By Joelle O’Daniel-Lopez

Symphyotrichum carolinianum with a species of hoverfly, oblique streaktail. I appreciate hoverflies because they are lovely to look at, but many species eat aphids when larvae and pollinators when adults.

When we purchased our home ten years ago, it had the typical suburban NW Florida yard with a mix of the good, the bad, and the ugly. We were fortunate to have several well-established “good” trees, including live and laurel oaks (Quercus virginiana & Quercus laurifolia), southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), and black cherry trees (Prunus serotina). The deciduous live oaks (Quercus virginiana), which appear to be evergreen, anchor the yard by spreading a wide dome-like canopy of strong, dense branches with dark green waxy leaves. Our trees shelter an astonishing variety of wildlife. This past spring, a kaleidoscopic mix of migrating birds busily refueled on the insects and caterpillars in the branches.

- Migrating prothonotary warbler hunting in oak tree.

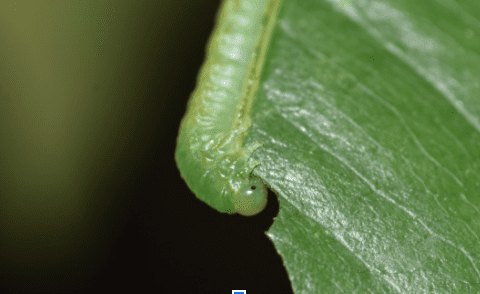

- Macro photograph of larvae eating black cherry tree leaf.

We encourage healthy growth and reduce hurricane damage to our wonderful native trees by periodically hiring a certified arborist to remove weaker limbs and trim them. Our arborist uses the light touch of an artist, which mitigates the damage of storms like Hurricane Sally, where damage and clean-up could have been much worse. Speaking of Hurricane Sally, gardening around the house had been held hostage, waiting for our roof to be replaced. We were approved for a replacement roof in the early summer, but due to insurance hassles and other maddening delays, it didn’t come to fruition till October!

Before photo, the whole backside of the house was lined with nandina.

Also, in support of the “good” plants and trees, we quickly got rid of the “bad” and “ugly” nonnative invasive species like Chinese tallow (Triadica sebifera) and Mexican petunia (Ruellia simplex). Getting rid of the nandina (Nandina domestica) has been a slower process to replace with native plants. Nandina is listed as an invasive species for Florida, is closely related to bamboo, and was initially brought from Asia as an ornamental flowering shrub with clusters of red berries appearing in the fall/winter. Those berries are toxic to wildlife (especially birds), so they definitely have to go. This summer, our greatest achievement was removing a strip of nandina that was 25 feet long by two feet wide from around the house. This accomplishment brought us to about 85% completion of nandina removal from the property. We do not use herbicides and have mechanically removed the nandina. Removal has to be a complete removal from the root as any remaining bits will come back. For sections with just nandina, this battle armed with shovels and pickaxe is “easier” than when the roots are entangled with the far-reaching roots of nearby magnolias. Thankfully the enemy distinguishes itself by having saffron yellow roots (inside).

We removed nandina from this area (pictured left) last year and replaced it with natives. Upfront is Louisiana irises, false nettle (Boehmeria cylindrica), garden phlox (Phlox paniculata). Narrowleaf sunflower (Helianthus angustifolius) is beginning to come up around the stake that will be needed later in the season to support it, especially during storms. Further in the background spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis), Florida anise (Illicium floridamum), beyond that is blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium angustifolium), lyreleaf sage(Salvia lyrata).

In the garden section where we most recently removed nandina, I planted:

- Dwarf viburnums (Viburnum obovatum (Mrs. Schiller’s Delight),

- Ashe calamint (Calamintha ashei),

- False rosemary (Conradina canescens)

- Twin flower (Dychloriste oblongifolia)

- Stoke’s aster (Stokesia laevis)

- Narrowleaf silkgrass (Pityopsis graminifolia)

- Scarlet Calamint (Clinopodium coccineum)

- I drew native plant-inspired scenes on my windows with window crayons to prevent migrating bird strikes and as nice afternoon entertainment with my daughter.

- Shady side garden made a great COVID lockdown project.

