The following excerpt is from Home Outside: Creating the Landscape You Love by Julie Moir Messervy (The Taunton Press, 2009), pages 171-173.

Auditing Energy

It may sound strange, but the first thing I do when I visit a new property is to perform a kind of mental “energy audit” on the landscape. I’m not talking about reviewing the efficient use of electrical energy on a site. What I check for are the “forces”—their direction and magnitude—that radiate from each particular site and the house, vegetation, and landscape elements that sit upon it.

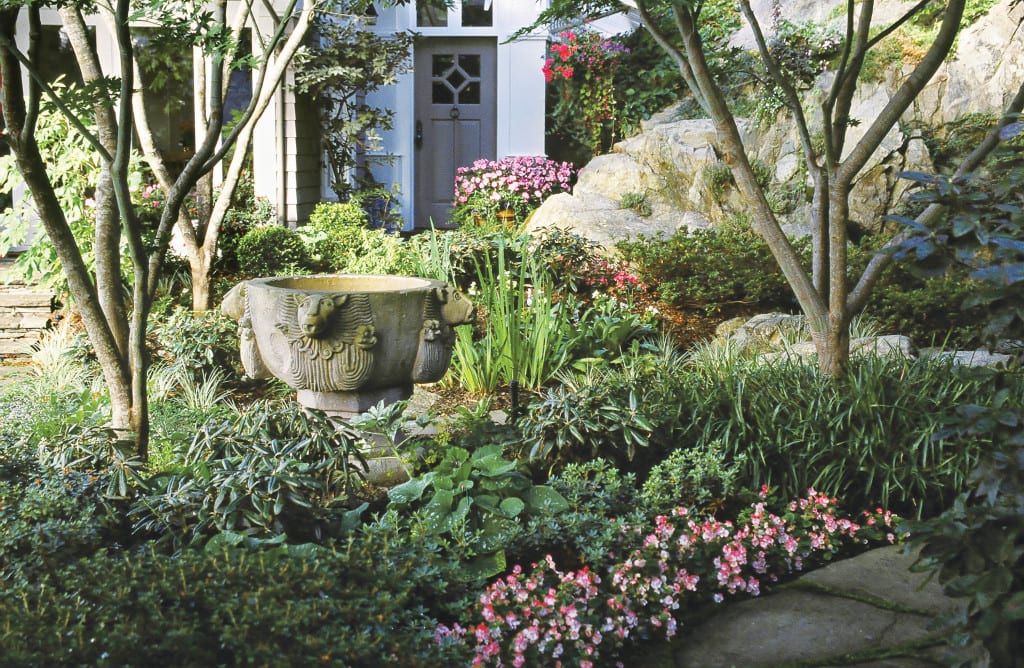

Twin trees frame a handsome urn that sits nestled within a verdant planting. Block out one of the trees with your hand, and you’ll instantly see that the energy feels less balanced. Photo courtesy Ron Rule Consultants.

The two homes I grew up in each possessed a different kind of energy. Our first house was a new colonial in a subdivision in Illinois, built on former pastureland. The only feature on the property besides the house was a large maple tree; everything else on our half acre of grass was flat, open, and bland. As you looked out from the house, there was initially nothing to draw your attention or to stop your eye except the edge of the forest beyond the property line. Over the 11 years we lived there, my parents added landscape elements: stone walls, an arbor, a brick patio, a large vegetable garden, a swing set, and a new garage, creating frames and focal points that caught the eye and focused the energies there.

You can see abstract patterns of energy in nature as well as in your own backyard. In this landscape, your eye starts at the large stone, follows the curving path of grasses, and moves through the view framed by two small trees. Photo by ©Genevieve Russell.

Our next home, sited on a wooded hillside in Connecticut, was a stately house with formal flower gardens built on terraces. Here, the problem was the exact opposite of our first home: Every space in the large backyard was filled up with flower beds, narrow paths, and overgrown trees so that it all felt chaotic and uncontrolled and too much for a busy family to care for. What we ended up doing was give the property more “breathing room” by turning some of those high-maintenance landscapes back into grass. In both cases, by adding or subtracting elements we found ways to manage the energy to create visually satisfying homes outside.

Seeing in the Abstract

One way to observe the flow of “energy” in and around your property is to see it in the abstract, as an Impressionist painter might. Scrunch up your eyes or remove your glasses or contact lenses so that the different elements lose clarity and focus and look fuzzy. Tall trees become large blobs of green and vertical lines; a flower bed becomes a thick line of color; lawn becomes field; walls turn into dark lines running across the landscape. The view you take in becomes an abstract painting of soft textures, dabs of color, looming volumes, and curving or straight lines that may be altered to suit your aesthetic needs. When you see the landscape as a blur, you focus less on the details and more on the overall forms in front of you. You’ll find that you can mentally rearrange blocks of elements with ease, imagining adding a splash here and removing a blob there.

There are two ways to “see” your landscape: in focus, when you observe the details of objects such as the cherry tree in the foreground, or out of focus, when you’re aware of the general shape and abstract patterns of groupings of elements like the blurry ball in the background. When you blur the details and see the landscape in the abstract, it’s easier to see how to place the pieces. Photo by ©Genevieve Russell.

About the Author

Julie Moir Messervy is a distinguished author and award-winning landscape designer. Julie’s vision for composing landscapes of beauty and meaning is furthering the evolution of landscape design and changing the way people create and enjoy their outdoor surroundings. Julie is the principal designer of JMMDS, a landscape architecture and design firm in Saxtons River, Vermont, creators of parks and residential gardens around the country. Her best-known work, the three-acre Toronto Music Garden, was designed in collaboration with noted cellist Yo-Yo Ma and received the Leonardo da Vinci Award for innovation and creativity. She is the author of eight books on landscape design, including Landscaping Ideas That Work; Home Outside: Creating the Landscape You Love; and Outside the Not So Big House with Sarah Susanka. She has written numerous articles, including the long-running “Inspired Design” column for Fine Gardening magazine. Julie has a mission to use digital technologies to bring great design to anyone, anywhere and has created landscape design apps for that purpose.