Tackling two of the greatest threats to biodiversity

Carrie will present Implications of Climate Change for Invasive Species at ELA’s Conference & Eco-Marketplace on March 3.

By Carrie Brown-Lima

Invasive species are on the rise as trade and travel accelerate the introduction and spread of new species in a way never before seen in the history of man. Simultaneously, our climate is changing at an unprecedented rate resulting in climate extremes – milder winters with extended growing seasons, warming waters, increased CO₂ levels, and glacial and sea ice melting. While these two phenomena are each daunting challenges to biodiversity and ecosystem health on their own, together their impacts can act synergistically and present additional hurdles for conservation and sustainability.

Over the past two decades, substantial evidence has accumulated showing that climate change will both directly and indirectly influence the introduction, establishment, spread, and impact of all taxa of invasive species, ranging from forest pests to terrestrial plant species. However, the specific circumstances under which invasive species are impacted and strategies to circumvent some of the impacts are still being explored. Many landowners and managers, planners and growers, and policymakers are actively seeking answers on the best ways to prepare for these changes in order to incorporate climate change into their invasive species policies and management plans. However, a clear understanding of what these changes will be is necessary to come up with solutions.

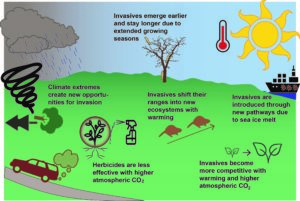

Figure 1: Major interactions between non-native invasive species and climate change. (Bradley et al. 2020)

According to Bradley et al. 2020, there are six major ways that invasive species and climate change are predicted to interact:

1) Paving the Way: With the melting of sea ice in the Arctic, new introduction pathways are created, providing a new route that connects Asia directly to the East Coast of the US. Because invaders often catch a ride in ballast water and packing material, this new, shorter route could be an express train for new pests coming into the country, increasing their likelihood of survival in-transit.

Example: Zebra and quagga mussels are currently negatively impacting Great Lakes ecosystems and are thought to have been introduced in the ballast water of ships.

2) Extreme Opportunities: Whether it’s a flood or a hurricane, extreme climate events associated with climate change create disturbances that open up the opportunity for invasive species to move in and become established. Further stress, such as extreme drought, can also reduce native species or ecosystem resilience, increasing susceptibility to forest pests and secondary pathogens.

Example: Gloomy scale populations explode under warmer temperatures, and drought-stressed trees are more susceptible to this native pest than those under normal conditions

Figure 2: Gloomy scale infestation on maple (credit: Steven Frank, NCSU)

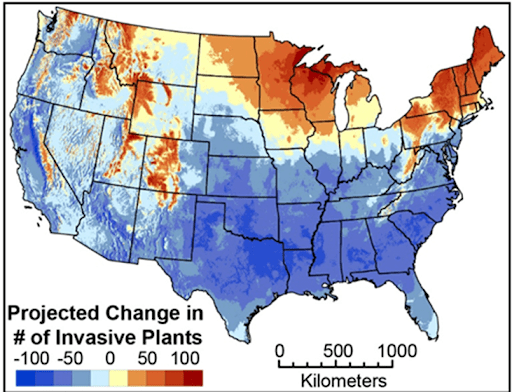

3) Some Like It Hot: A warming climate allows invaders to shift their ranges northward and into higher elevations, thus invading new previously uninhabitable ecosystems. Projections suggest that regions such as the Northeast are likely to see a greater number of “range shifting” invasives than any other region of the country.

Example: Nutria and water primrose are moving north as the waters warm

Figure 3: The Northeast and Midwest are projected to become hotspots for invasive plants in the next 50 years. Allen and Bradley, 2016.

4) Seasons of Change: With the shorter and milder winters resulting from climate change, invaders who were previously limited by long cold winters have been able to survive farther north and expand their populations. Additionally, many studies have documented invasive species that are able to shift their phenology more rapidly than native species to take the most advantage of an extended growing season by greening up earlier and staying green later.

