by Rachel Lindsay

In my work, I find the act of caring for the land and caring for the people who are engaging with the land intricately woven together. My first jobs were working in special education and at organic vegetable farms. When I needed guidance in which direction to take a career, I spent a year working at a Camphill Community. Camphill is a worldwide social initiative of communities designed to include people with and without intellectual disabilities. Every village is centered around a working biodynamic farm. Taking care of the houses, farm, landscape, and people provides meaningful work for everyone, inclusive of all ranges of physical or cognitive ability. As a landscape designer over a decade after these formative experiences, my most meaningful projects are the ones that work at the intersection of human and ecological health.

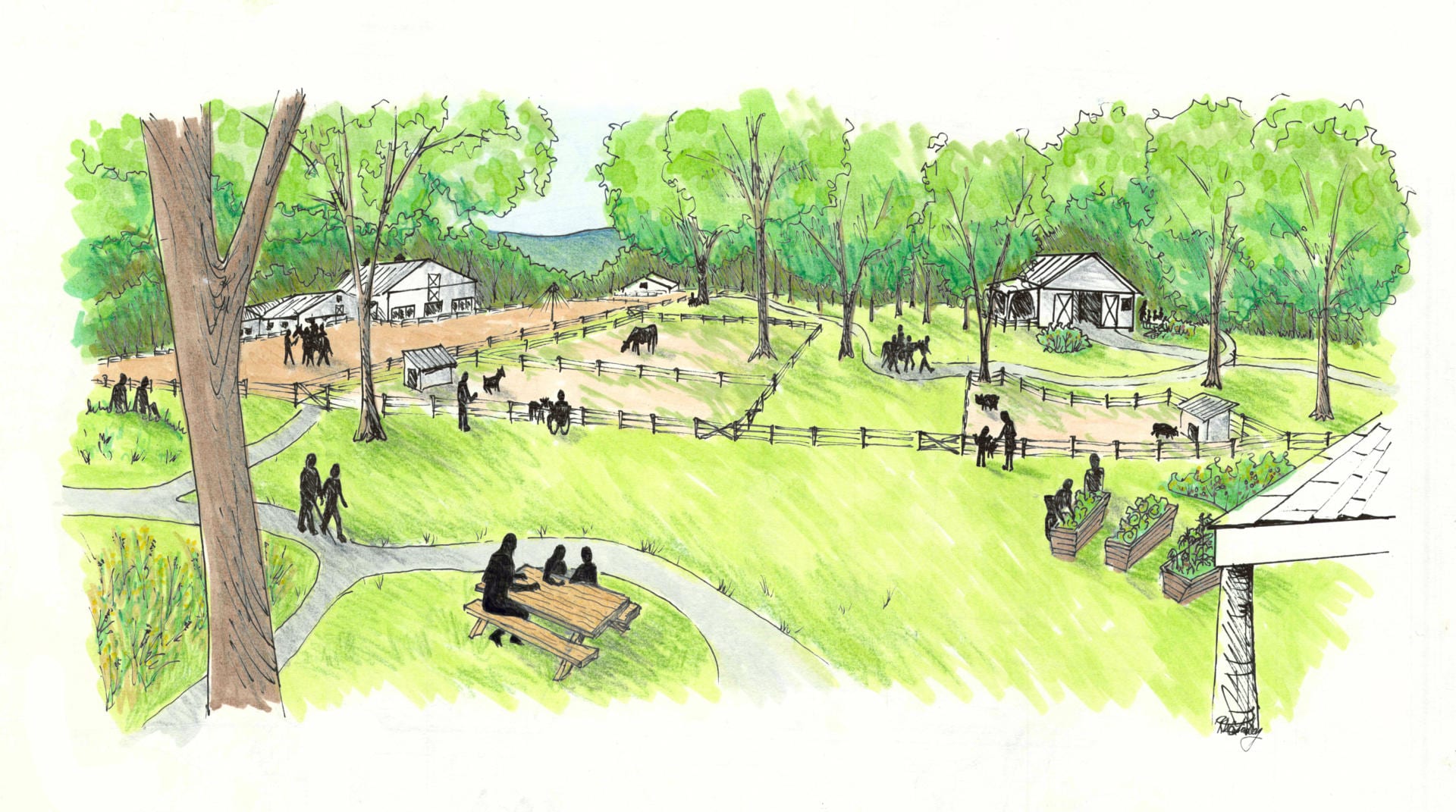

When we are designing landscapes intended for people to engage with them, both the design process and the physical elements included will affect who will benefit, and how. The following material was developed mainly through the design of a master plan and five-acre therapeutic vegetable farm for Pony Power Therapies, a non-profit therapeutic riding center, however many of the design considerations and tools would be just as applicable to other kinds of gardens.

