by Thomas Berger, text and photos

Feeding the birds in winter has become a common practice so that we can support and enjoy them, and providing birds with nesting boxes is another way to help them survive in our man-made landscapes.

It is no different with insects. Besides growing their favorite food plants in our gardens, we now can provide shelter for overwintering and preserve or create nesting sites for our native bees and other important insects, like predatory wasps.

Nesting Habits of Bees and Wasps

Most bees and wasps have specific nesting habits, preferring nesting tunnels either in wood, hollow plant stems, or the ground.

Most bees gather pollen and nectar to provide food for their larvae. The food is deposited in a cell, separated by mud walls or, as in the case of leafcutter bees, wrapped in leaves. The eggs are placed on the pollen dough before the cells are sealed.

Table 1. Nesting locations of common bee and wasp genera |

||

| Ground-Nesters: | ||

| Bare patches of well-drained soil, most often sandy or silty loam that does not collapse when dry and is soft enough for digging, but some species nest in pure sand, others in river banks that are periodically inundated | Mining Bees | Andrena |

| Minute Mining Bees | Perdita | |

| Cellophane Bees | Colletes inaequalis | |

| Slender Sweat Bees | Lasioglossum | |

| Dark Sweat Bees | Halictus | |

| Green sweat Bees | Agapostemon, Augochlora, Augochlorella | |

| Digger Wasps | Sphex | |

| Horse Guard | Stictia | |

| Spider Wasps | Entypus | |

| Sand Wasps | Bembix | |

| Wood and Stem-Nesters: | ||

| Tunnels in trees, logs, rotting wood, and also hollow stems of herbaceous plants and grasses, as well as wooden structures and old masonry | Mason Bees | Osmia |

| Yellow-faced Bees | Hylaeus | |

| Carder Bees | Anthidium | |

| Leafcutter Bees | Megachile | |

| Large Carpenter Bees | Xylocopa | |

| Small Carpenter Bees | Ceratina | |

| Resin Bees | Anthidiellum, Dianthidium | |

| Mason Wasps | Euodynerus | |

| Cavity-Nesters: | ||

| Abandoned mouse nests, cavities in the soil, in trees and buildings, | Bumble Bees | Bombus |

| Paper Wasps | Polistes | |

| Yellow Jackets | Vespula | |

A mining bee carries pollen into her nest that she created in the sandy fill between walkway pavers.

Many different materials are used to create the separations between different nest cells and to close the nest entrances, or to line the inside of the nest. These materials include mud, chewed plant materials, plant hairs (Carder Bees), cut-out foliage or flower petals (Leafcutter Bees), a cellophane-like substance created by the bees themselves (Cellophane Bees), and resin collected from plants (Resin Bees).

Supporting the Ground Nesters

How can we support ground-nesting bees and other ground-nesting insects?

- Protect existing nesting sites (insects can be observed entering ground tunnels, small piles of soil often surround the entrances)

- Do not disturb the soil (avoid tilling, digging, vehicular traffic)

- Do not cover soil with mulch

- Maintain existing vegetation, which is usually sparse, by removing strong-growing plants (shrubs, invasive weeds)

- Nesting sites can be protected from predators like skunks and raccoons by covering the area with chicken wire

- Create man-made nesting sites for ground-nesting bees

- In gardens, areas can be dedicated for nesting sites. Rock gardens are ideal as they usually have well-draining soil and low vegetation. Some areas need to be kept free of vegetation. Rocks and clumps of perennials are helpful as orientation for bees to find their nest entrances. Bees choose sunny locations for their nesting sites and prefer slopes exposed to the southeast, which warm up quickly in the morning.

- Sandy loam can be purchased and a pile created on a sunny location. The pile can be covered with chicken wire and thinly planted with clumps of small grasses to stabilize the soil. Bees, wasps and burrowing beetles will be attracted to these piles. The volume needs to be in the range of several cubic yards of soil to allow for sufficient depth to accommodate insect burrows.

Supporting Tunnel-nesting Bees

How can we support bees nesting in wood tunnels and hollow stems?

- Leave dead trees standing as long as they are not a safety hazard.

- Do not remove dead wood and fallen trees from forests

- Pile up logs from cut trees (especially those containing burrows) to allow larvae of beetles, wood wasps and horntails to complete their life cycles, and to provide abandoned tunnels for nesting bees.

- Do not remove plant stems of dormant perennials and grasses from garden beds until early spring, and leave removed stems in a loose piles for as long as possible to allow young bees to hatch from their nesting material.

- Do not mow wild meadows more than once a year, ideally in early spring.

