Early on a bright day in April, a diverse group gathered in Providence, Rhode Island in one of the most urban areas of the city – the Manton Heights public housing residences. Winding their way to a rear corner of the complex were staff from the environmental organization Groundwork Providence, driving a truck filled with plants, trees from their urban forestry program, gravel, compost, and shovels.

The day before the installation, the site was prepared by DigSafe and Gates, Leighton. Plants to be relocated were tagged and the garden outline marked.

An enthusiastic group of adults from Groundwork’s Sustainable Urban Landscaping Job Training Program followed, clothed for digging in the dirt. Joining them was the city forester with mulch, an ecological landscaper piloting his Bobcat, instructors from the University of Rhode Island (URI) Outreach Center and landscape architects from Gates, Leighton & Associates, a nearby firm in East Providence.

Solving a Stubborn Storm Water Problem

In the sunny, steep corner lot abutting both the Providence Housing Authority’s Manton Heights parking lot and the nearby Woonasquatucket River, previous work by the Gates, Leighton & Associates landscape architects had revealed a stubborn problem. A sloped, planted bank running along a concrete staircase leading from a residence building down to the parking lot could not handle its regular load of storm water. Rain falling on an upper paved area added to the burden causing sheet erosion, flooding, and silt blowouts into the parking lot at the bottom of the bank. And all that water and silt was ending up in a storm drain.

It was a perfect location for a trial installation of a rain garden. Extra motivation came from the fact that in January 2011, Rhode Island instituted one of the most environmentally forward-looking storm water policies in the country. The guidelines stipulate that for all new development, storm water must be handled on site using a variety of practices (including rain gardens) that aim to divert storm water from conventional sewer lines and, instead, stop and infiltrate the water to its native aquifers.

Students Sidney Scott, Ricardo Tillman, and Charlie Brown (left to right) placed fiber logs to protect parking lot drains from stockpiled loam.

Real-life Experience

At the same time, Groundwork Providence, whose environmental job training programs are designed to help low-income and underserved populations develop the career skills needed to gain employment as stewards of their own environment, was approaching the end of their spring cycle of job training. The URI instructors and Gates Leighton landscape architects had all been involved in the curriculum, teaching the portions of the courses involving storm water management best practices, native plant selection, and urban landscape design. After learning the “whys” of ecological landscaping practices, the students were eager to get some practice with the “hows” of the field. The students sought a real-life experience installing a rain garden, and Manton Heights offered itself.

Dave Renzi of Out in Front Horticulture used the Bobcat to place two boulder clusters to visually define the garden extents.

Both the instructors and the students were aware that gaining experience by implementing a storm water practice such as a rain garden the “right way” – in other words an installation that is both beautiful and functional – would give them a great advantage in terms of the quality of their training and their job readiness post-graduation. Many landscape practitioners have found, in making the switch to environmentally sustainable practices, that it is not only the designers who must overcome a steep learning curve in order to change their conventional ideas about storm water engineering.

Left to right: Charlie Brown, Sidney Scott, Joe Vaughan, Sheri Lupoli, Linda Barros, Armindo Timas, Jordan Lucas, Ricardo Tillman, and Nyemelah Jacob finish up fine grading and sculpting of the forebay trench.

Installation teams also need to understand how to make the switch from conventional to innovative construction practices. Ecological designers are eagerly attending workshops, tours, and presentations on rain gardens, native plant selection and composting, just to name a few. As these ideas become mainstream, designers are readily able to convince clients to accept ecologically-based landscaping principles. But translating these new design ideas into tangible landscape is the job of the landscape contractor and her team. If each worker on the team knows how and why these new methods need to be carried out, they not only gain an advantage in the competitive job market, they also contribute to ecological sustainability in a very real way.

Kate Venturini, Ricardo Tillman, Jordan Lucas, Joe Vaughan, Armindo Timas, Charlie Brown, Alfred Elliot, and Sidney Scott spread the planting medium.

Locating the Garden

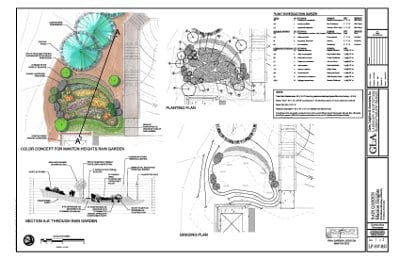

In their class earlier that April week, the students had been given a package of construction drawings for the rain garden which had already been designed by Gates, Leighton & Associates. Already very familiar with the concept of rain gardens, the students arrived at the site with the drawings and assessed the staked and painted biomorphic shape of the future garden to be installed at the bottom of the troublesome slope.

Plants are placed by (foreground) Charlie Brown, Sidney Scott, (background) Armindo Timas, Jordan Lucas, and Nyemelah Jacob.