The vision for the campus Master Plan at Pony Power Therapies included accessible gardening and recreational spaces integrated with animal paddocks, pollinator habitat, and rain gardens and detention ponds for stormwater runoff. Image Credit: Regenerative Design Group

Guidelines vs. Standards

The first step in ensuring the accessibility of a space is to review or decide during the initial planning process what standards and guidelines should apply to the project. Public and commercial projects will be required to follow standards set by the local government agency or municipality. Most municipalities and agencies adopt standards set by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) for public and commercial buildings, but in some cases they may differ. Standards are enforceable; guidelines like those published by the ADA become enforceable only when they are accepted as standards by a regulatory agency.

The US Forest Service has published its own guidelines for designing spaces for outdoor recreation and trail design and construction. These have been adopted as standards for any section of a National Park labeled “accessible.” These published guidelines are great resources for projects even if following specific standards isn’t required.

Universal design is a non-regulatory term that I find helpful to consider in the initial concept stage of a project. It is a design approach that attempts to provide the same or equivalent access or experiences for the widest group of people possible. Originally applied to architecture, it is just as applicable to landscapes. Especially for public and participatory gardens, good design will take into consideration the quality of experiences for people with a range of physical abilities. It is possible for a space to meet the required accessibility standards, and yet provide a far inferior experience for a person who uses a wheelchair. Universal design stretches us as designers to not only apply accessibility criteria provided by regulatory agencies but also provide the highest value of experience possible for all participants.

My local public library, in a historic building, met accessibility standards by creating a rear entrance with ramps. While it may meet code, the experience of entering through the barren, utilitarian rear is far inferior to entering through the front door flanked with beautiful gardens directly into the lobby. Plans for a new library in Greenfield apply a Universal Design approach and include one main entrance that will be accessible to everyone. Image Credit: author

A universal design approach can be expressed in the goals of a project, and in the design criteria. For example, a goal for a community or school garden might be to distribute accessible elements throughout the space to avoid a situation where one participant would be relegated to the same part of the garden on every occasion. By providing choices in how people with different abilities engage with the land, we can help create equivalent experiences where equal ones are not possible.

As ecological designers, we take the concept of universal design even farther. How can this landscape be beneficial not just to people of all abilities, but also to wildlife, pollinators, soil microorganisms, and watersheds? Addressing a diversity of people’s physical needs in a landscape dovetails with our practice of considering a diversity of habitats and functions for ecological landscapes.

Structural Considerations

There are a myriad of designs and resources available for designing accessible outdoor spaces and gardens. Just as a high diversity of species will increase the ecological resiliency of a garden, a higher diversity of design elements will increase the number of people who can participate in and benefit from a garden. For gardens intended to produce food, the seasonal shift of tasks and structures of the plants are best accommodated in a range of growing environments that can also be intentionally designed to increase the accessibility of the gardening tasks for a diverse group of gardeners.