Example: Highly destructive forest pests previously limited by cold temperatures, such as hemlock wooly adelgid, are able to survive winters farther north, leading to widespread loss of valued tree species beyond initial predictions.

Figure 4: Hemlock Woolly Adelgid

5) Competition at its Finest: Many invasive species can more easily adapt to and take advantage of warmer temperatures and higher CO₂ levels than their native counterparts, thus becoming champions in the competition for resources.

Example: Non-native brown trout are only able to outcompete the native brook trout in warmer water temperatures.

6) Resistance and persistence: Under warmer conditions with higher CO₂ levels, certain invasive plants may become less vulnerable to previously effective treatments. Herbicides may be less effective with higher atmospheric CO₂, as certain invasive weeds grow faster and are more resistant to herbicide under higher levels of carbon dioxide. Changing climates may also disrupt the effectiveness of biological control agents by creating a mismatch between previously synced phenology of the invader’s life stages.

Example: The invasive weed Canada thistle is resistant to herbicides under higher levels of CO₂

Figure 5: Differential efficacy of the herbicide glyphosate to control the aggressive perennial weed, Canada thistle, at ambient and future CO2 concentrations.

In addition to considering how climate change impacts invasive species, scientists are also exploring how invasive species are impacting the climate. Devastating tree loss due to invasive forest pests is now being considered as a loss of carbon storage potential and, therefore, a contribution to rising CO₂ levels.

Seeking Solutions

At a first glance, this double whammy could make us throw our hands up in despair. However, despite the formidable challenge that these compounding issues pose, scientists and diverse stakeholders are putting their heads together to seek solutions to the invasive species and climate change conundrum.

Based on the outcomes of a workshop with scientists, policymakers, and invasive species managers, Beaury et al. 2020 compiled a series of recommendations for addressing and curtailing some of the climate change and invasive issues, including:

- Strategic Planning to prioritize vulnerable areas, to plan for invasive species detection and management after extreme events, and to include invasive species in climate change adaptation plans.

- Preventive Management to plant climate-resilient native species while creating a watch list and keeping an eye out for range shifting invasive species.

- Treatment and Control can be adapted to shifts in growing seasons, incorporate resistance and diverse treatment methods, and include rapid response when range shifting species are detected.

- Education and Outreach are necessary to keep up to date on new information and tools to incorporate climate change into invasive species management. Also, share your knowledge and best practices with your colleagues, stakeholders, and researchers addressing this issue.

- Policy that considers climate change impacts on invasives can be proactive by including the regulation of future potential invasive range shifters and streamlining the process to include new species in these regulations. Also, we can consider and include invasive species issues in climate change policy and planning.

Learn More and Get Involved

To address the challenge of invasive species under a changing climate, the Northeast Regional Invasive Species and Climate Change (RISCC) Management Network was established in 2016 through a partnership with the University of Massachusetts, the USGS Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, and the NY Invasive Species Research Institute at Cornell University. Our network includes invasion scientists, climate scientists, natural resource managers, policymakers, stakeholders from diverse fields, and the broader public. Our mission is to reduce the compounding effects of invasive species and climate change by synthesizing relevant science, sharing the needs and knowledge of managers, building stronger scientist-manager communities, and conducting priority research. The information in this article was produced by the RISCC. We invite you to visit our website at risccnetwork.org for more information about climate change and invasive species, our events, and how to join our network.

About the Author

Carrie Brown-Lima is the Director of the NY Invasive Species Research Institute at Cornell University. In this role, she works closely with research scientists, state and federal agencies, the NY Invasive Species Council and Advisory Committee and regional managers and stakeholders to promote innovation and improve the scientific basis of invasive species management. Carrie has nearly 25 years of experience with natural resource conservation and management across ecosystems and borders. She spent more than a decade developing conservation strategies in Brazil and throughout Latin

America including programs such as sustainable fisheries certifications, agriculture and conservation, and transboundary protected areas.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.