By Uli Lorimer

Published by Timber Press

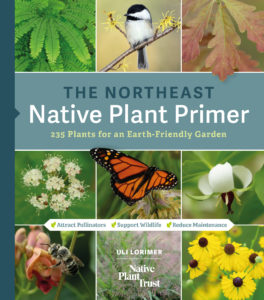

The following excerpt is adapted from Uli Lorimer’s book The Northeast Native Plant Primer (Timber Press Publishing, May 2012) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher and the author.

What Is a Native Plant?

What defines a native plant? This is a question of context and scale. At the continental scale, a Colorado blue spruce would be considered a native plant for Northeastern gardens. It is hardy here and will grow without too much fuss. But just because it can grow here does not mean that it naturally occurs here.

Trilliums and squirrel corn (Dicentra canadensis) welcome spring in Northeast woodlands.

Northeast native plants naturally grow within the Northeast and were present before European settlement began. They came to exist in our region by their own means or via introduction by indigenous people because of their use as food, fiber, medicine, or ritual. I would add another important dimension to the definition of native plants—namely, these plants have coevolved and are codependent with the insects, birds, and wildlife of our region. To create a garden that bursts with life, you must include the plants that these organisms need. So how do we define the Northeast region? The simplest answer is to list the states that traditionally make up the northeast—Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. However, from a plant’s perspective, the boundaries that define these states are arbitrary. The ranges and distributions of native plants are defined by a combination of geology, soils, hydrology, interactions with wildlife, disturbances, and plant succession.

A wet meadow at Nasami Farm is a showcase for color and diversity in summer.

The one unifying element woven through all of these definitions is change. During the last Ice Age, most of the Northeast was under a massive glacier. As the ice melted, plant communities moved back in. We know that indigenous people used and shaped the land for thousands of years, and we know that the ways in which the land was used have changed since European settlements began. Native plant communities have always adapted in response to these changes. Forests and woodlands were cleared for agriculture and later abandoned, enabling plant communities to shift again. This process continues today, with plants adapting to the disturbances of modern life.

Seaside Goldenrod is a favorite with pollinators.

We have also introduced nonnative, or exotic, plants from other parts of the world, some of which have become naturalized in the wild by reproducing without our help. These plants were brought here as food, medicine, and fiber, or as ornamental plants for our gardens. Unfortunately, some of these plants have established themselves in wildlands in our region. These nonnative, invasive plants—invasives for short—grow unchecked without natural predators or competition, resulting in displaced native plant species as well as any wildlife that relies upon them for food and shelter. Today, nearly one-third of the flora in our region is made up of nonnative plants, many of which came to the Northeast through ornamental garden nurseries, including oriental bittersweet, Japanese knotweed, and purple loosestrife, to name a few. Our activities as humans have profoundly altered the landscape on a grand scale; therefore, the choices we make in our gardens are important. It’s a great idea to remove any known invasives from your garden and replace them with native species.

Creating Biodiversity in Our Backyards

A good argument could be made for the statement, “No place on Earth is untouched by humans.” Some places may not be directly impacted by our presence, yet they certainly are influenced indirectly through climate change, pollution, and introduced species, which are all results of human activity. Furthermore, the concept of wilderness being separate from humans no longer stands up to scrutiny. We must envision a future in which wild creatures of all shapes and sizes are afforded space in our built environment. Gardens are, and need to become, habitats for animal life in addition to positive environments for humans; we are as much a part of nature as the bird, the bee, and the butterfly. All we need to do is meet the basic needs of ecological functions so that diverse life can flourish. Although creating habitats in our gardens may not be the perfect approach, it is one that we can influence for the better of the greater ecosystem.

Predators such as the crab spider have evolved close relationships with native plants, including coloration that enables them to hide while awaiting insect prey.