Bed Height

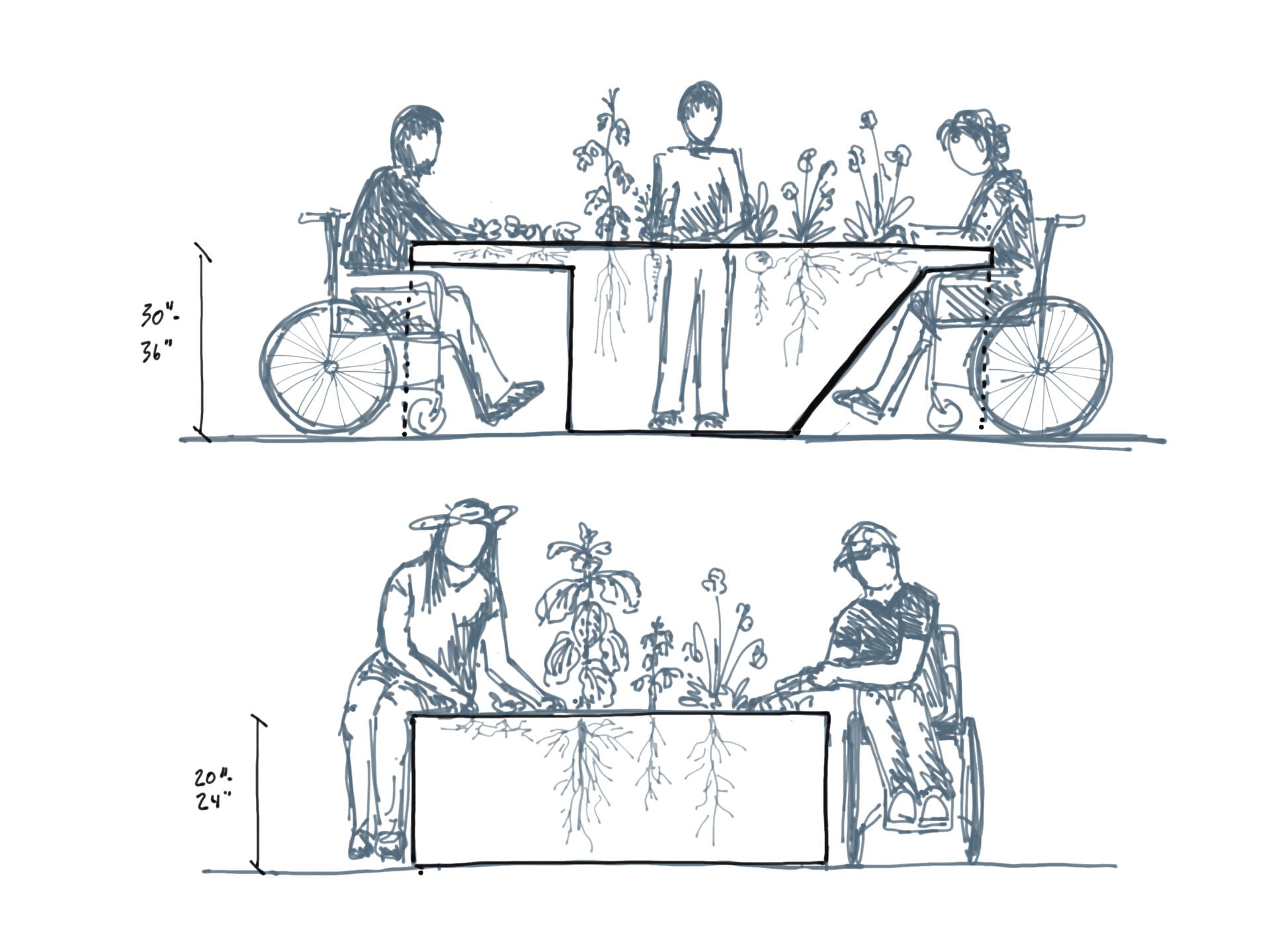

A raised bed that is a good height for some people to sit and garden at might also be the perfect height for others to use as a standing bed. Image credit: Regenerative Design Group

Two ways a gardener might sit while they work are beside a garden by turning to work sideways, or facing a garden, either leaning forward or at a table-type raised bed that has space underneath for their legs. To work comfortably sitting forward, the bed height should be around 30-36 inches tall. Beds this tall are also well suited for standing and working without bending over.

For planting tables designed to be worked while facing forward, the space underneath should be at least 28 inches high. That leaves only 6-8 inches of space for soil – and plants that grow taller than 12”-18” will soon be out of reach for a seated gardener. These types of beds are best suited for herbs and greens or low growing perennials like strawberries and shorter flowers.

No one raised bed fits all people or plant types. Consider integrating beds of different types that can be worked at from different orientations. Beds with sloped sides can accommodate sitting gardeners and contain more soil for healthy root growth than planting tables can. Sketch by the author.

To work sideways, even raising a bed just 12” can make a difference for someone reaching from a stool or a wheelchair. Beds that are 20”-30” may be more comfortably weeded from a sitting position for a longer period of time than taller beds, and may accommodate taller plants. Working sideways requires a seated gardener to twist – an action that might be a good stretch for some, and uncomfortable over time for others. Integrating beds of varying heights offers the opportunity for some gardeners to alternate sitting and standing while working, and choose positions that offer the right amount of stretch for them.

Often seen as an accessibility challenge, a sloped area might be used to an advantage by creating terraced beds on contour that have different heights on the uphill and downhill side. As the plants in the beds grow throughout the season, gardeners might find that the side of the bed they find most comfortable to work at changes. Trellised vegetables or fruit trees integrated into terraced beds might be accessible from one side of the terrace at planting, and the other at harvest.

The vegetable gardens at Greenfield Community College’s Outdoor Learning Lab featured terrace beds where gardeners can work together on the same plots while seated or kneeling at ground level. The gardens, which also include a wetland, small orchard, and pollinator meadow, were designed by Arkose, a collaboration between Regenerative Design Group and Kim Erslev of Salmon Falls Design. Image Credit: Regenerative Design Group

Vertical Growing

Trellises and green walls are a low-investment way to add accessibility to people of varying heights. Locating trellises at the edge of beds and gardening spaces rather than in the middle increases their accessibility by making them easier to reach.

There are numerous vertical garden designs, many of which use recycled materials and can increase the growing potential for small sites. Most designs only accommodate a small volume of soil, and so plants with small root masses are more likely to thrive in them. They often dry out quickly as well, so incorporating an irrigation system will increase their success.

