by Heather Heimarck

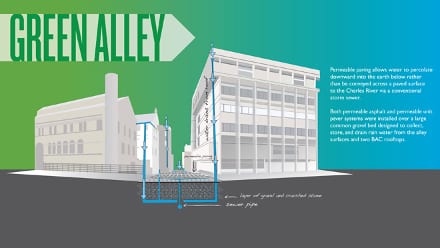

Boston Architectural College’s “Green Alley” was built with the intention of creating a replicable model that would ameliorate negative environmental impacts caused by urban streets and high building density. Cities lack porous surfaces to return stormwater into the ground due to road, rooftops and sidewalks built with non-absorptive or impervious surfaces. The high ratio of impervious surfaces contributes to stormwater flooding, increased pollutants washing into water runoff, as well as increased thermal absorption, the heat sink effect.

Beneath the streets and buildings lies the water table, valuable not only as a resource, but as a contributor to the stability of building foundations particularly those built on piles. Should the water table drop below normal seasonal variations for sustained periods of new lows, buildings supported on piles will be vulnerable to movement and structural stresses. The historic character and scale of Boston’s urban fabric is in part a reflection of the soils, the fill, and the water table beneath the city dictating appropriate construction techniques and loads.

The Boston Architectural College (BAC) approved a Climate Action Plan in 2012 committing the college to work toward a net zero campus. The Green Alley is an important early phase in this effort that included the installation of eight geothermal wells for heating and cooling the main building (to be connected in a later phase), stormwater management, bike racks, and a green vine wall. The Green Alley (Alley #444) runs mid-block, east and west between two of the major campus buildings, a fire station, a restaurant, and retail businesses on a block in Boston Back Bay defined by Newbury Street, Massachusetts Avenue, Boylston Street, and Hereford Avenue. The design team included landscape architects, Halvorson Design Partnership and civil engineers, Nitsch Engineering. The porous paving and underdrainage was installed by Valleycrest Landscape Development.

Breaking New Ground

As the first public alley project of this type, permitting and construction was complicated by the nontraditional approaches and confined project area. The project was delayed six months due to discovery of unknown obstacles beneath the surface and because the city mandated a moratorium on excavations in winter months. An urban project has many constituencies with concerns. In this case, not only adjacent neighbors had to be consulted but also a number of state agencies, including a state archeologist who assured that no artifacts such as Native American fishing weirs similar to those found at Copley Station would be destroyed. Thankfully none were found. Ultimately, the geothermal wells reached a depth of 1,500 feet before adequate conditions were found.

Construction is underway in the BAC “Green Alley,” also known as Public Alley #444. Photo courtesy of BAC.

The College celebrated the Alley’s completion with a ribbon cutting on October 18th, 2013, kicking off the BAC’s 125th anniversary year. Congressman Michael Capuano quipped in his welcome that it was a first ribbon cutting that he attended to celebrate the opening of an alley. Indeed it will not be his last as higher performance expectations are placed on the services provided by the Back Bay and neighborhood alleys. Just over a year after the BAC celebrated completion of the Green Alley, The Charles River Watershed Association “Blue Cities Initiative” celebrated the opening of Public Alley 543 in the South End, another porous alley, on November 21, 2014.

The Green Alley incorporates various permeable surfaces and caps several geothermal wells located beneath the street. Photo courtesy of BAC.

Function & Materials

The BAC Green Alley is used by all of its adjacent neighbors including the fire department for deliveries, storage, and limited parking. These neighbors cooperated during construction by receiving their deliveries at the front of their businesses; the BAC provided trash dumpsters on Newbury Street and parking when all had to be discontinued in the alley. As a part of the construction cost, the BAC provided for abutters’ parking in a garage while well drilling and excavations were underway, adding $300,000 to the project cost.

