By Joshua Bruckner

Learning to Identify Spotted Lanternfly

Spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula, “SLF”) is an emerging invasive insect of concern in New England. With over 70 host plants, including the tree of heaven, maple, black walnut, willow, grapes, and hops, this invasive species can cause serious economic and environmental damage. Agriculture, forestry, timber, and nursery and landscaping industries all stand to be affected by this pest, so it is important to learn to identify SLF and report any potential sightings.

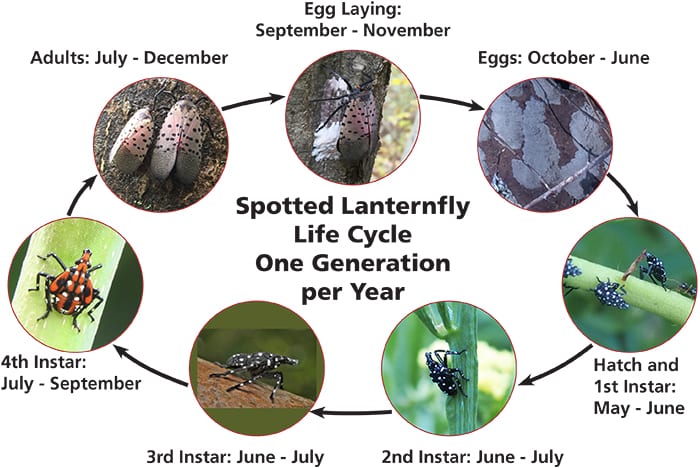

The life cycle of the spotted lanternfly. Diagram by NYS IPM)

Spotted lanternfly has only one generation per year, with adults dying off with the first hard frost. Eggs survive over winter and begin hatching in late spring, making now an important time to check for both egg masses and early instar nymphs. Female spotted lanternflies will lay eggs on nearly any flat surface, which makes the egg masses a challenge to survey for(remove comma) and means there is a big risk of them being accidentally introduced into Massachusetts on vehicles or on goods imported from infested states including nursery stock. Nymphs are small, especially in their early stages, and are excellent hitchhikers meaning they can also easily hitchhike to new locations. Landscapers and other outdoor workers are a first line of defense against the introduction of spotted lanternfly, so use the tips below to learn what their egg masses and nymphs look like and report anything suspicious you find this spring.

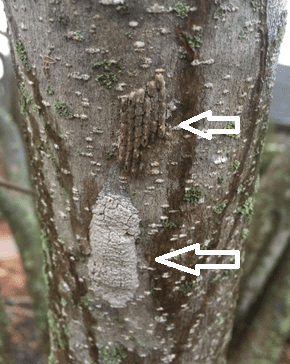

Spotted lanternfly egg masses, covered (bottom) and uncovered (top). Photo credit Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture

SLF egg masses have been found on some unusual items, not just trees, as these photos from Pennsylvania show:

Female spotted lanternflies lay one or two egg masses with about 30 to 50 eggs in each mass. The masses are usually covered in a protective coating that looks like a waxy putty, starting out white when fresh and later drying to resemble a gray, cracked, patch of mud. This rough gray surface works well as camouflage on many surfaces including tree bark, rocks and weathered wood. Exposed or uncovered eggs resemble strings of connected seeds.

The easiest things to confuse with SLF egg masses would be the egg masses of the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar). Gypsy moth egg masses can be found from late August until May on almost any vertical surface. They can be distinguished from SLF egg masses by their buff or yellowish fuzzy coating, and often have tiny pinprick holes on the surface, evidence of parasitic wasp activity. The eggs themselves, which can be seen by scraping away the fuzzy covering, are small and spherical, compared to the larger and more oval eggs of lanternflies.

(SLF egg mass on the left, next to a gypsy moth egg mass. Photo credit Emelie Swackhamer with Penn State Extension

Nymphs begin to hatch in late May or early June in Massachusetts but have already hatched in warmer southern states as of late April, meaning they could already be on the move to northern states. They go through four different instars, or stages, before transitioning into the adult stage which is evident in the fall. Early instar nymphs are black with white spots. Each instar is larger than the previous one, and the last (fourth) instar becomes a striking red color with black and white spots.

A first instar nymph. They are very small when they first hatch, just a few millimeters long. Photo credit Gregory Hoover

Like adult SLFs, nymphs have a proboscis they use to suck the sap from plants, but their smaller mouthparts mean they cannot pierce bark or woody parts of plants. Instead, they attack soft, succulent hosts such as the leaves and smaller stems of larger woody plants. While SLF has many host plants, nymphs can commonly be found on garden plants and herbs, particularly rose, basil, blueberry and cucumbers. The nymphs are much less discerning when it comes to host plants than adults, who prefer the tree of heaven. Be sure you check throughout the garden and pay special attention to the leaves of major host trees such as the tree of heaven, maple, and black walnut. Similar to adults, nymphs tend to swarm feeding sites in large numbers.

Early instar SLF nymphs feeding on a honeysuckle bush. Photo by Kurt Bresswein.

A fourth instar SLF nymph, with its distinct red coloration. Photo credit Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture.

Spotted lanternfly feeding does not lead directly to plant death, so their presence does not mean that your garden and backyard will be completely wiped out. However, this feeding can significantly weaken plants. These insects also excrete honeydew (similar to aphids), a sticky waste product that leads to the growth of sooty mold and can attract nuisance insects that feed on it. Oozing sap on host trees or suspicious buildup of sooty mold are both possible signs of an SLF infestation, so be sure to check for insects if you notice these signs or any other types of damage.

If you think you have found a spotted lanternfly nymph or egg mass, please photograph what you see and report it here. If you are not able to take a photograph, you can use a plastic ID card from MDAR (order some for free here) or a credit card to scrape egg masses off, place them in a bag or other sealable container and add rubbing alcohol as soon as you can – this will kill the eggs. Collect any nymphs you find using a jar or plastic bag and store them in rubbing alcohol or place them in the freezer. This process will ensure any specimens are well-preserved in case MDAR needs to collect the specimen after assessing your report.

Spotted lanternfly ID cards, which you can order for free.

To learn more about the spotted lanternfly, start with the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR)’s online fact sheet, where you can download several useful documents or watch one of our recent presentations on SLF. If you work in the green industry, download our Best Management Practices for Nurseries and Landscapers. Order your free spotted lanternfly ID card here.

If you live in a state outside Massachusetts and come across what might be spotted lanternfly, you should report it to your state’s department of agriculture. Searching for “spotted lanternfly” on the agency website will often bring you to any relevant information or reporting forms they have.

About the Author

Joshua Bruckner is the forest pest outreach coordinator at the Mass. Dept. of Agricultural Resources. He has a master’s degree in environmental science from Clark University.

Feature Image: Spotted Lanterflies on a Red Maple. Photo by Rkillcrazy Wikimedia Commons.

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.