by Rebecca Lindenmeyr

The realization that nature can heal us is hardly new, but recent research has shown just how much we benefit from its close proximity. A 2016 review of 52 scientific articles on the ancient practice of Japanese “Forest Bathing”1 presents data to support that we have a positive physiological reaction when we are surrounded by nature. Specifically, our heart rate goes down about 5%, our blood pressure decreases, and we produce 15% less stress hormones. This autonomic nervous system reaction results in our being 56% more relaxed, which leads to improved cognitive function and enhanced creativity when we are in contact with nature.

Forward thinking businesses such as Amazon, YouTube, Google, Facebook, Airbnb, Lonely Planet, Kickstarter, Bank of America and TD Bank have taken note. They realized that if they want their workers to be less stressed and more focused and productive (and on average 20% more profitable), they can’t rely on the assumption that their workers will get up, get out, and seek nature. Instead they are bringing nature to people inside, up close and personal. It’s called Biophilic Design, and you’re going to start seeing it everywhere.

Nature Makes Us Better Humans

Nature Makes Us Better Humans

The term biophilia, stemming from the Greek roots meaning love of life, was coined in 1973 by the social psychologist Erich Fromm. It came into use in the 1980s when Edward O. Wilson, an American biologist, proposed that our evolution, occurring over 6-7 million years spent in nature, has soft-wired us to prefer natural settings over the built environment, and that we need to bring humans back in contact with nature for our sustained health and wellness. Neuroscientists studying “Attention Restoration Theory”2 found that views of complex, dynamic natural scenes such as waves, leaves in a breeze, fish swimming in an aquarium, or a flickering fire, capture and hold our attention better than artificial environments or stimuli.

Conversely, when we are immersed in artificial environments for extended periods of time our health declines. In chaotic and unsettling environments, the body’s sympathetic system is highly engaged in a “fight-or-flight” mindset. The parasympathetic system is suppressed, disrupting our natural balance and resulting in energy drain and mental fatigue. This combination induces stress, frustration, irritability, and distraction. Prolonged exposure to artificial environments (such as the traditional office building, school, or hospital) leads to a suppression of our immunity and delayed healing.

The positive effect of nature on humans is well documented– and yet despite overwhelming evidence we still don’t go outside, even though we know it’s good for us. According to the WELL Living Lab (a collaboration between the Mayo Clinic and Delos), on average we now spend 90% of our time inside (21.6 hrs/day), and only 10% of our time outside (2.4 hrs/day), and most indoor environments are making us stressed and physically ill. So why choose to stay indoors? The reality is that the majority of us prefer comfortable environments, (read lazy), and are easily distracted – I’m no exception. Even as a nature enthusiast with easy access to beautiful trails, I often look out my office window and say, “It’s a nice day; I should take a walk.” Then in the next breath I say, “Just let me answer this one email,” and I never leave my desk. Sound familiar?

Biophilic design bridges indoor and outdoor environments with shapes, forms, and materials originating in the natural world.

Bringing Nature Inside = Biophilic Design

In 1993 E.O. Wilson co-edited a book called The Biophilia Hypothesis with Dr. Stephen R. Kellert, a Professor Emeritus of Social Ecology at the Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Kellert is now one of the leading proponents of Biophilic Design in the U.S. His work focuses on understanding the connection between nature and humanity with a particular interest in environmental conservation and sustainable design and development.

“People possess an inherent need to affiliate with nature, something we have called biophilia. This can occur directly in the built environment through the experience of plants and natural lighting, but also indirectly through shapes, forms, and materials that originate in the natural world. Incorporating these features into the work place, through the application of biophilic design, can enhance employee health, motivation, problem solving, and creativity. In effect, it can lead to superior performance and productivity.”

