by Katherine Sargent Cairoli, MA, LEED

An earlier version of this article originally appeared on OffCite, a blog published by the Rice Design Alliance, a community engagement organization based at Rice University.

Not all vacant lots are the same. Some are nestled between residential lots and looked after by neighbors; some are littered and adjacent to highways; still others have a nascent appeal that can benefit from the right intervention.

One such lot is located along Fulton Street between Panama Street and Hammock Street in the Near Northside. The property consists of two vacant lots owned by the City of Houston’s Parks and Recreation Department. A crosswalk connects the property to a light rail stop. There are commercial properties along Fulton to the north, south, and west; to the east is a residential area. Currently, there is one tree in the middle of the site, overgrown brambles and a row of trees along the fence on the eastern side of the property, and a utility right-of-way with power lines that bisect the lot.

The site is an empty lot on Fulton St between Panama St and Hammock St, across from a METRO light rail stop.

Community members have long wanted to create a pocket park here. Recently, they worked with the Greater Northside Management District (GNMD) to realize that vision.

Envisioning a Park

Rose Toro, a local artist who has done numerous installations in public spaces in Houston and other cities, got involved. She developed a concept for a butterfly garden to accompany a large butterfly sculpture that she will create. She then worked with the GNMD and Avenue CDC to secure grant funding for the initial phase of the project.

The GNMD needed more community input and a way to turn this concept into architectural drawings. They reached out to us at Open Architecture Houston (OAH), a local nonprofit that connects underserved communities with design professionals, to help facilitate the design and community engagement process.

The first community meeting solicited feedback from the community and allowed the OAH team to decide which design would be pushed forward to the final design phase.

First, we hosted a community design charrette with the help of partners Avenue CDC and GNMD, which included community members and volunteer design professionals. There, we presented the project scope and criteria specified by the community. GNMD had some additional criteria as well, as they will be responsible for maintenance of the park. There were to be no water features and no benches, but the community members wanted shade, bike racks, irrigation for plants, lighting, and signage. Community members and designers then formed groups and sat down together with maps, tracing paper, and markers to begin brainstorming possible uses for the lot — envisioning all the ways they could activate the lot and enhance their community. At the end of the evening, each group presented its ideas and shared its excitement about the project.

Making Refinements

Once all the sketches were compiled and ideas catalogued, the design work began. We had a follow-up meeting after the charrette where we divided the designers and community members into two teams to pursue two different concepts that emerged at the charrette. DeMera Ollinger led a team that included Allison Pate, Ishraq Aljassar, Tuyet Huynh, and community member Edward Carranco. Jaime Pujol led another team that included Lauren Norton, Blake Coleman, Katherine Gullick, and community members Lionardo Matamores and Mat Wolff.

The teams met for an internal OAH meeting to present and critique each other’s designs in preparation for the first community meeting.

The teams had three weeks to work on the designs before presenting them at a public meeting back in the Near Northside. They met on their own to visit the site and refine the designs. The designers worked after regular hours to complete the design concepts, create renderings to communicate their ideas to a lay audience, and compile presentations with site analysis and design elements. The OAH team met internally near the end of those three weeks so that the two teams could present to each other and strengthen each other’s designs. A representative from CenterPoint attended that meeting to clarify the process of moving the utility pole and wires out of the future pocket park. Finally, the designers met with Toro to make sure her sculpture was coordinated with their designs.

The Competing Designs

OAH then facilitated a second community meeting where the teams presented their designs.

