by Dan Jaffe

While there are about as many definitions of “invasive species” out there as there are definitions for “native species,” they all agree on a few basic principles: An invasive species is a non-indigenous species, introduced outside of its natural range (either intentionally or unintentionally), that causes ecological and/or economic harm. And there are a variety of invasive species in New England that fit this definition perfectly. Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), Norway maple (Acer platanoides), and burning bush (Euonymus alatus) check all the boxes when it comes to invasive species. Each one was brought in from outside of the United States, and each one has been amply documented as causing ecological and economic harm.

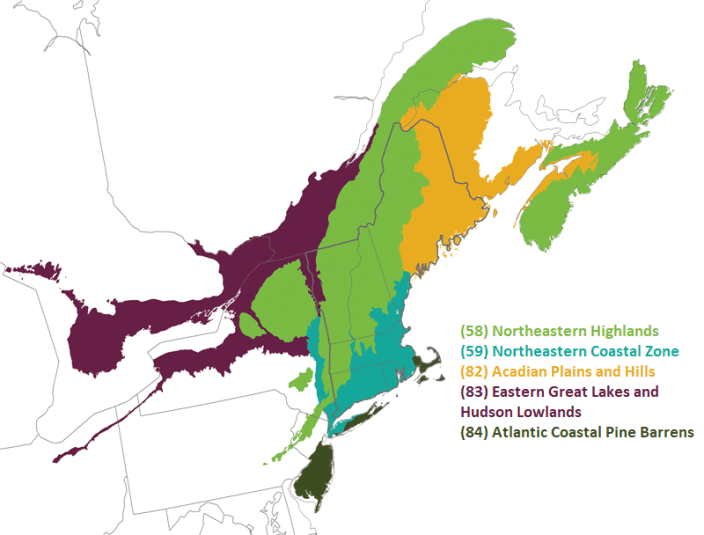

The ecoregions of New England. Many ecologists are looking at ecoregions as an improved method for defining native ranges as opposed to political lines.

Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) is considered invasive in Connecticut, Maine and Massachusetts, and yet it is native in Pennsylvania and could be considered native to the New England Ecoregions. (It is present in the Northeastern Highlands ecoregion). So the question arises, how do New Englanders deal with black locust?

Before examining black locust directly, we should first consider the patterns of successive effects that well-document invasive species display. Purple loosestrife invasions have been well documented, and though every situation has unique characteristics the overall pattern remains the same. Without natural controls in place, loosestrife displaces native species eventually taking over large swaths of their wetland habitat. Being a non-native species, the local wildlife doesn’t recognize the plant as food. A few generalist insects may use it as a nectar source, but native specialists, reliant on particular plant species to complete their life cycles, are left wanting. Accompanying an increase in loosestrife is a decrease in native wetland species such as blue vervain (Verbena hastata) and the verbena bud moth (Endothenia hebesana), which relies on the plant as a food source. The same can be said about the Io moth (Automeris io), which feeds upon rose mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos); the cattail caterpillar (Simyra insularis), which enjoys the taste of cattails (Typha latifolia); and hundreds of other species of specialist insects, not to mention the various birds and other animals that feed upon those insects. There is no question that ecological harm is being done.

Compare the example above to the entrance of the American chestnut into New England. After the glaciers retreated and trees began returning to New England, the forests were dominated by maple, birch, oak, and ash. These four species dominated for many years before slower moving trees (mainly hickory and beech) arrived. Many years later the first chestnuts finally arrived. In a relatively short period of time, the New England forests transformed from forests without chestnut to forests dominated by chestnut, with one out of every four trees an American chestnut. If we had been around at the time, we likely would have called the chestnut migration an invasion and done everything in our power to stop it. No doubt the rosy maple moth (Dryocampa rubicunda) wasn’t too pleased about the chestnut migration, but with the depletion of rosy maple moth habitat came the increase in Chestnut Clearwing Borer (Synanthedon castaneae) habitat, another native specialist. There are no similar tradeoffs when purple loosestrife invades a wetland.

Giant Leopard Moth is one of many native insects that use black locust as a host plant. Photo by Priscilla Chambers

The ecological domination of American chestnut was not the result of ecological degradation but rather of ecological change. But how does one make the distinction? In the short term it can be difficult to tell change from degradation, but hindsight is always 20/20. What can the chestnut’s story tell us about black locust? We can consider the beneficiaries, if any, of its presence in an ecosystem. According to Doug Tallamy (Author of Bringing Nature Home and coauthor of The Living Landscape) black locust is host to 67 native Lepidoptera, The London Natural History Museum counts 46 species and The National Wildlife Foundation lists 57. Black locust hosts species such as the locust underwing (Euparthenos nubilis), the giant leopard moth (Hypercompe scribonia), and the elm sphinx (Ceratomia amyntor). This means black locust hosts more species than eastern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), and sassafras (Sassafras albidum), three species native in New England. Of course, there is more than native insect ecology to consider when deciding whether a plant is beneficial or harmful to the environment, but we can draw a distinct difference between the effects of black locust on an ecosystem as compared to an invasive species from another continent.

There is no question that when black locust shows up in a new territory it leads to environmental change. This change is most evident in coastal communities where black locust’s ability to fix nitrogen can cause large scale environmental modification. Coastal communities are often dominated by plants adapted to low-nutrient soils, and black locust’s ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen significantly increases the available nitrogen. As the conditions change so do the inhabitants and many of the original plants are outcompeted and disappear from the landscape. Could these changes eventually lead to an entirely new and healthy environment or would the introduction of black locust simply destroy the current habitat? This question is difficult to answer now. We’d only be able to find a definitive answer by waiting and observing for 50, 100, or 1000 years, not a very practical approach to a current issue.

There are no simple answers here. Nature is never easy to label, and change occurs on a temporal scale that makes them hard for us humans to quantify. What we can determine is that black locust is distinctly different from most invasive species. This ambiguity is not an excuse to start planting black locust in New England (something that has already occurred and has likely aided its movement north), but instead poses new questions as to the nature of invasions and the unique characteristics of each species. Given the huge challenges involved in a successful invasive removal project, perhaps we should consider ecosystem-wide effects when deciding which invasions to prioritize.

About the Author

Dan Jaffe has over ten years’ experience with ecological horticulture. He is a propagator of native species, the photographer and author of Native Plants for New England Gardens and a lecturer on numerous topics including pollinators, sustainable landscape practices, foraging and cultivation of edible species, low-maintenance horticulture and others. He has developed a native plant horticultural database and has years of nursery management experience. He earned a degree in botany from the University of Maine, Orono, and an advanced certificate in Native Plant Horticulture and Design from New England Wild Flower Society. He is the Horticulturalist and Propagator for Norcross Wildlife Sanctuary in Wales, MA.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.