by Jonathan Bates

After ten years of learning from and collaborating with a mega-diverse, globally inspired, edible forest garden, new wonders are under foot. Paradise Lot, here in Holyoke, Massachusetts, USA, has a soil story to tell, and we are finally getting around to deciphering its wonders.

Since 2004, each year we installed a portion of our design of perennial polycultures of multi-purpose plants into sheet mulched garden beds. Although we knew adding copious amounts of carbon and nitrogen rich materials onto the nutrient poor, lifeless ground, would one day “bear fruit,” we got real fruit and lots of it, along with fruit of another kind – humus.

Humus is the be-all and end-all of healthy soil. With aggregates formed by life, able to hold multiple times its weight in water, teeming with unfathomable organisms, and packed chock full of the minerals plants and animals need for growth, humus is what gives us powerful resilience in the garden.

With very little direction from us, life has taken the components we offered: compost, mulch, plants and water to turn a dead lot into a thriving edible ecosystem. Here are the results:

| Soil Conditions in 2004 | Soil Conditions in 2014 |

| Compacted clay and sand, no topsoil | 6 to 12 inches of new spongy topsoil |

| Opportunistic weeds like quackgrass, goldenrod | New introduced overgrowth is useful to the system: food, fodder, mulch, nursery stock |

| Organic Matter (OM) 2.4 % | OM 9 % (5 % humus) |

| Wide range pH 5.3 to 6.8 | pH 6.2 to 6.7 |

| Base Saturation ~ 86 % Ca / 7.5 % Mg | Base Saturation ~ 68.3 % Ca / 11.7 % Mg |

| Low to medium: NPK, calcium, magnesium, and trace minerals | “Almost perfect soil” — few mineral adjustments needed according to comprehensive soil audit |

| 3.5 cation exchange capacity | 11 cation exchange capacity |

| Partially polluted with lead | Lead soil is under mulch, healthy plants less likely to accumulate lead, lead bound to humus |

| Low diversity, soil smells like damp sand, or sulfurous clay | Dozens of worms in every shovel full of soil, soil smells like a forest |

From the beginning, the garden has chiefly been an experiment about growing tasty, geeky plants. Eric Toensmeier and I also hoped to answer the question, “Is it possible to grow food by mimicking a young temperate forest?” The answer is looking more and more like “yes!” Growing fruit was expected, creating a living soil – smelling, looking, and acting like forest soil – that’s an unforeseen surprise.

When starting your own edible forest garden or food forest, consider some of what we learned. Here’s a permaculture perspective on healthy soil:

- Start any planting project by doing a comprehensive soil audit. Bring someone in who knows about biological or nutrient dense farming, someone who can take soil samples, do the tests, and provide recommendations for improvement. There is a cost, but trust me it’s worth it. Northeast US resources include: forstersoilmanagement.com, www.bionutrient.org, and www.loganlabs.com. Or learn yourself how to assess the soils mineral needs by referring to a book: The Intelligent Gardener: Growing Nutrient Dense Food.

- Although university soil labs offer basic soil tests, I suggest staying away from them. Their tests are usually geared towards monoculture, conventional food production, and the data doesn’t account for the micronutrient complexities of no-till, ecologically rich soil. Labs like Logan Labs are accounting for soil nutrient balancing that the university labs don’t consider.

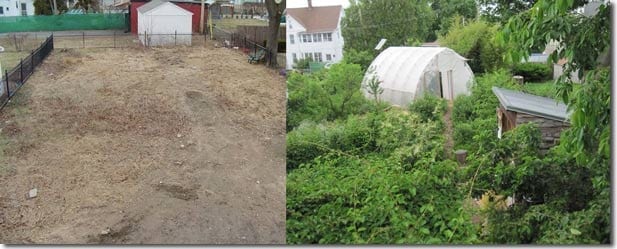

Backyard before and after shots, looking toward the back of the lot.As an example, gardeners are taught that a neutral garden pH (i.e. 7 on the pH scale) is best for growing plants. In fact, a pH of 6.4, in mineral balanced soil, has been shown to grow the best food. Some university labs are now testing for base saturation but usually leave out how to fix it (a base saturation of 68% calcium and 12% magnesium is best). They encourage a good organic matter content, but don’t necessarily tell you how to accomplish raising it to excellent (the percentage of humus is actually a better benchmark). Cation exchange capacity is tested by universities but not highlighted as important. High total cation exchange capacity means high biological activity and mineral availability