So what do you need to do to enact this vision of the future? Make your garden as diverse as possible, aim for at least 70 percent native plants, and avoid using harsh pesticides. These are great places to start. Your garden, just like Mother Nature, is layered and three dimensional, with plants covering the ground, perennials that return year after year, a shrub layer, and a tree canopy above. Within these layers exists a multitude of habitats for insects, fungi, reptiles, and birds to thrive. Throw in a source of water—as simple as a bird bath or basin or as expansive as a pond—and keep leaf litter and organic matter mostly in place, and you have created a garden that is also a habitat for wildlife.

Embracing wildlife in our gardens lifts our spirits.

As much as we strive for balance, there will be challenges. We are all aware of the deer pressure in the Northeast. There are few things more frustrating than going out to the garden only to discover your prized trilliums have been eaten to the ground by a marauding pack of hungry deer! Any diverse habitat will include pests alongside beneficial organisms; deer, rabbits, groundhogs, and insect infestations come with the territory. Thankfully, there are resources out there that you can turn to for help, including friends and neighbors, garden centers, nurseries, and county extension services. Keeping ecological function in mind can help you make conscientious, compassionate decisions about your garden pest problems.

Connecting the Dots

The power of photosynthesis has made plants the foundation of most terrestrial ecosystems on the planet. Plants convert sunlight into sugar, which eventually results in more plants. Plants then provide food, shelter, and habitat for insects, fungi, bacteria, reptiles, birds, and mammals. These relationships were forged long ago in the crucible of evolution and are the reason for life’s diversity.

A mere fraction of the wildlife supported by virgin’s bower (Clematis virginiana), a native perennial vine.

Plants and the organisms that eat them have long been involved in an arms race. Plants evolve defenses to avoid being eaten, and herbivores evolve resistance to those defenses. Over long periods of time, herbivores have developed what could be described as “dietary restrictions.” To survive, to breed successfully, they need to eat the right kinds of foods. When those foods are missing from the landscape, the plant-eaters diminish and disappear, creating a domino effect for omnivores and carnivores that rely on the herbivores for their sustenance. Native plants that evolved here in the Northeast come with all of the relationships with herbivores intact. Nonnatives and plants from other continents simply cannot provide as much for the herbivores because they are the wrong kinds of food.

Native species also support pollinators, both generalists that aren’t picky about which flowers they visit and specialists that need specific plants to fulfill their dietary requirements. Pollinators help plants achieve their goals of making seed and surviving for future generations. Native species support the caterpillars of butterflies and moths, which in turn provide food for songbirds and their fledglings. Those songbirds will mature and help the plants disperse their seeds, again to the benefit of the plants and for future insect herbivores and future songbirds. It makes perfect sense that gardens with at least 70 percent natives will host a greater number and diversity of insect herbivores and pollinators and will attract a greater diversity and number of birds, reptiles, and mammals that need those insects for food.

Harvestman on Clematis virginiana.

By connecting the dots, we can learn to celebrate the language of nature in our own gardens. Listen for the crescendos of a warbler’s song spilling over itself, the gentle chiding of the nuthatch, or the chirp, churr, buzz of grasshoppers,crickets, katydids, and locusts. This language is spoken in the knocking and creaking of tree branches in the breeze, the scratches and rustles of grasses in the wind, and the audible snap as a partridge pea seedpod pops open to eject its contents. Open your home to the wildness that lurks around its edges, and you will be surprised, delighted, and inspired by the creatures that make your garden their home.

About the Author

Uli Lorimer is the Director of Horticulture at the Native Plant Trust. Uli’s background in horticulture goes back to high school when he worked for local nurseries and noticed that every company was selling the same types of plants. That led him to seek out work with botanical gardens that specialize in growing and displaying plant species not found in most gardens. Thus began his fascination with plant diversity. His position as Director of Horticulture at Native Plant Trust is an ideal fit. Uli holds degrees in botany and horticulture from the University of Delaware, which led to positions with the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington D.C., Wave Hill in New York City, and the Brooklyn Botanic garden. During his 14 years with the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Uli broadened his native plant knowledge and fascination with where and how native species grow in the wild. Uli’s new book, The Northeast Native Plant Primer, provides a roadmap to help you include native plants in your garden, whether you are new to gardening or a seasoned professional.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.