- In gardens and orchards set up bee hotels and bundles of nesting tubes, reeds and other hollow plant stems (dry stems of Japanese Knotweed are also very suitable)

- Provide access to nesting materials, especially mud or clay that is kept moist. A sophisticated mason bee mud box can be purchased via the internet (for example at crownbees.com). A simple dish containing clumps of clay and some water is also a welcome source of mud for mason bees and wasps.

- Provide fresh clean water in a dish or bird bath (cleaned and renewed daily is best)

- Allow for wet puddles on dirt roads and animal pastures as they are important sources of minerals to some butterflies and other insects.

A mud dish needs to be “watered” daily during the summer. When bees are collecting mud they are vulnerable to predation by birds. A wide-mesh chicken wire installed around the water source protects the insects.

Creating Bee Hotels

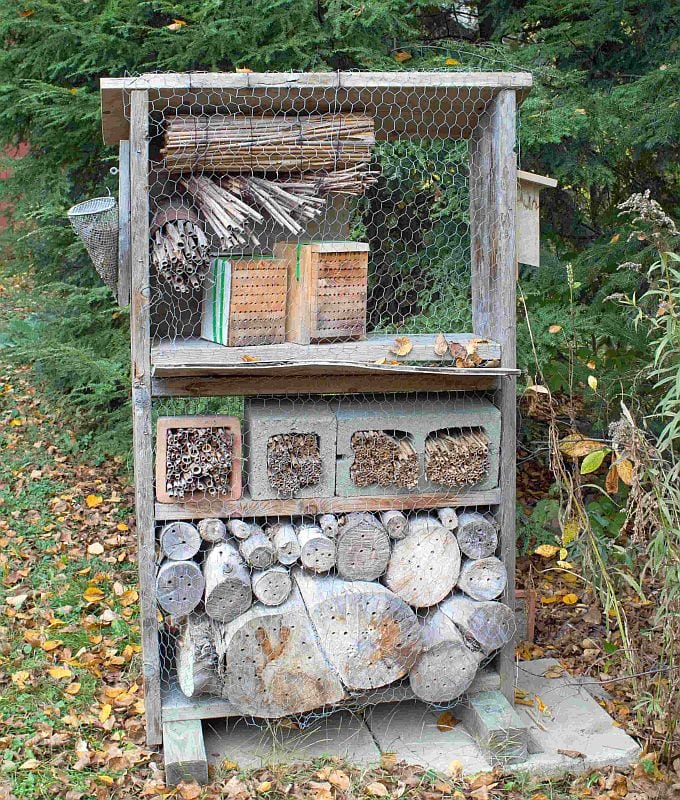

A bee hotel incorporates a variety of nesting materials. The front has been covered with coarse chicken wire to keep birds from pulling out the nesting reeds.

A bee hotel can be any kind of shelter that contains nesting sites for bees. Typically, bee hotels contain wood blocks with drill holes in various sizes, bundles of hollow plant stems or paper tubes, and blocks that are composed of fluted boards, which can be taken apart for cleaning.

Tunnels in drilled blocks or fluted boards should include the sizes shown in Table 2 in order to accommodate various bee species.

Table 2. Tunnel sizes to include in a bee hotel |

|||

| tunnel diameter | length (depth) | ||

| 2.5 to 6 mm | 3/32 to 1/4 inch | 8 to 13 cm | 3 to 5 inches |

| 7 to 10 mm | 3/8 to 1/2 inch | 13 to 15 cm | 5 to 6 inches |

In most bee species, the eggs laid deeper in the nest will be females; the eggs closer to the tunnel opening will be males. If the nesting tunnels are too short there will be fewer males. Since males hatch first they can be seen waiting for females in the area of nesting sites.

Nesting blocks can be created from fluted boards by using a rounded router bit to cut flutes into a board from both sides, and at equal locations. Leave approx. ¼” to 3/8 inch of space between flutes. Cut the board into sections of 6″ of length and pile them over each other to create the nesting block. The back end needs to be covered with an end board or well attached card board. The front can be flamed in irregular patterns to make it easier for the bees to find their nesting tunnels.

When using reeds and other hollow plant stems, the sizes identified in the table above are valid, and the depth is usually defined by a node in the stem. Simply cut the reeds to a length of at least 6 inches and discard any where the nodes are too close to the entrance.

Pithy canes, for example from raspberry and blackberry plants, are attractive to Small Carpenter Bees (Ceratina) and possibly other small bees.

Nesting tubes from cardboard can be homemade or purchased via the internet (www.crownbees.com).

Stems or tubes can be bundled and stacked into a box or can to protect them from the weather and predators. Make sure containers are installed in a way that water can drain out.