- Balanced minerals:testing labs will provide you with values for macronutrients as well as some of the more important trace elements. Many of the trace elements that aren’t tested can be balanced with a little broad spectrum foliar fertilizer (seaweed emulsion or liquid sea minerals) each year. The dozens of other trace minerals are taken care of by the soil. (It’s very hard to add them precisely, and they are used by plants at low amounts anyway).

- If and where there is need, build rain capturing swales and catchment areas. This is something we left out, yet should have included. Water can be a life enhancing force. Bring more into your garden for system stability, less irrigating from a fossil fuel powered chlorinated tap (in the city), all the while saving money and time. (If you have too much water, then build raised beds to get above it).

- Lift and aerate the soil as best you can before planting using a hand-powered broad fork or machine-driven keyline plow/chisel plow. Then add a mineral blend based on your soil test. Mulch over the native soil with compost and organic matter, then plant. Or at least grow a thick diverse cover crop over areas that will be planted later. There shouldn’t be a need to disturb the soil again after establishing your plant polycultures (perennials mean no-till).

- Good perennial plant diversity, designed to use the sun and root zone efficiently, seems to be key. Imagine what happens underground when dozens of species of plant roots, with their own unique biogeochemical mechanisms, pump life enhancing root exudates into the soil around them. I envision this enormous rhizosphere begetting an extremely vast soil food web, the cornerstone of healthy soil.

- Over the first two to five years (we retested at 10 years), you are striving for the highest percent humus you can, holding water in the soil, providing habitat for a high diversity of soil food web organisms, particularly worms and mycorrhizae. Mycorrhizae are the nutrient and moisture accumulators of a forest garden. The more you have, the more resilient the system will be.

- Bring animals into the system any way you can. They help with organic matter and nutrient cycling (saving labor, while producing a yield like eggs or meat). If the animals can’t be in the garden, bring the garden to them by cutting and carrying the weeds and chopped overgrowth to their pen. The resulting composted weeds and manure can be removed from the pen and added to beds at a later date. The woody prunings can be chopped up and added to the planting beds to feed mushrooms.

- Once your soil minerals are balanced and in the excellent range, your plants are thriving, pests and diseases are low, and you can’t keep up with the abundant nutrient dense harvests, consider the garden’s long term mineral balance. If you eat from the garden, it makes sense to return your poo and pee, and the nutrients that would otherwise be flushed away, back to the garden.

- We found that it is important to incorporate copious amounts of human engagement throughout the life of the project, particularly during the first years as we are aerating and mulching (planting, weeding and harvesting later on). We all get a workout, have fun learning and doing, and create important relationships for strong local networks (organize a permablitz in your own yard).

References

Some resources to check out regarding balancing and building soil in gardens and farms:

Jeff Lowenfels two books: Teaming with Microbes and Teaming with Nutrients

Steve Solomon’s book: The Intelligent Gardener: Growing Nutrient Dense Food

Any of the editor’s picks at Acres USA

The Amazing Carbon website: http://www.amazingcarbon.com/

Soil Foodweb Inc: http://www.soilfoodweb.com/

The resources recommended by Dan Kittredge at bionutrient.orgAbout the Author

Jonathan Bates has been learning about, thinking about, and teaching ecological design for two decades. He has helped create dozens of thriving farms and gardens in the Connecticut River Valley and beyond. He is the co-designer of his internationally recognized home garden and a contributing author of the award winning book about that garden: Paradise Lot: Two Plant Geeks, One-Tenth of an Acre, and the Making of an Edible Garden Oasis in the City. Additionally, he is a landscape design coach for his business Food Forest Farm.