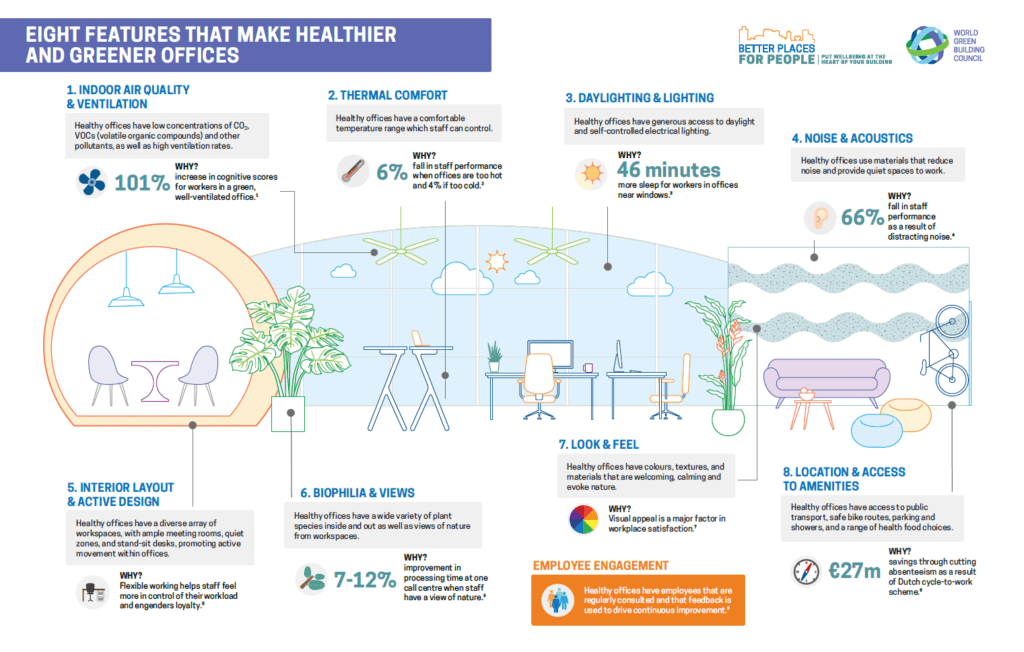

Benefits of Biophilic Design in our Built Environment

We can now prove that it makes financial sense to invest in biophilic design. Productivity, health, and well-being can be measured – metrics range from reduced absenteeism to greater worker satisfaction –and translated into dollar savings. In 2008, Kellert wrote a book with Judith Heerwagen, Martin Mador, along with Terrapin’s Bill Browning and Bob Fox, called Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Heerwagen, an expert in environmental psychology with the Office of Federal High Performance Buildings (USGSA), described how early pioneers in biophilic design are beginning to demonstrate tangible financial benefits.

In 2012, Bill Browning and his co-authors from Terrapin Bright Green published a report called “The Economics of Biophilia,” in which they showed that integrating views to nature in an office space can save over $2,000 per employee per year in office costs, whereas over $93 million in healthcare costs could be saved annually as a result of providing patients with views to nature. The 2015 the Human Spaces’ report, The Global Impact of Biophilic Design in the Workplace, found employees in environments with natural elements are reporting a 15% higher level of well-being, are 6% more productive, and are 15% more creative overall.3 Research also shows hospitals can shorten patients’ healing times by providing them a view of trees or other elements of nature from their beds. Schools that are incorporating Biophilic Design are reporting higher test scores by providing views of nature giving children greater access to the outdoors and encouraging contact with natural materials.

In 2012, Bill Browning and his co-authors from Terrapin Bright Green published a report called “The Economics of Biophilia,” in which they showed that integrating views to nature in an office space can save over $2,000 per employee per year in office costs, whereas over $93 million in healthcare costs could be saved annually as a result of providing patients with views to nature. The 2015 the Human Spaces’ report, The Global Impact of Biophilic Design in the Workplace, found employees in environments with natural elements are reporting a 15% higher level of well-being, are 6% more productive, and are 15% more creative overall.3 Research also shows hospitals can shorten patients’ healing times by providing them a view of trees or other elements of nature from their beds. Schools that are incorporating Biophilic Design are reporting higher test scores by providing views of nature giving children greater access to the outdoors and encouraging contact with natural materials.

How to Bring Nature Inside

In 2014, Terrapin Bright Green published a subsequent report titled “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design” which serves as a model for architects and designers looking to incorporate Biophilic strategies into their spaces. Here are the 14 Patterns:

Nature in the Space encompasses seven biophilic design patterns:

- Visual Connection with Nature

- Non-Visual Connection with Nature

- Non-Rhythmic Sensory Stimuli

- Thermal & Airflow Variability

- Presence of Water

- Dynamic & Diffuse Light

- Connection with Natural Systems

Natural Analogues addresses organic, non-living and indirect evocations of nature and encompasses three patterns of biophilic design:

- Biomorphic Forms & Patterns.

- Material Connection with Nature.

- Complexity & Order

Nature of the Space addresses spatial configurations in nature and encompasses four biophilic design patterns:

- Prospect

- Refuge

- Mystery

- Risk/Peril

Applying the Patterns and Principles

So how can we all reap the benefits of Biophilic design? Much of the research has focused on the workplace since it has the most direct and obvious economic impacts, but since we spend more time at home than at work I believe our residential built environment has as much of an impact on our health and well being as our workplace, and deserves as much attention.

