by Jessamine (Jessa) Finch

The current environmental moment is dominated by messaging about the importance of animal-mediated pollination in response to the recent, alarming pollinator declines. Contributing factors include habitat loss, agriculture chemicals, and disease, and affect honeybees and native pollinators alike. One of the most common “calls to action” included in such messaging encourages the creation of pollinator-friendly gardens. These spaces are intended to support the foraging and nesting needs of pollinators, but differ from ecological restoration in that they are marketed to homeowners, schools, and parks as a managed, attractive landscape.

Bumble bee on foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis) in Nativars research garden at Jefferson Middle School (Waukgean, IL).

Given their shared evolutionary history, native plants are promoted as a key ingredient of pollinator gardens, especially those designed to support native pollinators. However, the popularity and wide availability of cultivated varieties (cultivars) of native plants can be a stumbling block in plant purchasing and garden design. Often, cultivars of natives are labeled as “native plants,” despite the fact that they can differ substantially from the true native. Cultivars can vary in flower color, size, and scent, as well as bloom time, all traits directly related to attractiveness to and use by pollinators. This begs the question, what is the role of cultivars of natives, or nativars, in pollinator habitat creation? To answer that question, we need to know if nativars provide the same pollinator support as true native plants.

Our partner nursery, Lurvey Landscape Supply (Des Plaines, IL), shares an informational display about the Nativars research project.

Previous Nativars Research

Research to date on this question has been limited in geographic, taxonomic, and temporal scope. The dissertation of Annie White (2016, University of Vermont) focused on 12 native herbaceous plant species and 14 native cultivars, tracking pollinator visitation in field experiments at two sites over two years. Her results found seven native species were visited significantly more frequently by pollinators than their cultivars, four were visited equally, and in only one case was a cultivar visited more frequently than the native species. Similar investigations are underway at the Mt. Cuba Center, including one considering Coreopsis (5 native species, 20 cultivars; Cass & Delaney, 2014) and another on Phlox (6 native species, 2 subspecies, 15 cultivars; Nevison, 2016). The Phlox study found that insect visitation did not significantly differ between cultivars and the straight species in the majority of cases. However, certain cultivars, particularly those selected from the wild, may be more attractive to insects than the straight species. For more information on Mt. Cuba’s trials check out https://mtcubacenter.org/research/trial-garden/.

Enter: Citizen Scientists

Given that one major application of this area of research is to inform home gardeners interested in supporting pollinators, the Budburst team at Chicago Botanic Garden thought this question was a great opportunity to engage the public in a research investigation. We decided to leverage citizen science to elevate pollinator-friendly gardens to pollinator research gardens and gather data on pollinator preferences across the country. To that end, Budburst launched the Nativars Research Project in 2018, bringing together home gardeners, schools, and botanic gardens to collect data on this critical question.

Participants are asked to plant at least one native species and one cultivar from the plant list for their region and conduct pollinator observations weekly during the flowering period. Data can be collected using paper data sheets and entered online via a Budburst account. Our mobile-responsive website also allows you to directly submit observations from a mobile device. Plant lists were developed based on the three hubs for the project: Chicago Botanic Garden, Denver Botanic Gardens, and San Diego Botanic Garden.

Shown here is a subset of the native plants and cultivars evaluated as part of the Nativars research project in the Midwest. From top to bottom: red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia fulgida), New England aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae).

In the Chicago region, Budburst has collaborated with the Chicago and Waukegan School Districts to weave the Nativars research project into life sciences curriculum for students in grades 2-8. Each participating school installs a Nativars research garden and observes pollinators as part of a two-week unit covering the form and function of plants and animals, as well as human impacts on the environment.

A class at Clark Elementary School (Waukegan, IL) poses with their newly installed Nativars research garden.