Since the Green Alley’s completion in the fall of 2012, out of the total 234,674 gallons of rainfall that has reached the site, only 97 gallons have flowed into the storm drain. This translates to an impressive 99% return of the stormwater to the water table. The material palette for the overall project was simple but effective and included:

- Porous paving – The center drive lane of the alley is porous paving, an open grain mix of asphalt which has traditionally been used by highway departments on super elevated roadway curves, to reduce skidding in wet weather. Porous paving or “popcorn asphalt” has been adopted by the design and construction community as a way to accommodate vehicles and porosity. While the paving industry recommends annual vacuuming of the surface to the keep the pores open, it has yet to be studied whether or not surfaces have to be vacuumed or the frequency. The BAC plans on vacuuming annually. Porous paving and the associated base have the added benefit of filtering out some of the harmful particulates and pollutants from the stormwater, thus improving the water quality of the stormwater.

- Permeable paving – Unit pavers, concrete pavers, cobbles, etc. supply varying degrees of porosity through the width of the joint separation between units or the flow through the block itself. Porous pavers were dry laid on a permeable bed to create the pedestrian zones and low traffic zones in the alley. The green alley is built with concrete pavers. The light color of the selected pavers has a high albedo rate, helping to reflect thermal heat thus mitigating the heat sink effect.

- Stormwater detention structural base material – The structural base material for both the unit pavers and the asphalt consists of (starting at subgrade) filter fabric, 36” bed of ¾ crushed stone, a second layer of filter fabric, 12” layer of bank run gravel, 1” sand bed. This base creates a stormwater detention area that the building downspouts are tied into and includes a safety overflow connection to the traditional stormwater system.

- Green Screen – The green vine wall is located on the South face of the BAC building, 951 Boylston Street. The attractive metal grid screen is mounted six inches from the face of the building and planted with both an anchoring vine and twining vine to insure strong coverage in a three year period as promised to approving agencies.

- Geothermal wells – Eight geothermal wells, 1,500 feet deep each, are located in the green alley and under portions of Hereford Street.

Conclusion

According to Ted Landsmark, President Emeritus of the BAC, “The Boston Architectural College’s Green Alley project demonstrates the College’s commitment to the immediate and long-term environmental challenges facing the City of Boston and our Back Bay neighborhood. The success of this project extends beyond the intelligent beautification of a single area of our campus to a replicable design with potentially far-reaching effects and includes the successful conclusion of the first phase of our geothermal system.”

The design of the alley seeks to accommodate vehicles and back-of-house services, as well as to unify and beautify the area. Invisible to the eye are the geothermal wells and the reduction of negative environmental impacts. To share the performance statistics of the green alley with the public, the BAC provides a link on the schools website to the monitor system. Fortunately, our environmental efforts have not gone unnoticed.

Sciencetogo.org’s ostrich mascot recognized the environmental benefits of the BAC green alley project.

The green alley has been recognized by sciencetogo.org, one of many groups working to engage the public on environmental issues. Sciencetogo.org is a collaborative project between UMass Lowell, UMass Boston, Hofstra University, the Museum of Science, the MBTA and the City of Boston. The project’s mascot, an ostrich, both promotes green innovations, “greenovations.” and offers a subtle call to pull our heads out of the sand. This past summer BAC was pleased to be one of the ostrich sites. The Ostrich marquee had interpretative signage that celebrated the stormwater and temperature successes of the BAC’s green alley and greenovation.

Resources

For more about the Science To Go Exhibit: http://the-bac.edu/experience-the-bac/news-and-events/news/sciencetogo-ostrich-news

For a video of the geothermal drilling project: http://the-bac.edu/experience-the-bac/videos/geothermal-drilling-video

For additional photos and diagrams http://the-bac.edu/experience-the-bac/galleries/geothermal-drilling-gallery

About the Author

Heather Heimarck, ASLA, MLA, is Director of The Landscape Institute at the Boston Architectural College. Her professional work spans from large scale urban planning projects such as the Lower Charles River Basin to campus and institutional work such as the award winning Honan Allston Public Library, streetscapes, bike lanes, and residential design. Heather received a MLA from the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University; she may be reached at heather.heimarck@the-bac.edu.