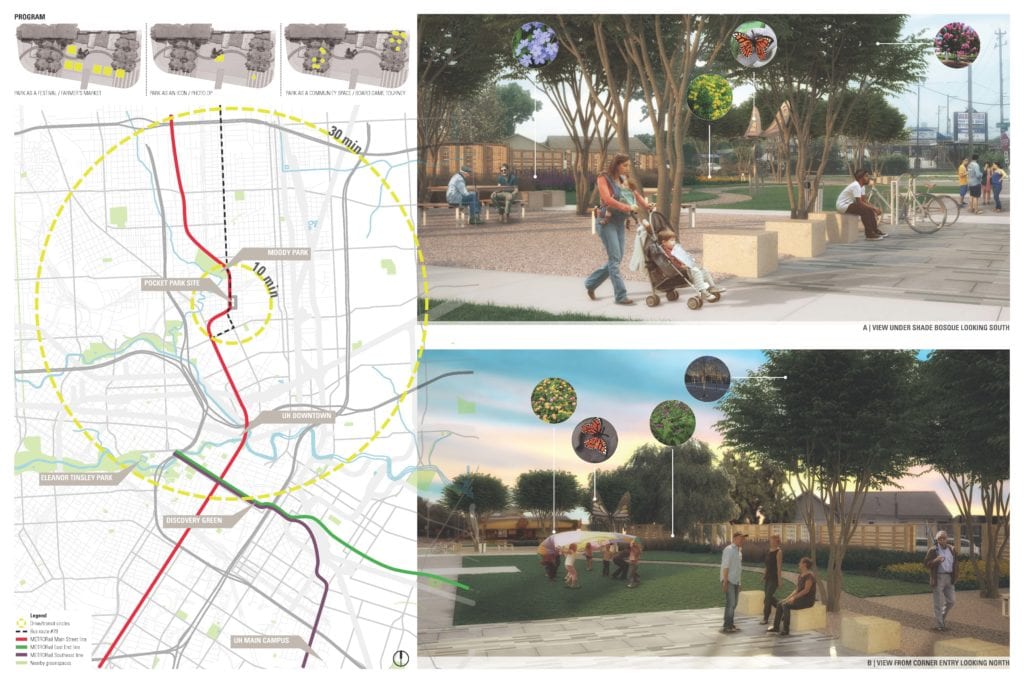

Team 1 created a design based on elements associated with a caterpillar’s life cycle. Where they saw pedestrians cutting through the lot they designed diagonal paths. They created buffer plantings along the back of the lot to soften the back fence and screen the view of the neighbors. Toro’s butterfly sculpture is at the intersection of the paths, and a plaza on the corner provides seating and a colorful painted pattern mimicking a Monarch caterpillar. Additional design elements they suggested included using colorful yarns to knit around the trunks of the trees and hanging hammocks for relaxing.

Team 2 used the geometry of the rail tracks and crosswalk to inform its rectilinear patterns in the design. Two copses on the north and south end of the park provide shade in plazas with chess boards and cubes for seats. Toro’s butterfly sculpture is in the center of the lawn, adjacent to a meandering path that winds from the north to the south side of the park. Planting beds and a fence screen the view of the neighbors to the east. The beds also maintain the rectilinear design concept and alternate between butterfly gardens and edible gardens.

Both teams presented their design concepts to the community members at the meeting. Here, community members were invited to ask questions. Questionnaires solicited further feedback on the designs and the community members’ like or dislike of specific features.

Developing a Final Design

The designers then had 10 days to integrate the feedback, create a phasing plan, and outline a budget for the project. Because of the short timeline, which was tied to Avenue CDC’s grant deadline for the project, it was impossible to combine elements from the two designs; instead, one design was chosen and refined. The final design is a variation on the original design by Team 2. The meandering path has been removed and a sculptural element has been added. Sculptural piping in bright colors will be used near the street in the southwest plaza as bike racks; larger versions will wind through the garden beds and ultimately be used to help support the butterfly sculpture.

Part of the community feedback from the initial design presentation was to find a way to honor Josue Flores in the park. Community members would like to name the park after him or create a memorial of some kind. The designers think that the north side of the park, which is separated from the butterfly sculpture and main lawn, would be a quiet space ideal for a memorial. The discussion about how exactly the community wants to honor Flores was discussed at the final design presentation.

Team 2 presented the final design to a well-attended super neighborhood meeting. After the presentation, designers and an OAH board member fielded questions from community members to explain design decisions and the process of community involvement throughout the design phase.

The designers from Team 2 presented their revised design at a beginning of a very well attended Super Neighborhood Meeting at the Leonel Castillo Community Center. Residents raised concerns about the park inviting the homeless to loiter and expressed their desire to not have a water feature. All of these concerns had been raised at previous steps in the design process, and we were able to explain this to the residents at the final design meeting. This meeting represented an opportunity to share the design process with a much larger audience than had previously participated in community meetings.

Open Architecture Houston helps facilitate projects up to the design development phase, so our involvement in this project is coming to a close. Next steps for the pocket park will be led by GNMD and include aligning with the Houston Parks Department’s design requirements, launching a fundraising campaign, and contracting a design firm to take the project through construction documents and construction management.

About the Author

Katherine Sargent Cairoli’s deep love of nature comes from a childhood of wandering through the woods and fields of her family’s farm in Southeastern Pennsylvania. After studying writing and science in college at Yale University and working on environmental justice in public health, Kate earned a Master’s degree in ecological design at the Conway School, and found a career in public interest design where she can combine all of her passions. She currently resides in Houston, TX and serves as the Director of Communications for Open Architecture Houston.

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.