Early Results: Native Plants Are in the Lead

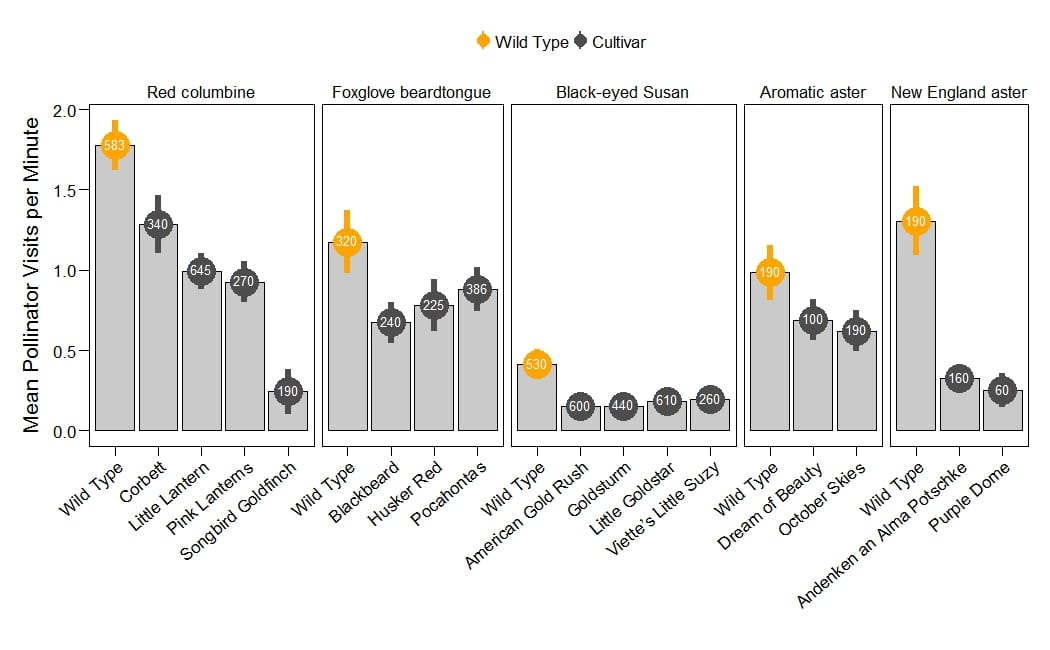

While we have not yet conducted a formal statistical analysis, data for the Midwest plants indicate that mean pollinator visits per minute are higher for true native plants than for their cultivars. However, we also see considerable variation among cultivars, which is not always consistent with our expectation that the greater the degree of trait divergence from the native the greater the impact on pollinator visitation. For example, for red columbine, the most visited cultivar, ‘Corbett’ (1.29 visits/minute), has yellow flowers, yet received more visits than the pink and red cultivars considered. However, the other yellow cultivar evaluated, ‘Songbird Goldfinch,’ was visited the least (0.24 visits/min.). In the case of black-eyed Susan, all cultivars received roughly equivalent pollinator visits (0.15-0.2 visits/min.), at less than half the rate of the true native (0.41 visits/min.). The most dramatic results thus far are for New England aster, for which we see the native (1.3 visits/min.) visited by pollinators at four times the rate of the cultivars (0.25-0.33 visits/min.).

Mean number of pollinator visits per minute to native plants and their cultivars. Numbers within point indicate the number of observation minutes per taxon. Error bars represent 1 SE.

