This excerpt from a longer article is reprinted by permission of the author and Native Plants & Wildlife Gardens and appears in full at http://nativeplantwildlifegarden.com/a-tale-of-three-garden-shows-progress/.

by Sue Reed

I have recently attended three very different garden shows that together reveal a big shift in our society’s gardening attitudes and interests. Yet I also found that a troublesome old belief – the idea that people’s garden dreams are more important than the health of the natural world – not only persists but is being re-invigorated in a surprising new way. …

That revelation came at my third garden show, the Ecological Landscape Alliance’s 18th Annual Conference and Eco-Marketplace. No fancy floral displays here. Just 40 exhibitors and 23 speakers in two educational days, co-sponsored by the Conway School of Landscape Design and the Association of Professional Landscape Designers, oriented toward an audience of 400 professionals with an interest in sustainable landscaping.

I have attended this conference many times in the past because it has always provided tons of useful, cutting-edge information, plus it’s held in Springfield, MA, not too far from my home. Many attendees travel here from quite far away because no other conference in New England offers this particular set of knowledge.

I must now disclose that, thanks to the generosity of the organizers, I was given a press pass to cover this year’s event. Even without that privilege, though, I would honestly report all good things about the ELA conference…with one slight exception, as you’ll see.

The exhibitors were specific to sustainable landscaping: Biochar Northeast, Compostwerks, EcoDepot, New England Wetland Plants, Ocean Organics, the George Washington University Sustainable Landscapes Program, NOFA, etc. Three that stood out for me were:

• Project Native; a small nursery that collects its own seed, raises and sells native plants, helps in local restoration projects, and has grown steadily in size since it began 10 years ago, despite the tough economy.

• Herbanatur (pronounced Er-ba-nay-tchure, not, as I thought, like it rhymes with terminator); a new organic weed-control that is actually a salt, a form of sodium chloride. Used as a foliar spray or root injection, it can kill every major invasive weed I could name, including Japanese knotweed, goutweed, giant hogweed and even buckthorn, supposedly without causing harm. If this is true, it’s impressive. (But could it be true?)

• Groundscapes Express, a company that has devised a product combining compost and partially decomposed shredded wood (NOT wood chips), to bring myccorhyzae filaments and humic acid quickly into play in stopping erosion and enhancing growth of both herbaceous and woody plants.

One of the frustrations of attending an excellent conference like this one is that there’s no way to hear all the interesting talks, many of which run concurrently to satisfy to a wide variety of appetites. Here are just a few significant things I learned in my hopping around:

• Big storms associated with climate change are going to transport a lot of species to new ecosystems. For example, Hurricane Irene brought to New England the black-spotted fruitfly, never seen here before and sighted in five states immediately after the storm. The females of this species have a saw-tooth ovipositor that can easily penetrate soft-skinned fruit such as blueberries, peaches and raspberries while they’re still growing. No need for fruit to ripen or start rotting first. A big problem.

• If you have grubs in a lawn, you should stop irrigating. Why? Because flying beetles go to moist places first. Who knew?

• In seven years, one deer couple can have 35 offspring. Deer overpopulation is a major cause of non-native plant invasion. The only cost-effective solution is to have hunters remove a doe first, before being allowed to take a buck. (This is going to go over great with the rack-hunters.)

• The Trustees of Reservations, the second-largest private land conservation organization in Massachusetts, faces an ongoing struggle with invasive plants. One big problem species? Hardy kiwi (Actinidia arguta), a plant only recently escaped into the wild. More on this just ahead.

Hardy kiwi: newly popular, wildly aggressive

One of the event’s two keynote speakers was Michael Clough, a specialist in Japanese knotweed. This plant has been causing trouble in the UK for decades and at this point the invasion is so widespread and scary that some banks refuse to grant a mortgage on property that contains even one sprig of the stuff.

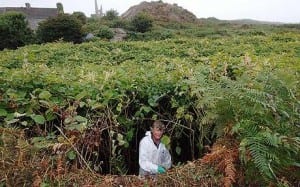

The story of knotweed’s origins in the UK is sadly identical to many invasion stories: it was enthusiastically marketed based on one or two appealing qualities (in this case those qualities were dune-stabilization and pretty flowers), then was introduced in ecosystems that lacked inherent biological controls, and now, more than a hundred years later, it has become disastrously rampant. Getting rid of knotweed requires either long-term herbicide application, or if that’s not possible in sensitive areas or where other valuable plants are growing, UK law requires digging nine feet down and 20 feet out in all directions, then sifting out the roots, and drying and burning them, or burying the excavated material 15 feet deep. What a frustrating, energy-sucking, royal pain.

How ironic, then, that the ELA event’s other keynote speaker was Ben Falk, of Whole Systems Design. Now, I confess that I couldn’t stay for Ben’s dinnertime address, so my comments are based on chats with others who did hear him, his website, and what I know of those who follow similar practices. Ben is one of a growing group of landscape professionals who advocate a renaissance of old-fashioned homesteading and 1970’s back-to-the-land values. They have revised and extended original permaculture ideas, creating their own modern set of solutions, relabeled with names like edible forest gardening, regenerative design, conscious system design or other inspiring terms.

This group of hard-working, hands-on garden folk perceive that the earth is in trouble, and they want to make things better: a worthy goal. Their approach is admirably multi-layered but focuses mainly on maximizing productivity of land and reducing the need for outside inputs. More worthy goals.

According to this school of thought, the highest and best use for land is to produce food and fuel for people. And there’s the problem. Like all the worst systems of agriculture and horticulture in our past, this new approach still places human wishes and desires (often called “needs”) in the center of the equation.

Which brings us back to hardy kiwi. This plant is widely used in edible landscaping plans, because it produces large, good-tasting fruit. It also grows fast and can thrive in a wide range of conditions, two qualities of invasive plants everywhere. And as we learned earlier, hardy kiwi has already become, in a very short time, a serious problem. It did not blow in on a storm or get carried here in the gut of a passing bird, which would be unfortunate but unavoidable. Hardy kiwi was introduced to our forests by well-meaning idealists, many of whom (coincidentally?) also adhere to the point of view that invasive plants are being unfairly maligned these days, and are really not so bad.

This is not Borneo. Still think hardy kiwi is no problem? We should know better by now. (Photo credit: Julie Richburg, TTOR)

These gardeners also promote using several other invasive plants, including autumn olive (a good nitrogen-fixer that helps other fruit trees grow!) and oriental bittersweet (when it kills trees, this opens up more space for growing food!). What about native plants and insects? What about harm to native ecosystems? Well, these things matter, but not as much as food and other things that people need.

So, progress or not?

My first thought, in light of the environmental damage resulting from this new school of thought, was to question ELA’s wisdom in choosing this particular closing speaker. From another perspective, though, it seems that ELA is carrying out its 20-year-long educational mission in the ideal way: by presenting several sides of an issue and leaving it to us to figure out what makes the most sense.

Both the Rhode Island Flower Show and the Garden Wise Symposium revealed great positive changes in our gardening values. The ELA conference, in contrast, presented complexity, reminding us that we must pay attention to the full meaning of our choices. New food-growing methods may aim to help the planet. But if they still place human interests before the health of the environment, and if they create new problems while trying to solve old ones, they may not be quite as beneficial in the long run as their enthusiastic practitioners proclaim. We need only look at two examples from the ELA conference – forests of knotweed in the UK, and natural areas in the US fatally carpeted in hardy kiwi – to remember that humans are no good at predicting anything about the natural world.