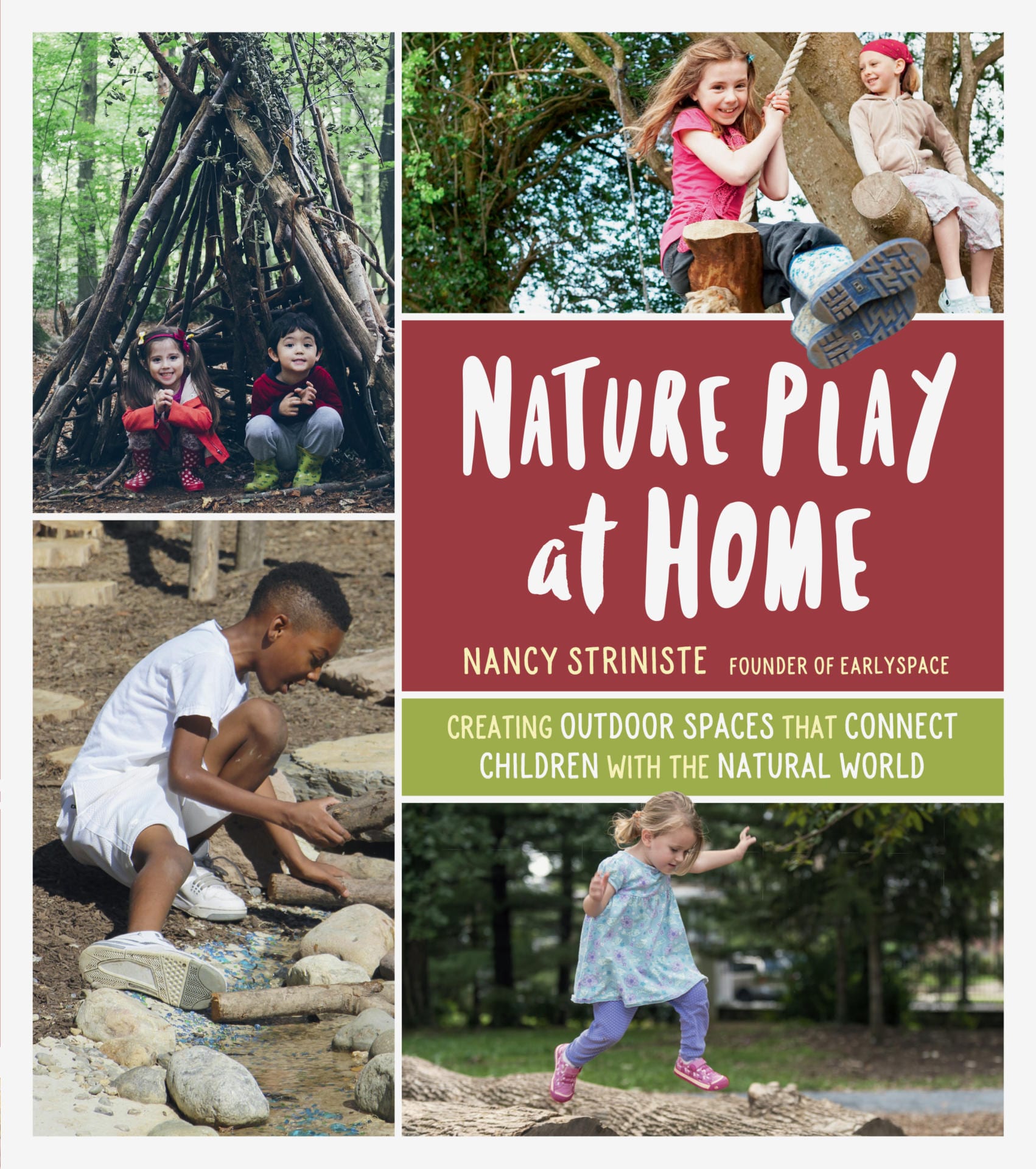

by Nancy Striniste

This excerpt from Nature Play at Home (2019) is reprinted with the permission of the author and Timber Press.

Spaces speak, especially to children. Just as the soaring ceiling of a cathedral inspires a sense of awe or a candlelit restaurant prompts us to lower our voices, the formality, informality, size, or openness of a space can tell us how to behave. As we create spaces for nature play, it is our responsibility to be mindful and intentional about the messages the space will transmit to children. Spaces for children can be organized and designed to honor and communicate respect for them. What’s needed is to build with an understanding of a child’s development—and with joy and a sense of fun.

