by Lisa Cowan

Recent destructive storm events have focused public attention on climate change, sustainable site design, and resiliency. As ecological design practitioners, we have an opportunity to build on this paradigm shift and take the lead in promoting a more sustainable approach to water management. To help our new ideas take root quickly, we must bring together new ways to frame our discussion of ecologically-based design, and we must follow through with beautiful spaces that resonate.

When the general public first started to talk about managing stormwater, many jumped on simple solutions. I heard one well-meaning municipal official suggest a rebate system for individual homeowners who installed rain barrels; another suggested that tree box filters would be the panacea for downtowns; others discussed the potential for rain gardens.

Searching for Workable Solutions

Fast forward to Hurricanes Irene and Sandy, which helped bring home the realization that climate change and stormwater management are beyond these small measures. The conversation about rain barrels and residential rain gardens has evolved to encompass more meaningful ways of managing stormwater, including using green infrastructure, permeable pavements, whole scale lawn replacement, and green roofs.

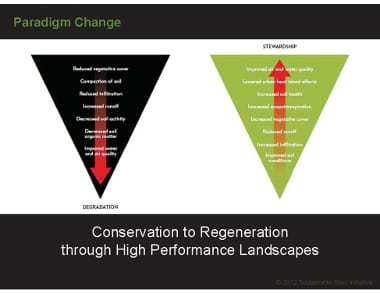

One bright note among these recent natural catastrophes is that people are much more willing to engage in understanding the problem and discussing potential solutions. However, our old arguments, for the most part, don’t work. We need to drive the conversation in ways that help people relate it to their own frame of reference. Here are two concepts that I have found to be the most successful in that conversation: the role of “Ecosystem Services” and talking about greenspaces as “High Performance Landscapes”.

New Concepts Change the Conversation

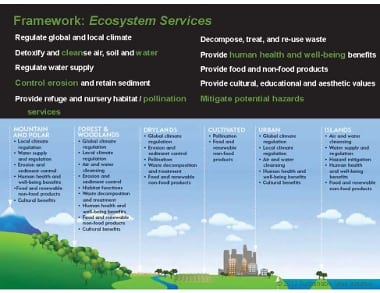

Ecosystem Services, as defined by Wikipedia, are the collective resources and processes supplied by nature from which humankind benefits. These benefits include products like clean drinking water and processes such as the decomposition of wastes. The United Nations formally defined the four broad categories of these services in its 2005 study, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment:

- Provisioning, such as the production of food and water;

- Regulating, such as the control of climate and disease;

- Supporting, such as nutrient cycles and crop pollination; and

- Cultural, such as spiritual and recreational benefits.

I first encountered the concept of “High Performance Landscapes” through my outreach work with the Sustainable Sites Initiative (www.sustainablesites.org), and its value stood out to me immediately. The term “high performance buildings” is part of the LEED vernacular, and therefore is understood – or at least appreciated – by most people. And the term “performance” brings home that outdoor spaces provide real, meaningful functions even in small spaces.

The great news for ecological practitioners is that High Performance Landscapes have the potential to go even further than high performance buildings. While a high performance building strives for NetZero impact, a High Performance Landscape can positively impact Ecosystem Services by provisioning, regulating, supporting, and providing cultural benefits to society.

The way to change the conversation about stormwater management is to use these terms as a framework for your outreach efforts with potential partners, including clients, community members, municipal officials, and local environmental organizations. As they embrace the benefits of enhancing ecosystem services, they will see that ecological design is more than a feel-good approach – it has the potential to provide multiple benefits that we all value (clean water, pollination for food production, temperature regulation, to name a few).

Remember to “Design” Ecologically

In your outreach efforts, it is important to remember that the idea of ecologically based design is relatively new to most people. While they may have a positive reference image in mind, the reverse is equally possible. Some may associate ecological design with negative images, including “messy” designs, those that lack order, or are just plain ugly. If we want people to embrace more ecological solutions for water management, we must find ways to directly link design and aesthetics to our ecological approach, and we must take the time to make our projects resonate.

The photo below shows an example from my local community. Several years ago, several state and local agencies got together with a couple of high-profile engineering and construction firms to create a model bioretention demonstration project in a highly visible location close to our office. The motives and goals were good – the intent was to show people how green infrastructure can work as an alternative for stormwater infiltration and treatment. Unfortunately the design, aesthetics, and the performance of the plants looked like they were an afterthought. This was the result.

A missed opportunity, this model bioretention demonstration project failed the aesthetics test. Photo by Lisa Cowan.

The opportunity to create a beautiful and meaningful project that resonated with the public was lost. To make matters worse, as time went on, plants were stolen, which further denigrated the installation.

We all can point to similar projects where good design and aesthetics took a back seat to ecological performance. We can complain all we want that people “just don’t get it,” but until we make the design as compelling as the performance in our ecological projects, we will continue to practice as second-class professionals.

Good Design Includes Beauty

Lance Hosey, the chief sustainability officer at RTKL, and author of The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology and Design, demonstrates the importance of good design and aesthetics in a New York Times opinion piece (2/15/2013) titled “Why We Love Beautiful Things,” http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/17/opinion/sunday/why-we-love-beautiful-things.html?_r=0. He notes that color (shades of green) can boost creativity and motivation. Natural fractals (irregular, self- similar geometric forms and shapes) that occur throughout nature have universal appeal to humans. We also respond quickly and positively to the shapes that mimic the “golden rectangle.” In short, good design and aesthetics matter.

Humans connect with visually appealing designs such as the natural fractals in this frozen puddle. Photo by Lisa Cowan.

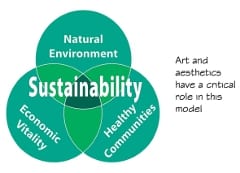

People often equate aesthetics with luxury, but if a design is not beautiful, it is not sustainable. For the public to embrace an ecological or sustainable design, it must be aesthetically pleasing. Beauty is subjective, but a good design addresses aesthetics with meaning and intent. For example, a natural meadow or wetland might be gorgeous in a rural context, but would probably look like a weedy mess in an urban lot.

We need a new, two-pronged approach toward engaging our stakeholders on stormwater management and other ecological designs. First, we need to find new ways to frame the conversation, and then we must follow through with designs that create beautiful spaces that people can connect with. The sooner we start on this path, the sooner our ideas can take hold.

About the Author

Lisa Cowan, PLA, Principal, Studioverde, is an Officer in the American Society of Landscape Architects Sustainable Design and Development Professional Practice Network. Her work exemplifies a lifelong interest in the restoration of natural systems and community engagement in the natural world. Lisa was the lead Landscape Architect for more than 30 successful ecological restoration projects that focused on water management. Lisa’s extensive background in ecology-based planning, design, implementation, maintenance, and monitoring informs her work with clients to achieve their sustainability goals for their properties, campuses, and communities. She may be reached at lcowan@studioverdelandscape.com.

Lisa Cowan and Heather Heimarck , ASLA, MLA, and Director of The Landscape Institute at the Boston Architectural College, contribute articles to an occasional series that examines water from a variety of perspectives and aesthetics while referring to different regulatory, technological, and design approaches.