by Eloise Gayer

While the Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania is well known for its veteran trees, horticultural displays, and exciting garden features like the fountains and Ferny, the Arboretum also has many acres of dedicated natural areas where native plants and wildlife reign. In 2001, the Arboretum conducted a restoration project to return an area of drained wetland on the property to its original form. This wetland has been a source of calm, sanctuary, and connection to nature for me during my time here at the Arboretum. I spend the majority of my time in the Rose Garden – the most aesthetic, heavily cultivated area of the Arboretum – so I am always eager to visit parts of the Arboretum that are a little wilder. In this article, I explore the history of the wetland, its ecological function, and its value to the public garden.

As part of John and Lydia Morris’s private estate, the area was actively farmed from 1892, when the land was purchased, until the end of WWII. Around 1907, terra-cotta drainage tiles were installed to drain the low floodplains directly into the Wissahickon Creek, creating space for crops to grow or cattle to graze. In the 1930s, the farm was used to raise beef to support the war effort. By this time, the Arboretum had already been established as a public garden, and the land was leased out to local farmers. After WWII, the area was converted into meadows through which the visitor could walk and enjoy a quiet, naturalistic setting. In 2001, the Pennsylvania DCNR and the Pennsylvania DEP approached the Arboretum with funding for a wetlands restoration project in Philadelphia. With no other former wetland sites within the city limits to be found, the Arboretum was the perfect recipient of this restoration funding, and thus the next generation of wetlands were born.

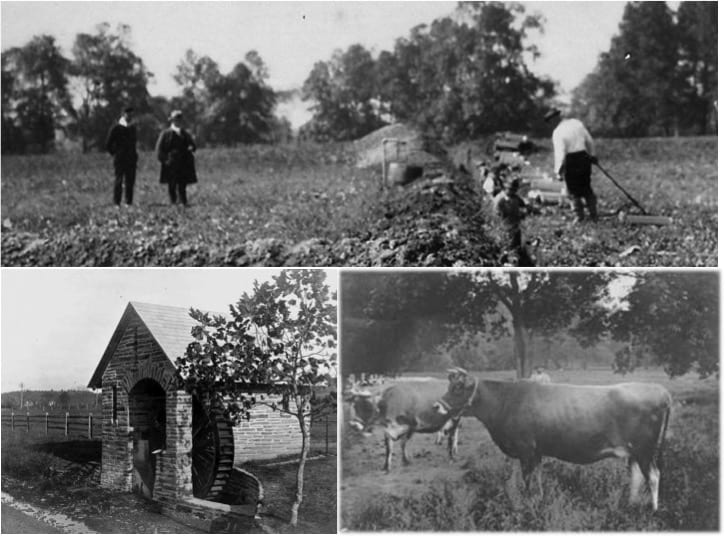

The wetland area circa 1907. The above image shows the drainage tiles being installed. The Pump House (lower left)was used to pump water into troughs for the cattle(lower right). Photos from the Morris Arboretum archives.

To reinstall the wetlands, the Arboretum contracted Pam Morris Olshefski from the Delaware River Keepers, who was already working at the Arboretum on a stream restoration project. As of January 2020, she is the horticulturist in charge of the Morris Arboretum’s Natural Areas and manages the wetlands she helped create almost twenty years ago. As we walked around the wetlands, she described the design and installation process, and some of the challenges faced by this particular site.

One noteworthy challenge was the presence of Galega officinalis or goat’s-rue. This federally listed noxious weed escaped from the nearby Mount Saint Joseph Academy where it was part of a collection of plants with significant religious iconography. Because it is mildly poisonous to cattle, anybody who finds it on their property is obligated to control it. Unfortunately, goat’s-rue seeds can remain dormant in the soil for up to 30 years, making its control very difficult. To prevent its spread, all the soil removed from the wetland area had to remain on-site and was repurposed to create berms, hummocks, or islands. All vehicles had to be hosed off and disinfected at the end of each day’s work.