Entryways

Creating an enticing, child-oriented entry is our opportunity to invite children into a natural play space, by indicating to them that the area they are about to enter is special. We want the entry to say “this is a place for you” and “come in, there are good, interesting things happening here.” To create an enchanting main entry, it is important to think about the experience of entering the space and make it more than just the functional step of transitioning from one area to another. Details are important. An entryway is an opportunity to add beauty, sound, invitations to touch something tactile or intriguingly shaped, and perhaps an element of mystery. Above all, the entryway should help the child feel like he or she has arrived home—to nature—in the deepest sense.

Entries that take the form of an archway will create the sense of arrival and transitioning from out to in, from there to here. An arbor adds ceremony to the experience. It can be planted with vines that soften the entry and allow one to pass through a wall of greenery. It can also be embellished with moving parts that spin or chime or invite touching. An arch can be small or it can be elongated so that one passes through something like a tunnel to enter the space. There can be one wide arch, or more than one. It is especially respectful to think about scale. Making the entry, or a portion of it, scaled to a child’s proportions gives little ones a sense that they were expected and that this place is for them. Having only a child-sized entry that requires adults to crouch down gives children a sense of ownership and says that grownups are guests in the space.

Playful cutout shapes along the top of a simple picket fence gate at the Coastal Maine Botanical Garden announce that fruit is growing nearby.

A beautiful gate—perhaps painted a vibrant color, or with added texture or sculptural embellishments—is another way to mark the experience of entering. Chimes, vines, pickets to run a hand or stick along, spinning pinwheels, weather vanes, whirligigs, fluttering flags, and peek-through holes all bring a fanciful element to the space around an entry and will entice children to engage with the space.

It is important to consider the views, the sounds, and the textures underfoot as part of the whole experience of arriving. Whether the view opens to a panorama or disappears temptingly around a curve in the path helps determine how the space will be perceived. Views can entice, reassure, and assuage fears. Youngsters arriving at school or childcare, or any new or busy place, can use a view into the space and the activity there to understand what to expect. Providing a place to pause, perhaps a bench at the entry, allows one to observe, orient oneself, and enter when ready.

The entry to my own garden is designed as a sequence of layers, moving progressively from open and public to sheltered and private. The outer layer, a stone wall against the public sidewalk, is planted with child-friendly lamb’s ears, lemon balm, and mint, along with flowers and grasses. These plants welcome strolling children and adults with fragrance, color, texture, and an invitation to pick some herbs. Perched atop the low stone wall is a tongue drum with a sign that says “play,” inviting passersby to pause, interact, and send some beautiful sounds wafting through the neighborhood. Up a few steps from the street is my house. One passes through a gate topped with a tiny metal bird sculpture and under an arbor planted with vines to enter the private front garden, which is filled with flowers, fragrance, and the sound of water overflowing a stone bowl fountain into a bed of smooth rocks.

A stepping-stone path leads through the garden and around the house, but the main brick walk leads up a few more steps and onto the porch, a sheltered transition space that connects indoors to out. It is a space where as a family, or with our friends, we can sit and visit, eat, read, or watch the birds, the rain, or life on the street—all from a protected perch. A carefully conceived entry can bring magic to a whole family’s day.

An arbor over a corner entrance to the yard extends the sense of arrival and leads to a little front garden sanctuary laden with flowers, fragrance, and art—such as a metal sculpture of a singing bird—and the sound of a burbling fountain.

I believe that such invitations demonstrate caring and create a sense of community. Take a cue from the Little Free Library boxes that dot neighborhoods across the country and think about ways to incorporate similar nature-inspired invitations to people walking down your own street. Sharing small moments sends an important message to and about your community. A swing hung from a tree close to the curb, a poem about nature posted near a sidewalk, a fairy house with invitations to arrange and interact: all of these convey a sense of welcome and friendliness, especially when natural materials are used.

More and more schools and parks are creating natural playscapes, and you can adapt things you see in these public spaces for your own home yard or neighborhood pocket park. For example, the entrance to Creative Minds International Public Charter School in Washington, DC, is marked with a covered pergola. Just inside the entry arch is a circular area with two rustic benches that serve as gathering spaces for transitions. This circle provides a site where children can pause, orient, and prepare for what is to come. It also encourages children, teachers, and parents to gather and chat right at the entry. Completing the space is a carved chameleon (the school’s mascot), an endearing welcome.

Entry areas can tell arrivals something about who made the space and what it is intended for. At Drew Model Elementary School in Arlington, Virginia, the entry path into its Reading Garden is the Word Walk, a concrete path with language arts terms pressed into the paving. This element is meant to welcome visitors and add texture and interest to the ground beneath their feet, while presenting curriculum in an unconventional and engaging way. Teachers provided lists of favorite literary terms and the walk became a uniquely physical way for children to connect to the words. You could adapt this at home by pressing a new concrete path with words meaningful to your family, names of family members, or even names of trees and plants in your yard.