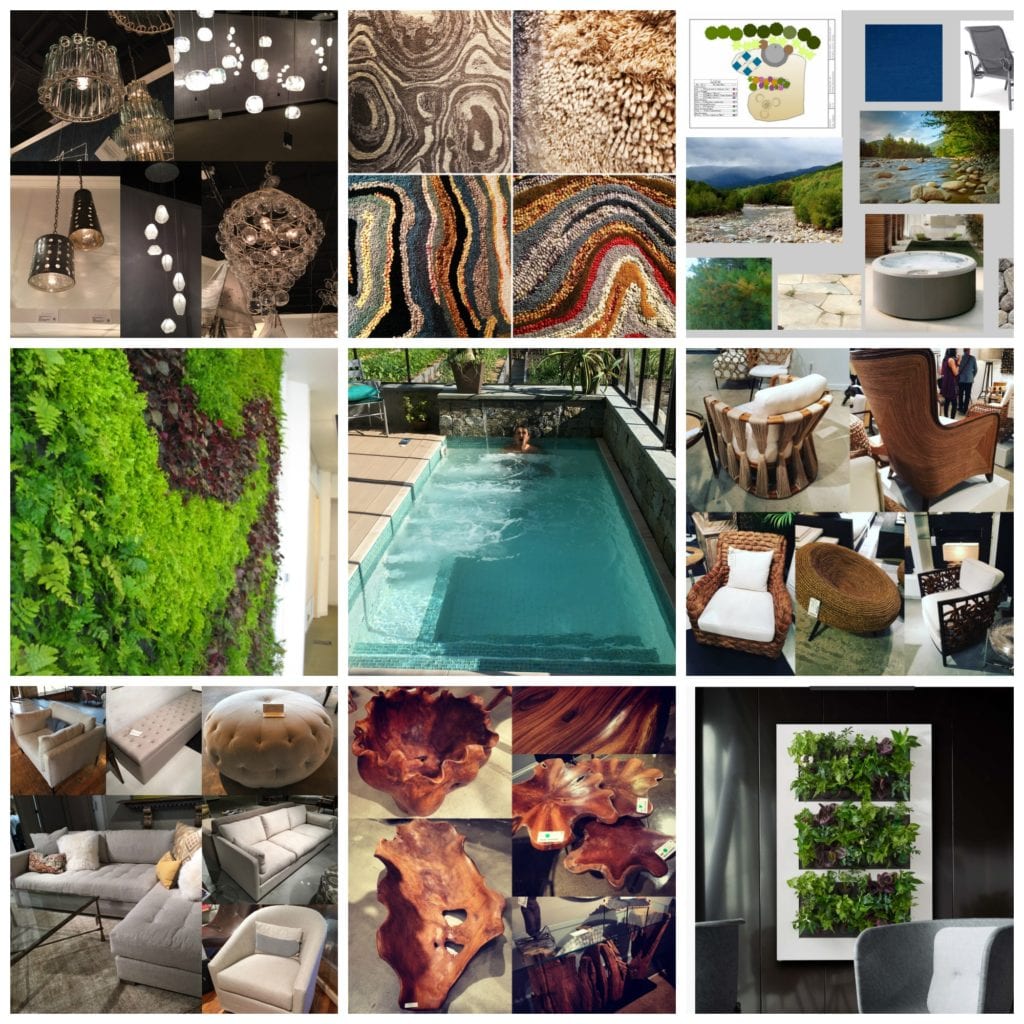

In our sustainable landscape and interior design practice at Linden L.A.N.D. Group in Vermont, we are applying the principles of Biophilic Design to connected indoor and outdoor spaces, in both residential and commercial settings. Specifically we work with architects, builders and homeowners to design spaces that include:

- Large windows that overlook complex but ordered landscapes, particularly multi-layered native woodlands, meadows, and ponds that attract wildlife including birds and pollinators

- Interesting kinetic sculptures and plants that move in the wind and change with the seasons

- Plant-filled atriums and conservatories that sustain greenery during our long winters

- Interior water features such as reflecting pools for fish, waterfalls, and solar-heated swim spas

- Colorful, living green walls that remove VOCs and other pollutants from the air

- Highly textured and touchable natural building materials such as wood, stone, and natural fibers

- Nature-based patterns in interior furnishings, (especially affordable, stylish, non-toxic and sustainable furnishings and textiles)

- Places for relaxing (refuge and prospect) such as cozy reading nooks and sunbathed window seats

- Places that are exciting and encourage movement (mystery and risk) such as overlooks, open stairwells, and meandering passageways inside that connect to paths outside and continue a journey

In essence, Biophilic Design creates fascinating, sustainable buildings connected to nature both inside and outside, which carry the promise of increased health and wellness, as well as increased productivity and reduced human resource costs. What’s not to love?

Learn More

Visit the following websites for more information:

Terrapin Bright Green – https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/report/14-patterns/

Human Spaces – http://humanspaces.com/.

Healthy Building Network – http://www.healthybuilding.net/

World Green Building Council – http://www.worldgbc.org/

References

1. Chorong Song, Physiological Effects of Nature Therapy: A Review of the Research in Japan, (Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016 Aug; 13(8))

2. Marc G. Bergman, The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with Nature, (Psychological Science December 2008 vol. 19 no. 12 1207-1212)

3. Sir Cary Cooper, Human Spaces: The Global Impact of Biophilic Design in the Workplace, (June 2015)

About the Author

Rebecca Lindenmeyr is a WELL AP and VT Certified Horticulturist, practicing Sustainable Landscape and Interior Design at Linden L.A.N.D. Group with her husband Tim Lindenmeyr in Shelburne, VT.