list looks like for our 1.75 acre Hedgerow:

| Trees & Shrubs |

Target # per acre |

Actual # to be planted on 1.75 acres |

| Acer Rubrum |

26 |

46 |

| Acer saccharum |

14 |

25 |

| Carpinus caroliniana |

4 |

7 |

| Carya ovata |

19 |

33 |

| Fraxinus americana |

16 |

28 |

| Pinus strobus |

20 |

35 |

| Quercus alba |

8 |

14 |

| Quercus bicolor |

21 |

37 |

| Quercus macrocarpa |

5 |

9 |

| Quercus rubra |

16 |

28 |

| Tsuga canadensis |

14 |

25 |

| Total # of trees |

163 |

285 |

| Amelanchier canadensis |

8 |

14 |

| Aronia arbutifolia |

8 |

14 |

| Cornus amomum |

8 |

14 |

| Cornus racemosa |

12 |

21 |

| Cornus sericea |

12 |

21 |

| Hamamelis virginiana |

15 |

26 |

| Ilex verticillata |

8 |

14 |

| Prunus virginiana |

8 |

14 |

| Salix discolor |

8 |

14 |

| Viburnum lentago |

8 |

14 |

| Viburnum dentatum |

8 |

14 |

| Total # shrubs |

87 |

180 |

| Total Trees and Shrubs |

250 |

456 |

In addition to trees and shrubs, we will add a selection of 300 herbaceous perennials (six varieties, in 50-ct plugs) to help provide sources of nectar, pollen, and forage for pollinators and seed for birds. These include Asclepias incarnate, Aster novae-angliae, Eupatorium purpureum, Monarda fistulosa, Rudbeckia pinnata, and Solidago rigida.

Implementation

In general I prefer not to draw a detailed planting plan for designs like this, but rather gather the materials and lay it out on-site. There are so many variables that come into play including the exact location of existing trees and shrubs, wind patterns, low moist spots, existing boulders, etc. I can take all of those factors into consideration once I’m at the site.

The next question many clients ask is what a habitat hedgerow containing 285 trees and 180 shrubs and 300 perennials covering 1.75 acres will cost. Our answer is not as much as you might think. If the hedgerow was planted with nursery stock from a local nursery (7- to 10-gallon trees, 2-gallon shrubs, and 1-gallon perennials), it could cost about $20,000 in plants alone. In most cases clients prefer to select a lower cost-option for these outlying areas of their landscape. If we use smaller restoration stock plants (mostly tubelings and some 1″ caliper 5-gallon trees, and 5″ deep wildflower plugs in flats of 50), then a ballpark estimate might be $6,000 for the 1.75 acre hedgerow planting described above, including all plants and the labor to plant them. We believe that’s a reasonable investment for our wildlife and a beautiful feature on our clients’ properties that they will enjoy for years to come.

We are really looking forward to observing the progression of this design over the next five years, both with our clients and with other professionals. There will be many opportunities for research, both formal and informal, and we can envision weekend workshops with local ecologists, wildlife biologists, landscape architects, horticulturists, green builders, and organic farmers and homesteaders. Working together, we’ll hope to answer many questions. Which species transplant well and which self-propagate readily? What are the best invasive plant controls? Which species of wildlife show up first and which establish breeding populations? Is the hedgerow wide enough? Should we spread the wild elm seeds or introduce more disease resistant varieties? What species of butterflies should we be looking for, what should we plant for them, where and in what quantities? We hope you can visit us in Vermont to share in our hedgerow adventure.

About the Author

Rebecca Lindenmeyr is co-Principal of Linden L.A.N.D. Group, an ecological landscape design/build firm servicing the Burlington area of VT. Rebecca spent nine years working as a consultant to the EPA and the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources before transitioning into her career as a landscape designer. She is a VT Certified Horticulturalist and has served as President of the Vermont Nursery and Landscape Association. Linden L.A.N.D. Group specializes in Northeastern native plants, meadows, green roofs and green walls, invasive species removal, and the creation of outdoor living spaces that pair beauty with function. Rebecca may be reached through her website: www.lindenlandgroup.com.