By Leah Penniman

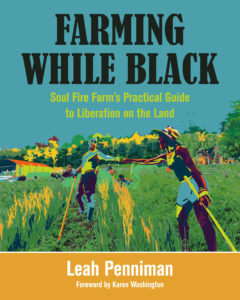

The following excerpt is adapted from the introduction of Leah Penniman’s book Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land (Chelsea Green Publishing, November 2018) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher and the author.

As a young person, and one of three mixed-race Black children raised in the rural North mostly by our white father, I found it very difficult to understand who I was. Some of the children in our conservative, almost all-white public school taunted, bullied, and assaulted us, and I was confused and terrified by their malice. But while school was often terrifying, I found solace in the forest. When human beings were too much to bear, the earth consistently held firm under my feet and the solid, sticky trunk of the majestic white pine offered me something stable to grasp. I imagined that I was alone in identifying with Earth as Sacred Mother, having no idea that my African ancestors were transmitting their cosmology to me, whispering across time, “Hold on daughter—we won’t let you fall.”

As a young person, and one of three mixed-race Black children raised in the rural North mostly by our white father, I found it very difficult to understand who I was. Some of the children in our conservative, almost all-white public school taunted, bullied, and assaulted us, and I was confused and terrified by their malice. But while school was often terrifying, I found solace in the forest. When human beings were too much to bear, the earth consistently held firm under my feet and the solid, sticky trunk of the majestic white pine offered me something stable to grasp. I imagined that I was alone in identifying with Earth as Sacred Mother, having no idea that my African ancestors were transmitting their cosmology to me, whispering across time, “Hold on daughter—we won’t let you fall.”

I never imagined that I would become a farmer. In my teenage years, as my race consciousness evolved, I got the message loud and clear that Black activists were concerned with gun violence, housing discrimination, and education reform, while white folks were concerned with organic farming and environmental conservation. I felt that I had to choose between “my people” and the Earth, that my dual loyalties were pulling me apart and negating my inherent right to belong. Fortunately, my ancestors had other plans. I passed by a flyer advertising a summer job at The Food Project, in Boston, Massachusetts, that promised applicants the opportunity to grow food and serve the urban community. I was blessed to be accepted into the program, and from the first day, when the scent of freshly harvested cilantro nestled into my finger creases and dirty sweat stung my eyes, I was hooked on farming. Something profound and magical happened to me as I learned to plant, tend, and harvest, and later to prepare and serve that produce in Boston’s toughest neighborhoods. I found an anchor in the elegant simplicity of working the earth and sharing her bounty. What I was doing was good, right, and unconfused. Shoulder-to-shoulder with my peers of all hues, feet planted firmly in the earth, stewarding life-giving crops for the Black community—I was home.

As it turned out, The Food Project was relatively unique in terms of integrating a land ethic and a social justice mission. From there I went on to learn and work at several other rural farms across the Northeast. While I cherished the agricultural expertise imparted by my mentors, I was also keenly aware that I was immersed in a white-dominated landscape. At organic agriculture conferences, all of the speakers were white, all of the technical books sold were authored by white people, and conversations about equity were considered irrelevant. I thought that organic farming was invented by white people and worried that my ancestors who fought and died to break away from the land would roll over in their graves to see me stooping. I struggled with the feeling that a life on land would be a betrayal of my people. I could not have been more wrong.

At the annual gathering of the Northeast Organic Farming Association, I decided to ask the handful of people of color at the event to gather for a conversation, known as a caucus. In that conversation I learned that my struggles as a Black farmer in a white-dominated agricultural community were not unique, and we decided to create another conference to bring together Black and Brown farmers and urban gardeners. In 2010 the National Black Farmers and Urban Gardeners Conference (BUGS), which continues to meet annually, was convened by Karen Washington. Over 500 aspiring and veteran Black farmers gathered for knowledge exchange and for affirmation of our belonging to the sustainable food movement.

Through BUGS and my growing network of Black farmers, I began to see how miseducated I had been regarding sustainable agriculture. I learned that “organic farming” was an African-indigenous system developed over millennia and first revived in the United States by a Black farmer, Dr. George Washington Carver, of Tuskegee University in the early 1900s. Dr. Booker T. Whatley, another Tuskegee professor, was one of the inventors of community-supported agriculture (CSA), and that community land trusts were first started in 1969 by Black farmers, with the New Communities movement leading the way in Georgia.

