Landscape Ecology

By Michael DeRosa

To design ecologically informed landscapes with more than just a collection of aesthetic elements, training in population ecology and wildlife biology is fundamental. Effective and sustaining landscapes are informed by the surrounding environment and are created by incorporating structural and species diversity into planting schemes to push minimalist restoration efforts to efficient results. Designed landscapes incorporate specific ecological principles into the design elements: topography, hydrology, sun exposure, species interactions, surrounding landscape elements, and edge. Landscapes can be designed and constructed that function well within the larger ecosystem immediately surrounding the site, thereby enhancing the function and value of those areas as well as the site itself.

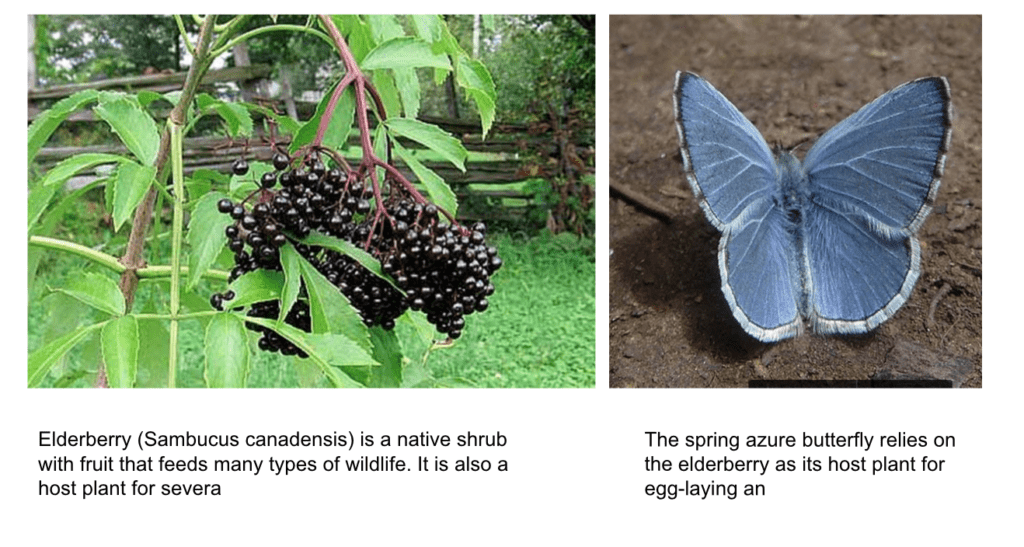

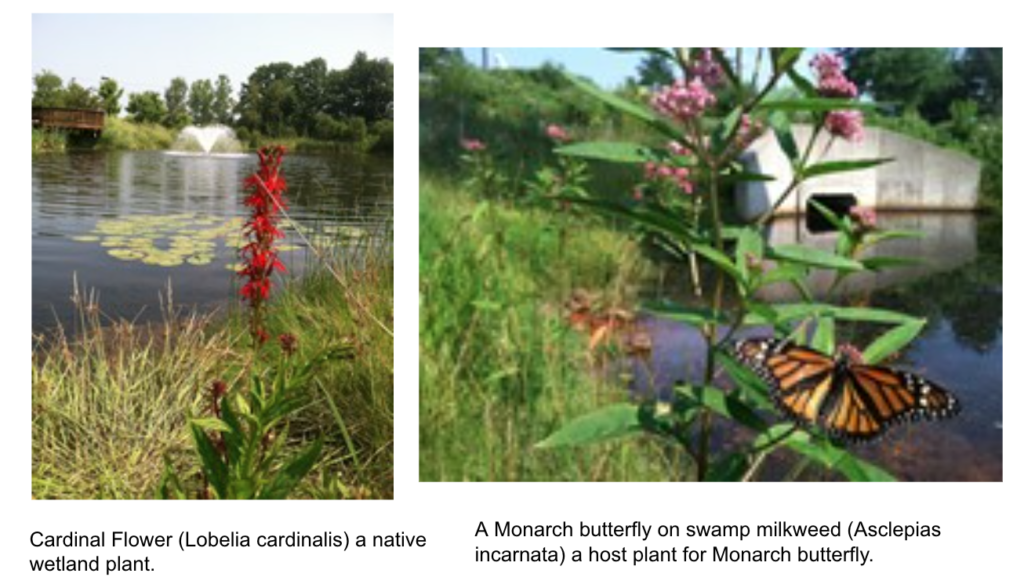

Design can be inspired by the surrounding landscapes and the knowledge of local ecological systems. Developing grading plans with the project engineer allows for an appropriate relationship with the water table, ensuring appropriate hydrologic conditions during the growing season. A successful design depends on this connection to the water table and the surrounding wetland area. It integrates with the adjacent landscape, creating a corridor for wildlife between the two habitats. Native and naturalized plantings work with the existing environment to form landscapes of interest and increase the function and value of wildlife habitat. The inclusion of various wildflowers in the upland areas, blooming during spring, summer, and fall seasons, provides aesthetic interest and can create an edge/ecotone that also improves wildlife habitat function and value.

A bluebird gathering caterpillars for its hungry brood relies on native plant and insect interactions to provide enough food to fledge all their chicks.

Invasive Species Management

We rarely work on sites that are not occupied by one or more invasive plant species. These plants have evolved in ways to reduce the health and vigor of surrounding native plants and are successful in colonizing areas and eventually dominating the local habitat. As a result, species diversity decreases along with ecological health and community stability. Japanese knotweed, for example, is a dominant invasive species at New England sites. Our strategy is to continually stress the plants with whole-plant removal, facilitated by mechanical strategies. Repeated removals force the plants to use energy reserves from the root mass with no new energy increase from the standing plant. Over time the roots expend all their stored energy in creating new stems and leaves that are continually removed. Our native plantings are then able to occupy the restored space unencumbered. Maintenance is always required but decreases significantly over time.

Wetland restoration within impaired and constrained sites requires creative and ecologically based solutions but can be efficiently managed with coordinated design strategies.

About the Author

Michael DeRosa is a Professional Wetland Scientist and population ecologist specializing in ecological restoration. He is a Licensed Site Professional and manages hazardous waste site evaluations, assessments, and remedial actions within the Commonwealth. Mike is also a LEED Accredited Professional under the US Green Building Council and consults on green building and LEED certification projects. Mike incorporated DeRosa Environmental Consulting, Inc. in 1994 and has developed the company into a diversified group of scientists that focuses on ecologically-based solutions to the day’s environmental problems. More recent collaborations with Northeastern University Marine Science Center and Halvorson Design Partnership/Tighe and Bond Studio have resulted in the construction of living shorelines and research and design of climate-resilient strategies within our coastal ecosystems.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.