First Step to Maintain Biodiversity? Acknowledge Indigenous Knowledge as Science

Written by: ELA Director, Mads McELgunn, MA

Since reading Robin Wall Kimmerer’s 2013 book, Braiding Sweetgrass, I’ve been patiently waiting for mainstream publications to acknowledge a simple truth: Indigenous knowledge is science.

In the most recent IPCC report published in April, the international body acknowledged past and on-going patterns of inequity such as colonialism and governance as a cause of climate change, but did not go into great detail beyond this statement. It does not take someone deeply involved with the IPCC to recognize that centuries of expansion have had a significant toll on the environment. Interestingly, though, these scientists have yet to call on Indigenous communities for positive change based on eons of knowledge in conservation.

Currently, 80% of the planet’s biodiversity is on Indigenous lands. This means less than 5% of the human population protects most of our biodiversity. We often hear the refrain “America was natural, untouched beauty before we arrived,” but we now know this sentiment to be false. It took generations of careful, intentional land stewardship to cultivate the land we know as North America.

As we face an increasingly severe lack of biodiversity in our landscapes, now is the time for cross-cultural collaboration. However, the opportunity to do so is being threatened by the loss of Indigenous languages.

There are more than 7000 known Indigenous languages, with 40% at risk of becoming extinct. Nowhere is language more at risk than as it impacts plant knowledge. In North America alone, 86% of Indigenous plant knowledge comes from endangered languages. We must work to keep these languages alive through greater understanding of the ecology of the land in an effort to continue to support some of the world’s oldest and greatest knowledge of biodiversity. ELA is especially equipped in this regard as our mission demands we make change.

On average, around 3% of Indigenous plant knowledge and use is lost annually in adults. Linguist Ana Vilacy Galucia said, “Indigenous languages encompass entire knowledge systems about biodiversity, social organization, and the management of the environment.” Without access to these centuries long lessons, immeasurable loss in environments may occur.

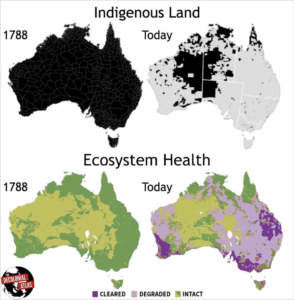

One of the most heavily studied populations of Indigenous communities, the Ticuna people of the Amazon, has had less than 5% of their plant knowledge documented. It is important to note, however, translating endangered languages does not translate the knowledge systems of these groups. It is only through direct and intentional interactions can Indigenous knowledge be shared. Uldarico Matapí Yucana, the Shaman of the Matapí in the Colombian Amazon Rainforest, said “When you destroy a territory, you destroy nature, knowledge, our practices, and our life.” This destruction has been documented across several continents. In the map below from the Decolonial Atlas, it is clear to see that the destruction of native lands has had a direct, negative impact on healthy ecosystems.

As ELA continues to grow and expand to other regions, it is important to keep in mind our responsibility as land stewards. The community of ELA is one that is diverse, curious, and collaborative. It is through these interactions and relationships that we can begin to repair the damage on the lands we tend.

The Ecological Landscape Alliance educates, inspires, and empowers people to value biodiverse landscapes and employ ecological practices. It is this mission statement that powers all of ELA’s activity, and it is this mission that speaks to the need to diversify our education and hold a place for Indigenous communities to be a part of this organization and community.