They pinpointed locations for a 2-foot-wide grass infiltration strip along the garden edge where water was to enter and for a flanking infiltration trench of pea gravel which would serve as the “treatment forebay” before water entered the garden bowl itself. On the garden edge closest to the parking lot, the plan’s instruction was to create a curved berm which would prevent water overtopping the garden. The students grabbed shovels and dug in.

As the day progressed, volunteer Dave Renzi of Out in Front Horticulture took over the digging with his Bobcat and then clustered four one-ton landscape boulders at the garden’s edge – an aesthetic touch also serving to bolster the garden sides. Groundwork Providence’s Director of Education, Sheri Lupoli, and Executive Director Joe Vaughn, shoveled gravel into wheelbarrows which were then transported by the students and poured into the infiltration forebay.

Sidney Scott and Nyemelah Jacob wheel mulch while Sheri Lupoli, Joe Vaughan and Kate Venturini wait for the next wheelbarrow.

URI Outreach instructor Kate Venturini assisted students with selecting and placing native perennials that had been donated by the Groden Center, a vocational program for individuals with autism, and by Briden Nursery of Rhode Island. Ray Perreault, Groundwork Providence’s Director of the Trees 2020 Program, oversaw and instructed students in proper placement and planting of native tree species. The job of hauling the garden’s mixed-to-spec sandy loam and mulch…and more mulch, and then still more mulch…fell to landscape architects Art Eddy and Amanda Sloan. Mulch, in fact, is considered to be an important part of the filtration system of a rain garden.

Janay McKinney and Armindo Timas stabilize the retaining berm with wood chips. Later in the season clover and grasses will begin to colonize the berm.

A Community Engaged

As work continued through the afternoon, two film crews showed up and the students became stars. Environmental Protection Agency environmental planner Myra Schwartz and website manager Cindy Brown were filming a series of educational videos on green practices and had been tipped off that the garden was being built that day. Reporter Sejal Lanterman of NBC TV Channel 10’s “Plant Pro” series was featuring green gardening practices on her show the following week. The students were interviewed, proving knowledgeable and comfortable with rain garden design and construction.

Three months after installation, sisters and Manton Heights residents Niurka and Nicole helped freshen the garden mulch and then agreed to pose for a photo with a watering can, even though the garden needs no irrigation at this point!

As the sun began to lower behind the buildings, Manton Heights’ residents and their children began returning home from work and school. Especially appreciative of the new garden, the children clustered around and volunteered to help with the planting. Grass seed was cast and plants were watered by these additional late afternoon workers.

A view of the forebay features of the garden: a stone trench (peastone lies under the larger stone) and a grass filter strip.

Measuring Success

Visits to the garden since have shown that it is functioning well. It is capturing and filtrating storm water with no overflow into the parking lot. Structurally, the grass and gravel infiltration forebay is holding up but will need some “tweaking” to help it avoid collecting mulch. As for that other ideal rain garden parameter: beauty? Look at the photos and – bearing in mind these are first year plants – judge for yourself!

NOTE: This rain garden is constructed and dimensioned adhering strictly to the standards outlined in the new Rhode Island Storm Water Design and Installation Standards Manual. See the accompanying Gates, Leighton & Associates detail drawings. Most of the professionals named in this article are members of the Ecological Landscape Alliance and the Rhode Island Nursery and Landscape Association.

About the Author

Amanda Sloan has drawn upon her background in environmental science, community design, and art during fifteen years as a landscape designer on a wide variety of projects, including school and playground gardens, lakeside parks, municipal recreation sites, commercial, public, and residential landscapes. Currently a landscape designer at Gates, Leighton & Associates Landscape Architecture, Inc., Ms. Sloan qualified in spring 2011 to become a licensed landscape architect in Rhode Island. At GLA she works on parks, conservation developments, residential design, and planting design throughout New England and assists with presentation graphics and writing. She achieved certification by the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council in Invasive Plant Management and teaches landscape design and low impact design techniques through Groundwork Providence. Amanda may be reached at asloan@glala.com.

Amanda Sloan has drawn upon her background in environmental science, community design, and art during fifteen years as a landscape designer on a wide variety of projects, including school and playground gardens, lakeside parks, municipal recreation sites, commercial, public, and residential landscapes. Currently a landscape designer at Gates, Leighton & Associates Landscape Architecture, Inc., Ms. Sloan qualified in spring 2011 to become a licensed landscape architect in Rhode Island. At GLA she works on parks, conservation developments, residential design, and planting design throughout New England and assists with presentation graphics and writing. She achieved certification by the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council in Invasive Plant Management and teaches landscape design and low impact design techniques through Groundwork Providence. Amanda may be reached at asloan@glala.com.