This narrow side yard garden was an underutilized eyesore until we tackled it this year as a Covid lockdown project. We planted more shade-tolerant species, including wooly dutchman’s pipevine (Aristolochia tomentosa) to attract pipevine swallowtails, harryjoint meadow parsnip (Thaspium barbinode) to attract eastern black swallowtails. We also added columbine (Aquilegia canandensis). For this year’s experiment, I acquired my late father’s fountain from my mom’s house. I added a solar bubbler and rocks as I wanted the sound of water to attract birds. I transplanted some moss and resurrection fern (Pleopeltis polypodioides) at the top to see if it would attach to the concrete. I also added a pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata), and so far, it has survived! During the recent roof replacement, I’m thankful the contractor leaned full sheets of plywood over this area as some of these plants are nearly irreplaceable.

Hypericum hypericoides and Vernonia gigantea.

Also, in this side yard, I planted St. Andrews cross (Hypericum hypericoides) and giant ironweed (Vernonia gigantea.) I discovered Hypericum hypericoides growing in my “freedom lawn,” and I have slowly been transplanting it around the house as it forms a nice mounding flowering form. Vernonia gigantea was purchased originally from a native nursery, and since then, it has been spreading by seed. Vernonia gigantea is such a powerhouse for pollinators as I have seen many different native bees, wasps, moths, and butterflies benefitting from it.

Gulf Fritillary on Vernonia gigantea.

In gardening with native plants, my primary driver is for pollinators and birds. Many birds, including hummingbirds, need insects. To bring the insects, you need native plants, especially trees, that can support hundreds of species of insects. This spring, our family got to watch eastern bluebird parents hunt the yard for bugs for their fledglings. Exploring and photographing the wildlife in my yard has been like therapy dealing with this past year with the lockdowns, including the periodic closure of my beloved Gulf Islands National Seashore. Nothing is more exciting than seeing a new bird or butterfly visit my yard. It makes me smile when spotting missing chunks out of leaves from leafcutter bees or caterpillars. To date, I have observed 34 different species of butterflies in my suburban yard.

- Long-tailed skipper on Helianthus angustifolius

- Ruby-throated hummingbird on Lonicera sempervirens

In my area, the nearest native plant nursery is three counties over, and the owners retired this fall, creating a major void for finding native plants in NW Florida. I bought several native plants before they closed their gate but couldn’t buy as many as I wanted due to our pending repair work to the roof. In the last year, due to COVID, some of the regular local garden events with native plants did not occur, such as the annual sale at the greenhouse of the university. Recently I have been able to get some natives locally through sharing and exchanging with fellow native plant enthusiasts and small outdoor markets. There is hope locally for native plants without driving three hours away to Tallahassee. Another growing rumor is a pre-order market is opening soon. Additionally, a burgeoning resource growing a variety of natives is a campground and garden with a native plant-minded horticulturist at the helm. I hope this resource continues to expand.

Sandhill milkweed (Asclepias humistrata) grows naturally at nearby Gulf Islands National Park.

A couple of local nurseries in the area carry a few natives, especially native milkweeds due to increasing local demand to support the monarch. However, the main natives sold- Asclepias incarnata and Asclepias perennis – prefer “wetter” conditions than most “yards” provide without irrigation. Plus both species are not very large plants and cannot support many caterpillars. A. syriaca, with its tall stems and large leaves, does not naturally occur in Florida.

In my personal search for growing native milkweeds, I ultimately wanted to grow Asclepias humistrata. As I child, I remember seeing monarch caterpillars on this milkweed grow in the sugar-white sand dunes of Pensacola Beach, FL. This particular milkweed, like many native milkweeds, is unavailable at nurseries due to its extensive taproot best suited for growing in poor sandy soils. This year I was fortunate to receive several A. humistrata seeds. More serendipitously, a recent graduate student, Gabriel Campbell, completed his Ph.D. on researching growing A. humistrata, especially for restoration projects. The Florida Native Plant Society produced an informative Lunch and Learn video on “Propagation & Restoration of Sandhill Milkweed (Asclepias humistrata) with Gabriel Campbell, Ph.D.” on Youtube. This video is based on Gabriel Campbell’s exit seminar for his Ph.D. and guided me through growing A.humistrata from seed. I am most excited to plant sandhill milkweed and watch them grow for years to come.

