by Dr. Randi Eckel

In the fragmented ecosystems where we live and work, the importance of diversity in our landscapes cannot be over emphasized. Diversity of native plants, insects, mammals, birds, amphibians…. They all play a crucial role in sustaining a healthy environment.

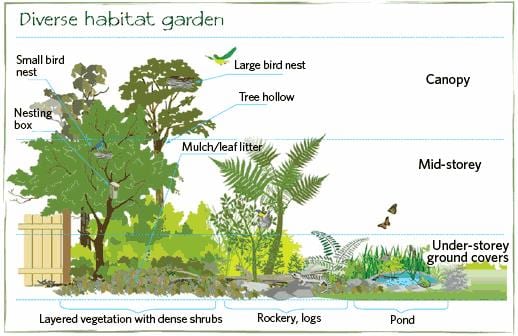

When we encourage a diversity of native plants in the landscape, we provide just one component of a successful habitat. We all learned the components of sustainable habitats when we were in elementary school – all creatures need food, shelter, and water. But what does this mean in a landscape? We need diversity of food: native plants that supply food for insects that in turn become food for other insects, birds, and animals large and small. We must have plant diversity to feed a diversity of creatures, but we also need structural diversity. Places for butterflies to hide at night and moths to hide during the day. Places for all sorts of creatures to shelter from weather, both summer and winter. Places for cover and nesting sites. We need diversity of form: trees, shrubs, evergreens, and groundcovers; leaf litter, brush piles, rock piles and fallen logs. We also need water – streams, ponds, bird baths, and mud puddles. Incorporating all these elements into the landscape does not require a large space, but it does require creative vision.

Ecologically balanced habitat gardens require food, shelter and water as well as a diversity of structure and native plants. Source: City of Ryde, Australia, http://www.ryde.nsw.gov.au)

By using native plants we are attempting to recreate functioning ecosystems. To do that, we need diversity! Yet we use only a tiny fraction of the plants at our disposal when we plant or enhance our gardens, fields, and forests. In doing so, we hamper the ability of those ecosystems to function well. The more plant diversity we employ, the greater diversity of insects we will have in that ecosystem.

Most insect herbivores (like caterpillars and beetles) are specialists – not generalists. If their host plant is not present, they will not be present either. We have learned this lesson very well from the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) – as we all know, they rely on milkweeds (Asclepias sp.) to feed their young. But for a successful ecosystem we need lots and lots of insects of many different types. Just as plants are critically important to the planet because they capture the energy of the sun, insects are the primary herbivores that begin the movement of that energy up the food chain. Plant choices will drive food choices which will dictate who, if anyone, lives in any ecosystem. By employing a greater diversity of native species in the landscape, so too, will we create a more diverse faunal component. More diverse butterflies, yes, but also more species of all sorts of arthropods (predators, parasites, etc.) as well as more species of birds, mammals, turtles, salamanders, and snakes.

An American painted lady caterpillar (Vanessa virginiensis) feeding on Sweet Everlasting (Pseudognaphalium obtusifolium).

For ecologically balanced habitat gardens to be accepted requires education. In a well-balanced habitat garden, herbivores stay in check due to the balance of predators and prey. Folks are, by and large, afraid of caterpillars and most other insects in their gardens – but they love butterflies and birds. The connection between hundreds of species of caterpillar turning into beautiful butterflies (and moths!) and also serving as a major food source for birds is not apparent to most people. The same is true for many other creatures that occupy the world around us. Toads eat slugs. Snakes eat mice and voles. Hawks eat rabbits. They may not all be pretty to the average eye, but they all work together. By creating an ecologically balanced habitat through the use of diverse native plants as well as structural diversity, a landscape can support an entire community of creatures.

Sadly, the average landscape project uses only a minute fraction of the native plants at our disposal. New England, for example, has approximately 2,500 native plant species (Atlas of the Flora of New England, Angelo & Boufford, http://neatlas.org/ ), yet your average landscape project uses only perhaps 20 of them. The same beautiful few are used over and over again: butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), New England aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae), and just a few others. But there are so many more native plants to embrace.

One reason for the use of the same plants on every project is, of course, that these are the plants that have been “discovered” by the horticultural industry and are easily available. This creates a vicious cycle, with businesses stocking only plants that customers ask for – and customers asking for the same plants that are always available. But another factor driving this lack of diversity is that through terrascaping and soil amendments, we attempt to turn all soil in gardens into “average to moist loamy soil with a neutral pH.” Shouldn’t we stop trying to change every inch of soil beneath our feet? Instead, we should embrace the soil types and moisture conditions we have and take advantage of the fantastic array of native plants adapted to particular conditions. Embrace the wet swale, the heavy clay, the rocky outcrop, and the sandy soil. We can use the great diversity of native plants to fill every niche, for there is truly, in the abundance of native plants at our fingertips, a plant for every place.

By using a diversity of native plants, we can encourage functioning plant communities that have few pest problems and beautifully support a vast array of wildlife, with herbivores and predators and parasites all balancing one another.

About the Author

Dr. Randi Eckel has been studying native plants for over 30 years, and founded the mail-order native plant nursery Toadshade Wildflower Farm in 1996 to further public awareness and availability of native plants. A life-long naturalist, lover of nature, and confirmed plant and ecology nerd, Randi specializes in the interactions between plants and other living things. She is known for her lively and engaging lectures and workshops on growing and propagating native plants, and offers interesting, nuanced information on the complex issues facing native plants and native plant communities.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement.Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.