Families can press leaves, names, birthdates, or favorite quotes into concrete to personalize pathways through a yard. Wet concrete is an almost irresistible invitation to children.

Paths

Circulation refers to the ways people travel through a given space, a key element of how well any space works. Paths—their width and materials, where they lead—tell children a lot about how to move through an outdoor space. Wide-open pathways tell kids that this is a place where they can move quickly and in big, exuberant groups. A narrow stepping-stone path says this is a place to move more slowly and carefully and probably single file. Thoughtful planning can provide important cognitive and motor experiences for children.

The very existence of a path tells us that we are following where others have gone before and there is comfort in that knowledge. Paths can include a view that will draw children along to an engaging play element. Serpentine paths can be mysterious and spur curiosity about what might be around the next bend.

Pathways, stepping stones, bridges, and tunnels transport us on our journeys, adding a sense of adventure. A good path helps us read the space and can clarify the way through. For both large and small spaces, details in the surfacing, the shape of the path, the terrain, and the landmarks along the way make the route memorable and help us to form mental maps. This in turn allows us to picture the space when we aren’t there, describe it to others, and find our way next time. Shortcuts, secondary spurs, and loops can be narrower than the main path and made of different materials. These might lead to unique destinations—a hidden boulder or a special view. Or they might just be an interesting side trip off the main path. The opportunity to make choices gives children a sense of control, and offering a selection of routes through the space empowers children. Paths should always lead somewhere, and loops are best for avoiding traffic jams.

It is important to think about the sensory experiences children have as they travel along paths. Surfacing with different textures can change the way pathways are experienced. The crunch of stone dust or pea gravel, the hollow clomp of a boardwalk, the rustle of walking on dry leaves, and the silence of a mulch path all feel and sound very different, deeply affecting our experience of a space. When we are alone or walking quietly, sound can add a meditative quality, helping us to be in the moment and notice each footstep.

The openness underneath makes walking on a bridge feel and sound hollow—very different from solid ground. Children notice this!

Paths can be direct and efficient or meandering and leisurely. Thoughtfully designed walkways can impact behavior in certain parts of the space and reduce the need for rules or repetitive verbal reminders. A clear path across a flower bed can lead a child through without blossoms being crushed. A route through a rain garden can allow immersion in the space without small feet compacting vulnerable soil. In these ways, paths can safely bring children close to nature without risking harm to what is delicate.

If you’re making paths out of concrete (which is a good way to ensure accessibility for all), remember that this material also provides an opportunity for creativity. Concrete should never be just a smooth (boring) surface. Press plant parts—leaves, ferns, flowers—into the wet mix to make beautiful fossil-like impressions when the concrete dries and the organic matter scuffs away.

Pathways can incorporate a variety of textures that will make walking, running, and riding more interesting and require us to be attentive. Natural stone, whether cut into precise squares and rectangles or broken into irregular shapes, will be long lasting and beautiful. Tree cookies in different diameters can be a ground-level path, or, if varying thicknesses and heights are used, can add a balance challenge to the route.

River rock and pavers set in a concrete path designed for barefoot walking create a unique tactile experience.

Children can make stepping stones out of concrete and embellish them with tile, marbles, shells, and stones to add color and texture. Planting scented herbs between steppers allows fragrance to be released as a child walks along the path—adding another sensory dimension to movement through the space. Plants can be neat and obedient with clear edges, or they can spill into the pathway at different heights, brushing against our legs or creating leafy curtains to push through.

Studies tell us that many of today’s children are less physically competent than children of the past. This is happening in other countries as well as the United States. In Germany, recent accident statistics showed increasing numbers of adults were being injured by falls while walking. In Germany, unlike in the United States, insurance is provided by the government, which influences their view of risk and litigation. The national health insurer approached the agency that designs play spaces and requested that more uneven surfaces be included in children’s spaces so that young people would learn to move more attentively, develop better balance, and reduce the number of costly injuries when they reached adulthood! To make your pathways engaging and challenging, think about including a mix of cobblestones, bricks, flat pavers, flagstone, river rocks, tree cookies, and timbers. Even simple treatments to paths can encourage children to move creatively through an outdoor space.

About the Author

Nancy Striniste is the founder and principal designer at EarlySpace, LLC. She has a background as both a landscape designer and an early childhood educator. She teaches at Antioch New England University in their Nature-based Early Childhood graduate certificate program and serves on the leadership team of NoVA Outside. Nancy’s goal is to bring nature to the places where children spend their time: backyards, schoolyards, churchyards, parks, and early childhood settings. She has worked with families, schools, childcare centers, municipalities, and organizations to create sustainably designed natural play and learning spaces and to teach about how to use the outdoors for learning and play.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.