Learning this, I realized that during all those years of seeing images of only white people as the stewards of the land, only white people as organic farmers, only white people in conversations about sustainability, the only consistent story I’d seen or been told about Black people and the land was about slavery and sharecropping, about coercion and brutality and misery and sorrow. And yet here was an entire history, blooming into our present, in which Black people’s expertise and love of the land and one another was evident. When we as Black people are bombarded with messages that our only place of belonging on land is as slaves, performing dangerous and backbreaking menial labor, to learn of our true and noble history as farmers and ecological stewards is deeply healing.

Fortified by a more accurate picture of my people’s belonging on land, I knew I was ready to create a mission-driven farm centering on the needs of the Black community. At the time, I was living with my Jewish husband, Jonah, and our two young children, Neshima and Emet, in the South End of Albany, New York, a neighborhood classified as a “food desert” by the federal government. On a personal level this meant that despite our deep commitment to feeding our young children fresh food and despite our extensive farming skills, structural barriers to accessing good food stood in our way. The corner store specialized in Doritos and Coke. We would have needed a car or taxi to get to the nearest grocery store, which served up artificially inflated prices and wrinkled vegetables. There were no available lots where we could garden. Desperate, we signed up for a CSA share, and walked 2.2 miles to the pickup point with the newborn in the backpack and the toddler in the stroller. We paid more than we could afford for these vegetables and literally had to pile them on top of the resting toddler for the long walk back to our apartment.

When our South End neighbors learned that Jonah and I both had many years of experience working on farms, from Many Hands Organic Farm, in Barre, Massachusetts, to Live Power Farm, in Covelo, California, they began to ask whether we planned to start a farm to feed this community. At first, we hesitated. I was a full-time public school science teacher, Jonah had his natural building business, and we were parenting two young children. But we were firmly rooted in our love for our people and for the land, and this passion for justice won out. We cobbled together our modest savings, loans from friends and family, and 40 percent of my teaching salary every year in order to capitalize the project. The land that chose us was relatively affordable, just over $2,000 an acre, but the necessary investments in electricity, septic, water, and dwelling spaces tripled that cost. With the tireless support of hundreds of volunteers, and after four years of building infrastructure and soil, we opened Soul Fire Farm, a project committed to ending racism and injustice in the food system, providing life-giving food to people living in food deserts, and transferring skills and knowledge to the next generation of farmer-activists.

Our first order of business was feeding our community back in the South End of Albany. While the government labels this neighborhood a food desert, I prefer the term food apartheid, because it makes clear that we have a human-created system of segregation that relegates certain groups to food opulence and prevents others from accessing life-giving nourishment. About 24 million Americans live under food apartheid, in which it’s difficult to impossible to access affordable, healthy food. This trend is not race-neutral. White neighborhoods have an average of four times as many supermarkets as predominantly Black communities. This lack of access to nutritious food has dire consequences for our communities. Incidences of diabetes, obesity and heart disease are on the rise in all populations, but the greatest increases have occurred among people of color, especially African Americans and Native Americans.

Farming While Black is a reverently compiled manual for African-heritage people ready to reclaim our rightful place of dignified agency in the food system. To farm while Black is an act of defiance against white supremacy and a means to honor the agricultural ingenuity of our ancestors. As Toni Morrison is reported to have said, “If there’s a book you really want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Farming While Black is the book I needed someone to write for me when I was a teen who incorrectly believed that choosing a life on land would be a betrayal of my ancestors and of my Black community.

Leah Penniman is a Black Kreyol farmer and the 2019 recipient of the James Beard Foundation Leadership Award. She currently serves as founding co-executive director of Soul Fire Farm in Grafton, New York, a people-of-color led project that works to dismantle racism in the food system. She is the author of Farming While Black (Chelsea Green Publishing, November 2018). Find out more about Leah’s work at www.soulfirefarm.org and follow her @soulfirefarm on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Leah Penniman is a Black Kreyol farmer and the 2019 recipient of the James Beard Foundation Leadership Award. She currently serves as founding co-executive director of Soul Fire Farm in Grafton, New York, a people-of-color led project that works to dismantle racism in the food system. She is the author of Farming While Black (Chelsea Green Publishing, November 2018). Find out more about Leah’s work at www.soulfirefarm.org and follow her @soulfirefarm on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.