by Josh Fodor

Farms worldwide have contributed greatly to the loss of native vegetation and wildlife habitat. Over the past twenty years native plants have begun to creep back in around the edges of farms as the utility of ‘farmscaping’ has been demonstrated. There are many practical and policy level challenges to successfully integrating native plants onto farms and maintaining their associated habitat values.

Farmscaping is a whole-farm, ecological approach to pest management. It is defined as the use of hedgerows, insectary plants, cover crops, and water reservoirs to attract and support populations of beneficial organisms such as insects, bats, and birds of prey.

Farmscaping with native plants supports the habitat needs of beneficial organisms by providing shelter, nesting and over-wintering sites, and sources of nectar and pollen. Native insect pollinators and native birds are two groups that benefit greatly from farmscaping, and in turn they provide great benefit to the farm production.

According to the Xerces Society Fact Sheet ‘Farming with Pollinators,’ the pollination activity of native insect pollinators compares favorably to honey bees. In fact native pollinators are on the job earlier, work longer hours, are more active in colder and wetter weather, and are more efficient in distributing pollen when compared with honey bees.

Native birds are effective at controlling insect pests including caterpillars, ants, grubs, leafhoppers, aphids, snails, scale insects, and codling moth. One study found that insectivorous birds, including downy woodpeckers and chestnut-backed chickadees, ate 85% of the over-wintering codling moths in California apple orchards (Baumgartner, 2001).

Native Plant Hedgerows

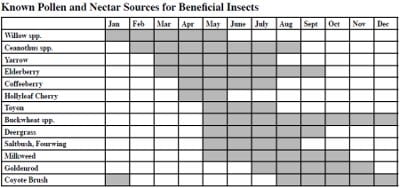

Planting a hedgerow is one farmscaping technique that is easy to install and provides many of the benefits outlined above. The chart below shows that planting a diversity of native perennials, shrubs, and trees ensures that there are pollen and nectar sources available throughout the year.

Table 1

Note: Grey boxes indicate the plant flowering period. Source: Kimball, M., and C. Lamb. 2001. See References below for complete notation.

As part of a three year study conducted by Community Alliance with Family Farmers (CAFF), Central Coast Wilds designed and installed farmscaping plans for six farms in the Pajaro Valley of California. The project was funded by State Water Resources Control Board. Collaborators on the project included Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems (CASFS) who conducted insect monitoring and the Coastal Watershed Council who conducted water quality monitoring.

A total of 17 farmscape practices were installed, eight of which were set up as monitoring locations – four for water quality and four for insect activity. The project goals were to:

- Reduce sediment transport by providing vegetated buffers between farmland and waterways

- Reduce nutrient load by providing hedgerows and buffer strips of grass, sedge, and rush, which perform nutrient uptake

- Reduce pesticide use by increasing biological pest control from beneficial insects in flowering hedgerows

- Improve habitat for beneficial insects, terrestrial animal, and plant species

After the farmscaping practices were installed, field days were conducted by CAFF to give farmers in the region an opportunity to learn about the techniques. A cost analysis was prepared in order to provide farmers with a tool to budget for implementing hedgerow systems on their farms.

Table 2

Hedgerow System Cost Analysis

Food Safety and the Future of Farmscaping

Food Safety and the Future of Farmscaping

There are many challenges to the creation of wildlife habitat on farms. Farmers rightfully have concerns that farmscaping will encourage pest species that eat or otherwise damage their cash crops. After decades of effort, and significant public investment, to integrate beneficial wildlife habitat back into working farms, a major setback has emerged over the perceived threat to food safety.

In 2006 the concern turned to alarm in California when several people died from spinach contaminated with E. coli 0157. Producers of fresh greens suffered large financial losses as consumers stopped buying bagged lettuce. Although no direct link between E. coli and native vegetation or wildlife has been documented, fear of such a link has resulted in the removal of all non-crop vegetation in and around leafy green production areas.

Growers of leafy green vegetable products were required by large produce buyers (e.g. grocery chains) to implement ‘clean farming’ practices: remove vegetation and create bare ground buffers between crops and habitat areas, and to trap, poison, and fence out wildlife if they wanted to sell their crops. Although the removal of non-crop vegetation has not been shown to reduce the risk of E. coli contamination, the vegetation loss has resulted in increased soil erosion, a decline in water quality and the elimination of important habitat for beneficial wildlife species.

The mandate to remove vegetation runs counter to research showing that non-crop vegetation can effectively filter water- and dust-borne pathogens. Specifically, University of California Santa Cruz researchers have documented that just a few meters of a grass buffer strip can filter E. coli.

Farmscaping offers an alternative to “clean farming” that requires removal of all non-crop plants from a growing area. Photo by Sam Earnshaw

Nearly six years after the food safety crisis emerged, the implementation of science-based farmscaping appears to be back on track. On January 4th, President Obama signed the Food Safety Modernization Act, with the Boxer amendment that strips the bill of wildlife-threatening enforcement against “animal encroachment” of farms. Instead, it will require FDA to apply sound science to any requirements that might impact wildlife and wildlife habitat on farms.

Specific to conservation-based agriculture, the main text of the bill states that rulemaking will “take into consideration … conservation and environmental practice standards and policies established by Federal natural resource conservation, wildlife conservation, and environmental agencies; and in the case of production that certified organic, not include any requirements that conflict with or duplicate the requirements of the national organic program.”

With the passage of this important legislation, Farmscaping can once again be used as a key conservation practice for enhancing biological diversity, ensuring clean water and increasing the viability of small farms.

References

Citations and sources of information about farmscaping for pest control and wildlife habitat are:

- Photographs courtesy of Sam Earnshaw, Community Alliance with Family Farmers

- Agricultural Cropping Patterns: Integrating Wild Margins – A Wild Farm Alliance Briefing Paper

- Baumgartner, JoAnn. 2001. Birds, Spiders Naturally Control Codling Moths. Tree Fruit Magazine, April 2001.

- Farmscaping to Enhance Biological Control ATTRA Pest Management Guide

- Farming with Food Safety and Conservation in Mind

- Food Safety versus Environmental Protection on the Central California Coast: Exploring the Science Behind an Apparent Conflict

- Hedgerows for California Agriculture: A Resource Guide

- Kimball, M., and C. Lamb. 2001. Establishing hedgerows for pest control and wildlife, pp. 11-15.* In P. Robbins, R. et al. [eds.], Bring farm edges back to life! How to enhance your agriculture and farm landscape with proven conservation practices for increasing the wildlife cover on your farm. Yolo Co. Resource Conservation District, Woodland, CA.

- The Xerces Society Invertebrate Conservation Fact Sheet: Farm with Pollinators – Increasing Profit and Reducing Risk

About the Author

Josh Fodor is the owner of Ecological Concerns Inc. (ECI) and Central Coast Wilds (CCW) nursery in Santa Cruz. ECI is a landscape firm specializing in ecological landscaping and habitat restoration, and CCW is a California native plant nursery. Josh can be found at www.centralcoastwilds.com or jtfodor@ecologicalconcerns.com.