Paths

Stone Dust meets ADA guidelines for accessibility and is fairly inexpensive to install and maintain; however, it can become a significant problem at in-ground gardens because the stone dust can migrate into the garden beds. Along raised beds, as shown here at the Fowler Clark Epstein Farm, it is less of a problem. Image credit: Regenerative Design Group

The ADA and US Forest Service guidelines offer good criteria for designing paths with accessible slopes, turning radiuses, and surfaces. For some projects, adding paved surfaces to comply with accessibility requirements comes in direct conflict with stormwater regulations that restrict increasing the amount of impervious surface. Paving large amounts of area in a garden or farm setting also changes the aesthetics of a site dramatically, or could throw a project budget out of reach. Grass pavers and reinforced turf are alternatives we can consider for gardens that provide a sturdy surface and also increase the permeable, vegetated area in a garden. These considerations are all very site specific – high foot traffic or heavy shade might leave the unattractive mats or pavers bare. It is always important to check the specifications of these products; not all reinforced turf mats and grass pavers meet ADA guidelines.

Plant considerations

What do beets have in common with apples? Round, red, and sweet, but botanically – not much! Sowing seeds, weeding, and yanking a beet out of the ground are very different actions than pruning, thinning, and picking apples. Vines, perennial shrubs and trees, root crops, grain crops, and trellised or espaliered fruit require very different management. Piecing together a variety of plant types will increase the opportunities for people to participate during any season, as well as cater to many different tastes.

Extendable handled loppers help give extra leverage and allow you to prune from farther away; garden trowels and rakes with vertical handles can be more comfortable when sitting, and replacing small round spigot handles with ball valves that have straight handles make them easier to operate. Image credits (clockwise starting upper left): Kseibi.com, Arthritissupplies.co, plumbingsupply.com

Tool considerations

Adequate tools can make a world of difference for people learning or stretching themselves to perform precise gardening tasks. Garden carts with two wheels, tool extenders, long-handled loppers, and hand tools with wrist guards or vertical handles are just a few of the tools available that are designed to make working in a garden more accessible and enjoyable for people. A full discussion of specific products and types is the topic for a separate article.

Integrating seating with a trellis or arbor is a nice way to provide support while pruning and harvesting vine crops, and creates an enjoyable space for everyone when the garden work is done. Image Credit: Regenerative Design Group

Gardens Benefit Everyone

Widespread attention on the benefits of gardening has soared during the last few months. Increasingly complicated logistics in the food system has brought the spotlight back to the home garden as a source of food resiliency, while the necessity of staying home to protect us all from the spread of COVID-19 allows more time to garden for many people. Gardening also provides an outlet for physical exercise and has been shown to help relieve acute stress. The benefits of gardening for mental health have been documented by clinical studies. In England, mental health professionals provide patients with prescriptions to participate in community gardens. Clearly, we all benefit from being able to work in our gardens, regardless of physical capabilities. For gardens to provide the greatest benefit to a community, they need to be accessible to as many people as possible. There is no one way to ensure that a garden space offers something for everyone during the full growing season – but applying a clear intention to offer as many people the ability to participate as possible will certainly lead to creative and beautiful solutions.

Resources

Rothert, Gene. 1994. The enabling garden: creating barrier-free gardens. Dallas, Tex: Taylor Pub. Co.

Adil, Janeen R. 2009. Accessible gardening for people with physical disabilities: a guide to methods, tools, and plants. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

Yeomans, Kathleen. 1993. The able gardener: overcoming barriers of age and physical limitations. Vancouver: Whitecap Books.

ADA National Network www.adata.org. The ADA National Network provides information, guidance and training on how to implement the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in order to support the mission of the ADA to “assure equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency for individuals with disabilities.”

AgrAbility www.agrability.org. A consumer-driven USDA-funded program that provides education, assistance, and support to farmers and ranchers with disabilities. AgrAbility program services are provided through state projects and the National AgrAbility Project at Purdue University.

Tetra Society www.tetrasociety.org. Tetra builds innovative solutions for people with physical disabilities to overcome environmental barriers, providing greater independence, quality of life, and inclusion.

About the Author

Rachel Lindsay is an ecological designer, artist, and avid gardener. She draws from her experiences in farming, community development, and art to engage people in the design process. Before studying landscape design, she farmed in New England at several CSA farms and spent six years living and working with Fair Trade agricultural cooperatives in Nicaragua. She holds an MS in Ecological Design from The Conway School and a BA in Anthropology from Wesleyan University. As an Associate Designer at Regenerative Design Group, she works with organizations and home-owners to design and implement productive, resilient landscapes.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.