by Robert Kourik

This slightly revised excerpt from Lazy-Ass Gardening (2019) is reprinted with the author’s permission.

You say you want to garden all-naturally, but the closest source of animal manure is many miles away? Then green manuring might be for you. Green manuring is the process of tilling fresh green plants into the soil to help make it drain better and allow it to hold onto more moisture, with an added bonus – the plants, as they decay, act as a readily available fertilizer. Green manuring is also pretty darn close to free fertilizer – discounting the cost of a few seeds and plenty of elbow grease (the truly indolent can always hire some elbows; or, you can simply cut the foliage off and take it to a compost heap and let the remaining roots do all the work – this is technically called “cover cropping.” Cover cropping takes longer than green manuring to improve the soil, but is much less work.

Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa) is one of several nitrogen-gathering legumes is one choice for green manure.

Green manuring is a valid way to care for the soil for a few years before jump-starting its improvement on the path to a no-till garden. Any old plant material, dead or alive, can help improve your soil. Eventually, any kind of organic matter will be fully decomposed and converted into humus – that most wonderful, stable, moisture-holding, nutrient-rich constituent of the soil. Humus plays an essential role in nutrient exchange, especially in an organic garden that’s untouched by chemically reduced fertilizers.

Learning how the natural cycle of decomposition works means you’ll know exactly what part of the cycle to influence, how to speed up the natural processes, and how to improve the soil in either the short or the long term

Dry or Juicy?

If your plant refuse is dead, dry, and straw-brown when it’s turned under, it will improve soil structure – but only over a long period of time. The soil bacteria that digest it need moisture, warmth, and nitrogen to increase their population levels high enough to decompose the raw material. If that raw material is dry and crusty, that means it’s also low in nitrogen and high in carbon, so it’ll take the bacteria a longer period of time to convert the higher percentage of carbon to a more decomposed, partially decayed form known generally as “organic matter.”

Because it takes many weeks, or even months, for the high carbon content of the dry organic matter to be converted into available nutrients, the nutrients won’t be of any value to a recently planted crop. In fact, incorporated dry material will probably rob nitrogen from the surrounding soil for a while.

Common theory has it that the loss of soil nitrogen that occurs with the drier stuff helps to build up the bacterial populations needed to decompose the more carbonaceous material. (One interesting theory, as discussed in the book Mineral Nutrition of Plants by J.B. Page and G.B. Bodman [the Wisconsin Press] postulates “that the commonly observed depression in plant growth immediately after adding large amounts of green manure…may be due to competition between the higher plants and microorganisms for the limited supply of oxygen than any other single factor.”) Either mechanism will often cause new crops to appear stunted, produce yellow leaves, and grow poorly. Using dead, dry and crusty plant matter to improve soil is like putting money into a long-term bank note; there are few immediate benefits, the long-term payback is good.

If the plant matter is turned into the soil when it’s fresh, green and, therefore higher in nitrogen, then the soil bacteria can easily and readily decompose its tissues. The premier virtues of green manure are that the plant matter is decomposed quickly, and that you can plant relatively soon after tilling it in. As a rule, the prudent gardener need only wait two to four weeks after tilling a green manure into the ground before transplanting or seeding. Green manure is more like playing the fast-moving stock market – the gains can be immediate and significant. To put the largest amount of green-manure fertilizer into your portfolio, however, you’ll need to know how to leverage all aspects of the green-manure cycle. (If you’re using taller and bulkier green-manure plants like fava beans and vetches, the foliage can be cut and hauled away to a compost heap to rot over time – very much less work than tilling.”

Green Manure – The High Fiber Diet

Because of its rapid decomposition, green manure is also a good way to add fiber to the soil. As the fiber decomposes into organic matter, it will help loosen heavy clay soils and assist sandy soils in retaining moisture. Since the plants are turned under when they’re fresh and green, the next crop planted there will also get a healthy boost of nitrogen.

The best green-manure plants for sheer bulk of fiber are the grasses and cereals. While these plants are growing, their very extensive and massively fibrous root systems help loosen clay soil by actual penetration and ramification of it.