Macro photograph of Phyla nodiflora bloom with ants.

Mimosa strigillosa and Phyla nodiflora

Another yard project I have been working on is placing sunshine mimosa (Mimosa strigillosa) and turkey tangle frogfruit( Phyla nodiflora) as ground cover. Both plants are butterfly hosts and produce lovely flowers throughout the year, attracting pollinators, and happily, both have demonstrated themselves to be hardy and resilient plants.

- American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) from spring to late fall.

- Gray catbird enjoying American beauty berries.

In planting for wildlife, I grow a wide variety of plants, considering both nectar sources and host plants, and plan for different seasons. Seasons’ passage in Florida is subtle. In the spring, I look forward to the Chickasaw plums blooming (Prunus angustifolia), the early bees visiting spiderwort blooms (Tradescantia ohiensis), the black cherry tree (Prunus serotina) bursting with new leaves and caterpillars! The returning migrating birds somehow seem to know when the US is full of nutritious larvae again across the Gulf. Most anticipated in late spring is waiting for the Ashe magnolia (Magnolia macrophylla var. ashei) and southern magnolias (Magnolia grandiflora) to bloom. Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) and stoke’s aster (Stokesia laevis) marks early summer. At the same time, I patiently watch the giant ironweed (Vernonia gigantea) grow taller and taller till it finally erupts in purple blooms and brings a plethora of pollinators. Fall is full of sprays of yellows and purples with goldenrods (Solidago), blazing star (Liatris), muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris), and golden asters (Chrysopsis). Late fall is when I look forward to seeing the climbing aster bloom (Amplelaster carolinianus) and forked bluecurls (Trichostema dichotomum) bloom.

In planting for wildlife, I grow a wide variety of plants, considering both nectar sources and host plants, and plan for different seasons. Seasons’ passage in Florida is subtle. In the spring, I look forward to the Chickasaw plums blooming (Prunus angustifolia), the early bees visiting spiderwort blooms (Tradescantia ohiensis), the black cherry tree (Prunus serotina) bursting with new leaves and caterpillars! The returning migrating birds somehow seem to know when the US is full of nutritious larvae again across the Gulf. Most anticipated in late spring is waiting for the Ashe magnolia (Magnolia macrophylla var. ashei) and southern magnolias (Magnolia grandiflora) to bloom. Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) and stoke’s aster (Stokesia laevis) marks early summer. At the same time, I patiently watch the giant ironweed (Vernonia gigantea) grow taller and taller till it finally erupts in purple blooms and brings a plethora of pollinators. Fall is full of sprays of yellows and purples with goldenrods (Solidago), blazing star (Liatris), muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris), and golden asters (Chrysopsis). Late fall is when I look forward to seeing the climbing aster bloom (Amplelaster carolinianus) and forked bluecurls (Trichostema dichotomum) bloom.

I was surprised to see this native green anole hunt for little bees by intercepting them visiting Coreopsis lanceolata.

Another frequent flowerer is Coreopsis lanceolata, which blooms from spring to fall but mainly peaks late spring and early summer. I have a sunny area that they readily reseed and fill. I could easily fill an article’s worth of photos of the pollinators and activity around the Coreopsis lanceolata alone.

Green-fly orchid (Epidendrum magnoliae)

The small epiphyte orchid can typically be found on old trees like live oaks or magnolias. A friend gave me some after a storm knocked rotten soft branches down, with the orchids and resurrection fern (Pleopeltis polypodioides) still attached.

As the growing season closes, I will miss seeing all the activity in the yard, especially the butterflies. I am collecting and organizing the last of the seeds for the year. I am already daydreaming of my next native gardening adventures and plotting the next plant beds.

Megachile xylocopoides on Helianthus floridanus

About the Author

Joelle O’Daniel-Lopez, an environmental protection professional, is happiest photographing the natural world. She finds sharing her view celebrating the tiny and fleeting moments of wonder helps her and others to a larger appreciation of nature and its complexity. She is working towards transforming her yard to native plants in support of wildlife, especially birds and butterflies.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.