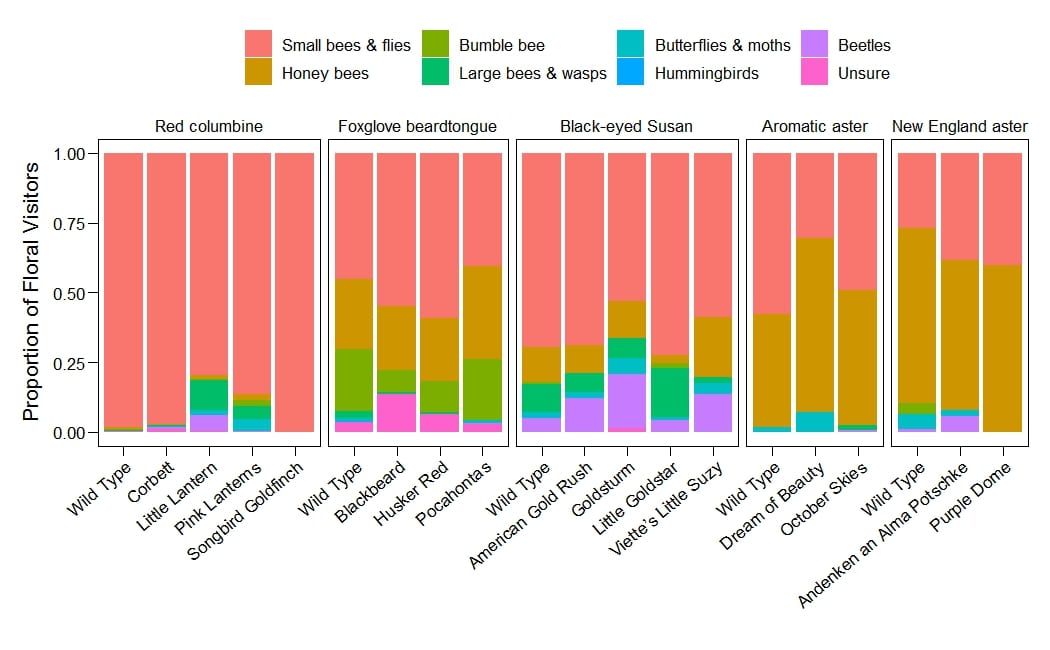

Another expected result was variation in the composition of the floral visitors between native plants and their cultivars due to floral trait manipulation. However, the composition of the floral visitors is largely similar between native plants and their cultivars (Fig. 6). Across all study taxa, the most frequent floral visitors are small bees and flies and honeybees. Importantly, we do see some instances where the diversity of floral visitors varies, for example between the wild type New England aster (4 pollinator groups observed) and ‘Purple Dome’ (2 groups). Oppositely, ‘Little Lantern’ and ‘Pink Lanterns’ attracted a greater diversity of pollinators (5 groups) than the wild type red columbine (2 groups).

Join Budburst Nativars!

While these early results provide interesting insights, with some evidence to suggest that cultivars may not provide equal support for pollinators as true native plants, more data is required before we can draw robust conclusions. Consider joining the Nativars research project to contribute vital data that will help us answer a critical question in pollinator conservation! If any of the study taxa are already a part of your landscape, all you have to do is learn the observation protocol and dedicate 10 minutes a week. Otherwise, contact your local nursery for plant availability. In 2021, Budburst will undertake a thorough analysis of all submitted data, which we hope will bring greater clarity as to the role of cultivars in ecological landscapes.

Sign up for our newsletter. And, follow Budburst on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter @pbudburst

References

White, Annie, “From Nursery to Nature: Evaluating Native Herbaceous Flowering Plants Versus Native Cultivars for Pollinator Habitat Restoration” (2016). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 626. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/626

Cass, Owen & Delaney, Deborah. (2014). Evaluating the attractiveness of Coreopsis (Coreopsis spp.) wild types and cultivars to pollinators. Conference Paper, Entomological Society of America Annual Meeting. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267880051_Evaluating_the_attractiveness_of_Coreopsis_Coreopsis_spp_wild_types_and_cultivars_to_pollinators

Nevison, Keith, “Considering a role for native plant cultivars in ecological landscape: An experiment evaluating insect preferences and nectar forage values of Phlox species vs. its cultivars” (2016). Master of Science Public Horticulture, University of Delaware. http://udspace.udel.edu/bitstream/handle/19716/21442/2016_NevisonKeith_MS.pdf

About the Author

Jessamine (Jessa) Finch is the manager of Budburst, a citizen science project of the Chicago Botanic Garden. She recently completed her PhD in the joint Program in Plant Biology and Conservation of Northwestern University and Chicago Botanic Garden. She is interested in plant conservation, with a focus on the impact of climate change on native plants.

Editor’s Note

Wherever you live, it doesn’t take long to become a contributor to the Budburst project. Once you are set up, you make observations for 10 minutes, once a week. Find a complete overview here.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.