“Free” Nitrogen with Good Timing

The optimal time to till under a green manure crop to provide maximum nitrogen for a subsequent crop is just as it begins to bloom. Yes, the conscientious green manure must ruthlessly “sacrifice” beautiful blossoms for the optimal amount of nitrogen.

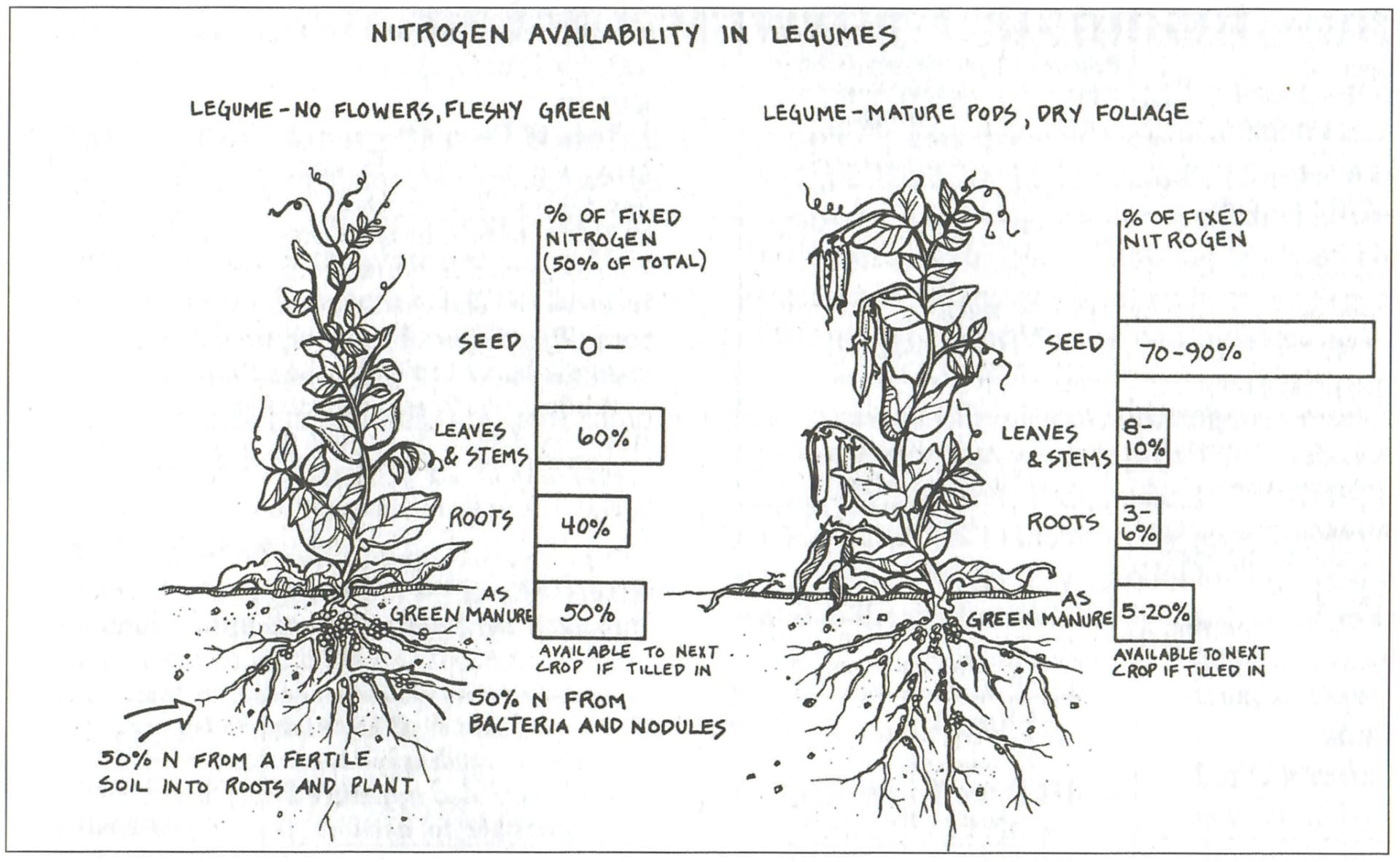

This drawing may look scary, but relax and read on. Basically, it’s a way to demonstrate a simple fact: to gt the most nitrogen out of a legume you need to till in or harvest the plant before it blooms. On the left we see that 60 percent of the nitrogen is tied up in the foliage and stems of a plant, so that the nitrogen can easily “dump” into the seeds when they start forming. (The seeds can contain up to 90 percent of the plant’s nitrogen, which is needed to form the protein in them.) When you till in or harvest a legume before it blooms, up to 50 percent of the fixed nitrogen is available to the next planting. If you wait until seeds form, only 5-20 percent of the nitrogen produced is available to the following planting.

A Balanced Regimen for Green Manuring

There’s no reason why you can’t have the best of both green-manuring worlds, using materials both dry and juicy. Like any good investment plan, a diversified portfolio is the wisest and safest strategy. While too much of a good thing can work against you, “moderation in all things” is a more beneficial approach with green manures. With grasses, cereals, non-leguminous plants, and legumes all blended together into one seeding, you’ll get a broader range of nutrients, root zones, and secondary benefits (such as weed suppression).

Perhaps one of the most classic green manure blends is a combination of oats (or ryegrass), vetch, bell beans and Austrian peas. This combo has a history that goes back hundreds of years in Europe. Some version of this blend of grasses and legumes has been the nutrient backbone for many a farm, and for much longer than chemical fertilizers have been around.

The percentages of each component vary from supplier to supplier. Peaceful Valley Farm Supply’s mix is composed of 49% bell beans, 20% Austrian field peas, 20% purple vetch, and 20% Oregon annual ryegrass. Gardeners steeped in the history of European gardening methods often add some oats to this mix to add the fibrous bulk of a cereal grass. Other gardeners figure their soil already has so much existing wild grass seed (mostly forms of ryegrass) that just adding a blend of legumes produces the same effect as the traditional European mix. Don’t forget, roots are working 24 hours a day, “cultivating” soils far deeper than even the most compulsive maniacal gardener could till.