The entire construction of the wetlands’ landscape took several weeks, but it took only two days for the water to fill the pond after the drainage tiles were broken. It was plain to see that the area was being returned to the natural state at which the hydrology, geology, and plant life in the area hinted. During construction, the Botany Department at the Morris Arboretum developed a plant list based on observations at nearby wetland sites with similar geology: where limestone meets an acidic quartzite ridge. The sites surveyed were the Quakertown Swamp (partially controlled by PA State Game Lands, partially private) and a wooded wetland near Holicong Road in Buckingham Township. The Arboretum’s botanists also inventoried plants along the Wissahickon Creek between Montgomery County and the Arboretum, invasives included. By doing so, they were able to predict what invasive plants may present an issue in the future of the wetlands. The following spring, the Arboretum’s staff, volunteers, and a group from the EPA installed native trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants along the borders of the freshly filled wetland.

A blue heron in the wetlands as they appear today. Photo by Pam Morris Olshefski.

The goals of the wetland reinstallation project were threefold: 1) to create an effective stormwater management system to protect the Arboretum against severe weather events, 2) to create a functioning wetland ecosystem to encourage biodiversity and, 3) to create a beautiful and educational opportunity for visitors to learn about the importance of wetlands in the environment.

To assess if the first goal has been met, one needs only to look at the system and see if it is still functioning after twenty years of use. A permeable parking lot at the top of the property’s slope serves as the first line of defense during weather events; drains along the main driveway direct runoff water in the first of three connected silt basins that eventually lead to the wetlands; the plants within the wetlands filter the water as their roots absorb impurities. The result is a sustainable system that invites as much water as possible to remain in the wetland until it slowly filters into the Wissahickon Creek.

Bird species spotted at the Arboretum’s wetland. Clockwise from top: Eastern bluebird, Pileated woodpecker, Baltimore oriole. Photos by Bob Gutowski.

The Arboretum uses the diversity of bird species present in the ecosystem as biological indicators of the success of its restoration. Birds rely on the presence of fish and insects, which in turn rely on healthy plant life; thus the number of bird species present in the wetland represents the success of the entire ecosystem. According to ongoing citizen science efforts to document bird species in the wetland, more than 160 species have been sighted. The Arboretum’s wetland is considered a Hot Spot for bird activity, according to Cornell University’s eBird website.

The Morris Arboretum has a robust education department, and the wetland has been successfully integrated into classes for all ages, summer camps, and informational tours. Because of its diverse visitorship and programming, the Arboretum is equipped to reach a wide audience. Although the wetlands have provided many educational opportunities already, Pam hopes to expand the wetlands’ educational agenda even further and to inspire a new generation of ecological stewards for the future. After twenty years of dutiful management, all three goals of the reinstallation project continue to be successfully met, with plans in place to expand the wetlands’ benefits to the public and the ecosystem even further.

Birding class in the Morris Arboretum’s wetlands. Photos by Bob Gutowski.

Oftentimes, wetland mitigation projects fail because of the site conditions in which the wetland was installed, or because they are not actively managed after their installation. In the case of the Morris Arboretum, the wetlands continue to thrive as Pam (and the previous Natural Lands Managers) raise and lower water levels to control water temperature and encourage migratory birds, remove invasive species, install native plants, and create innovative programming to ensure public support. Given its success in supportive staff, dedicated volunteers, and informed management techniques, the wetland provides an excellent model for future restoration projects seeking to broaden species diversity, create educational opportunities, and enrich the environment with diverse ecosystems. This wetland is an excellent model for other wetlands of its kind, relying on supportive staff, dedicated volunteers, and informed management techniques to create beauty, species diversity, and educational opportunities.

Reflection of autumn colors in the wetlands. Photo by Bob Gutowski.

About the Author

Eloise Gayer is an intern at the Morris Arboretum, where she is developing her horticulture, plant identification, and design skills within the Arboretum’s rigorous training program. Her internship focuses on the Rose Garden, and she is always searching for ways to integrate ecologically minded horticultural practices into this historic space. Following her internship, she will join the field staff of Rushton Farms in Newton Square, PA, home of the Community Supported Agriculture program within the Willistown Conservation Trust. She is a longtime gardener, reader and writer of fiction, and collector and propagator of succulents and tropical houseplants.