Bee hotels should be placed in a sunny location, with the entrance facing south-east, so that they can warm up quickly in the morning sun. In hotter climates, they should be somewhat shaded from the hot sun in the early afternoon. Bee hotels placed in shade will attract mason wasps instead of bees.

Opening a nesting block created from fluted boards reveals the brood cells of a Mason Wasp. Several caterpillars fill one cell, and clay mud is used to divide the cells from each other.

Maintaining Nesting Sites

Pests can build up in bee nesting locations, especially if many bees are present. These pests include bacterial and fungal diseases, mites, and parasitic wasps. In nature, old logs decay after a few years, so that new generations of bees need to find new locations, which are fresh and free of parasites.

Wood blocks in bee hotels are usually lifted off the ground and sheltered from rain, so that they last for many years. However, this allows for build-up of diseases and pest populations. It is necessary to remove wood blocks after two or three years. Since bee larvae or pupae can be inside the nesting blocks at any time of the year, it is necessary to allow the young bees to hatch. At the same time, you want to keep bees from building new nests in these old wood blocks. A good method is to place the wood blocks in a cardboard box with a small exit hole (½ inch diameter). The freshly hatched bees will follow the light to exit the box, but new bees will not find the block for nesting. This is best done in early spring, before the first new nests are built. Old blocks can also be placed in dark locations under trees where new bees will not likely search for nesting sites.

Reeds and other plant stems as well as cardboard rolls should also be renewed and can be handled in the same way.

Harvesting Cocoons

Cocoons of bees can be harvested and overwintered inside a humidifying box in a refrigerator to protect them from predators and diseases, but harvesting is only possible if the nests can easily be opened. This is the case with fluted board blocks and reed bundles. Bamboo faces the same problems as solid wood blocks, neither of which can be easily opened.

Harvesting from cardboard tubes can be facilitated with paper inserts, which are pulled out of the tubes and torn apart to release the bee cocoons.

The bee cocoons are stored until early spring and placed outdoors in an open box (but protected from birds and predators) on a warm day so bees can finish their development and hatch.

Bumblebee Boxes

In the wild, queen bumblebees start looking for nesting sites in early spring, with the latest species finishing by mid or late June (depending on region and climate). Preferred nesting sites are often abandoned mouse holes; bumblebees are attracted to the smell of old mouse nests. Other nesting sites can be dense clumps of dried grass and wall cavities. Finding suitable nesting sites that are protected from weather and predators is a major challenge for bumblebee queens.

Wooden or cardboard boxes can be provided as nesting sites for bumble bees, but generally the acceptance is less than 30%. Boxes should be 6 to 12 Inches long and wide, and approximately 4 Inches high on the inside. They can be placed in covered shelves to protect them from rain, or singly into the landscape, similar to bee hives, with a rain-proof cover. Bumblebee boxes need to have a tunnel-like entrance, and aeration has to be insured through openings on the lower and upper edge of the side walls.

Coarse material like fine twigs, a layer of reed or a flat clump of wire mesh can be placed in the bottom for drainage and insulation. Upon this a nest from wool or cloth is created, or an old mouse nests can be placed inside the box.

Other models are placed underground and have entrance pipes to the soil surface. Cavities in hay or straw bales have also been accepted as nesting sites and are among the easiest and most promising ways to provide housing for bumblebees.

Shelter for Overwintering

It’s important to provide shelter for overwintering insects:

- As much as possible, keep leaf litter in woodlands and garden beds where it falls.

- Create stone, brush and wood piles as shelters for overwintering insects.

- Wait to cut down old stems and clumps of perennials until late winter or early spring.

Sources

Mader, E., et al. 2011. Attracting Native Pollinators. The Xerces Society

Park, M., et al. 2012. Wild Pollinators of Eastern Apple Orchards and How to Conserve Them. Cornell University, Penn State University, and The Xerces society. URL: http://www.northeastipm.org/park2012

Von Hagen, E. 1986. Hummeln – bestimmen, ansiedeln, vermehren, schützen. Verlag Neumann-Neudamm

CrownBees: Native Bee Guide. www.crownbees.com

About the Author

Thomas Berger grew up in a small rural town in Germany. During his childhood he was an avid collector of shells, bones, sea creatures, and fossils. He also gardened with his father and kept bees and sheep which led him to study agriculture. As an adult, Thomas worked on farms in Germany, France and Australia, and joined the German Volunteer Service in 1984, working in an agricultural project in Niger, West Africa. In 1994 he moved to the United States, where he started a landscape design and construction firm, Green Art, and received an award of excellence from the New Hampshire Landscape Association in 1998. Thomas is a regionally known stone sculptor, expressing his love of nature through his art. Thomas has won many awards and commissions, and his sculpture is displayed at public venues throughout the Northeast.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.