Planting Your Green Manure

All green manures should get off to a good start with the same careful soil preparation that you would use for direct-seeded crops such as beans, corn and carrots. (Tossing green manure seeds out into rough or untilled soil is like throwing some of your valuable stock certifications into the wind.) As a general rule, seeds should be covered with a layer of soil equal to three times their diameter. Big seeds, such as bell beans, need only a rough seedbed, but finer seed, like ryegrass, does much better if the soil preparation more closely resembles that used to prepare for a bed of carrots or radishes.

Green Manures in the Grand Scheme of Things

Green manures, coupled with fallow periods and cover crops, are an integral part of crop rotations that range from four- to 27-year cycles (Yes, 26 years, measured by observation of traditional farmers sharing fields in Europe.) With a rotation of sufficient length to allow the soil to “rest” and accumulate nutrients, you can grow all your own fertilizer in place, without having to leave your yard to haul in smelly manure.

Nitrogen Gathered by Legumes (depending upon the type of legumes and the study)

| Common Name | Pounds per acre |

| Hairy vetch (Vicia villosa) | 80 |

| Dutch white closer (Trifolium repens) | 100 |

| Alsike clover (Trifolium hybridum) | 140 |

| Red closer (Trifolium pretense) | 140 |

| White sweet clover (Melilotus albus) | 160 |

| Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) | 250 |

About the Author

Robert Kourik learned various horticulture-related skills from the inside out by working with clients throughout California and the rest of the country for over 25 years. During that time he’s taken on design projects of all sizes, shapes and textures—water gardens, paths and patios, elegant arbors, habitat gardens, innovative home playgrounds, outdoor barbecue areas, deer-resistant gardens and landscapes, and low-profile and attractive deer fences, to name just a few. In the late 1970s, he wrote Designing and Maintaining Your Edible Garden – Naturally, which has become a classic in its field and helped to define the genera of gardening now known as edible landscaping. All of his books are available for purchase on his website: robertkourik.com.