By Bella Ciabattoni and Pawel Pieluszynski

Mantids – The Voracious Generalist Garden Predator

While many insects often go unnoticed, one group never fails to attract attention. Large, charismatic, and bold, praying mantids are ferocious micropredators that delight anyone who stumbles across them. They have been touted as a gardener’s best friend, willing to dispatch any troublesome pest with their unrelenting appetite for other insects. However, there are more facets to this long-standing belief.

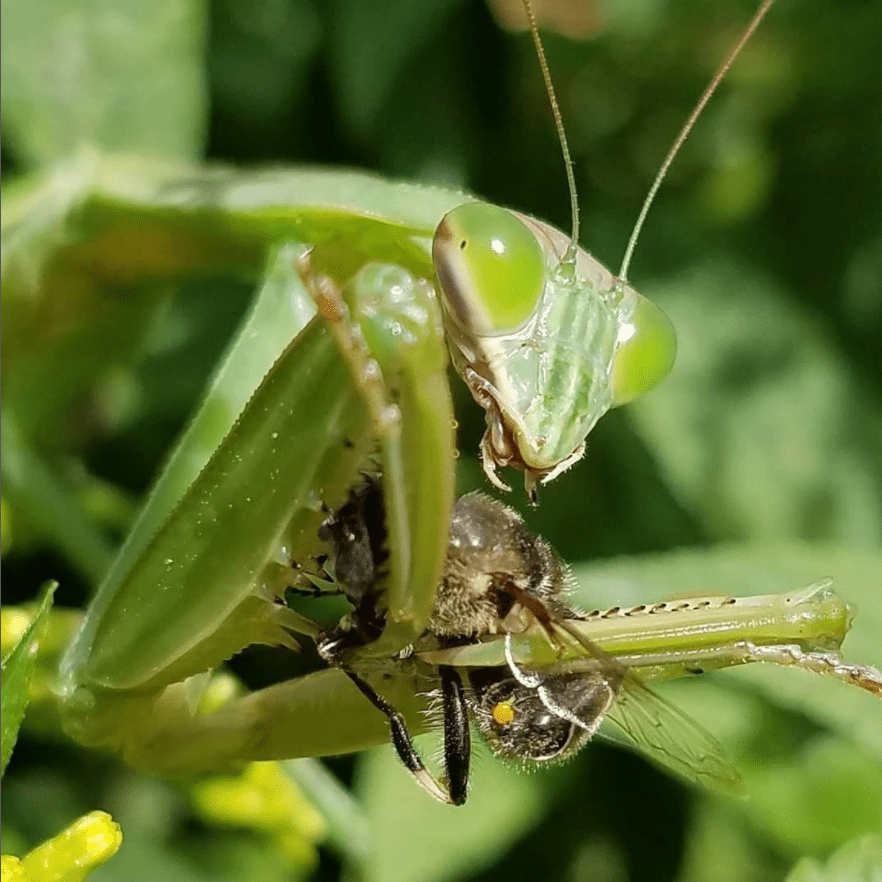

The truth is, the insects that mantids devour in our gardens are not exclusively horticultural pests but also other beneficial insects and species with declining populations, including those we are trying desperately to conserve. It can be argued that an over-abundance of mantids actually encourages the presence of some notorious horticultural pests, such as aphids, by eating large amounts of their highly-specific predators – the flower flies, also known as syrphid flies.

Figure 1: Tenodera sinensis eats a flower fly, a beneficial insect for pest control and pollination. Brooklyn Bridge Park. Pawel Pieluszynski. 2019

Most of the mantids people encounter in the northeastern United States are exotic species introduced by humans. The European mantis (Mantis religiosa), narrow-winged mantis (Tenodera angustipennis), and Chinese mantis (Tenodera sinensis) make up the bulk of the sightings. A fourth species, the Asian jumping mantis (Statilia maculata), is a relatively new introduction, gaining a rapid foothold in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area and New York City. Only one species is native to the northeastern United States: the Carolina mantis (Stagmomantis carolina). This species is near its northernmost boundary in New York City, and as our climate warms and changes, it is from here that it begins to make its way to more northern territories. Smaller than most non-native species, S. carolina can be outcompeted by the larger, invasive mantids and sometimes outright eaten by them. As a result, our native mantis is a relatively uncommon sight in our region.

Mitigating Predation Pressure in a Built Habitat

Brooklyn Bridge Park in Brooklyn, NY, is an entirely human-built 85-acre public waterfront park. We manage our garden beds as wildlife habitat: planting primarily native plants, using only organic techniques, and encouraging biodiversity through research and experimentation. In 2018, the horticulture team observed how mantids, especially the larger species, were indiscriminate predators that consumed large amounts of beneficial insects such as bumblebees, flower flies, butterflies, and other pollinators. While this behavior is the natural order in a biodiverse garden, an overabundance of large, generalist predators does not contribute to a healthy ecological balance.

A sure-fire way to find mantids within the park is to look upon patches of flowering plants in summer or fall, where there can be dozens of them waiting patiently amongst the blooms for visiting insects. It’s the mantis equivalent to an all-you-can-eat buffet! Often, there will be a pile of discarded monarch butterfly wings on the ground below these flowering plants, an alarming discovery for a gardener. Each time we’ve observed a monarch, bumblebee, or other large pollinator being consumed by a mantis, it has always been one of the two largest species – Tenodera angustipennis or Tenodera sinensis. It’s clear that the larger the mantis, the larger the prey they will eat.

Naturally, the more mantids there are, the more prey they consume. We took these frequent observations as signs that predation pressure from a large population of invasive mantids was becoming a threat to many of the insects we are attracting to the park – some of these insects have rapidly decreasing habitat in the wild. As gardeners and stewards of the land, we wanted to help mitigate this pressure.

Figure 2: A monarch butterfly captured and eaten by a mantis (Tenodera sp.) after landing to nectar on asters in the Flower Field. Brooklyn Bridge Park. Rebecca McMackin. 2019

Reducing Invasive Mantid Populations via Spring Cutback

In our plant beds, we often come across mantid egg cases or oothecae, each of which can contain up to 300 eggs. After reading about similar work done at Mt. Cuba Center, we decided to selectively remove and destroy mantid oothecae from certain high-pollinator traffic areas of the park. January through April is the best time to employ this type of mantid control. At this time of year in our region, all mantids from the previous season have died off, leaving only their oothecae behind to restart their populations once the temperatures are optimal. Our annual spring cutback, occurring in March & April, became the backdrop for this project.

One of the hotspots for pollinator and mantid activity at Brooklyn Bridge Park is the Flower Field, located on Pier 6 Outboard. The Flower Field is a half-acre, full-sun meadow filled with pollinator-favored native herbaceous perennials and many insect host plants. We’ve incorporated an ootheca collection project into our annual March cutback of the Flower Field each year since 2019. Since our cutback is entirely done by hand, it gives us the perfect opportunity to search for oothecae meticulously. We can remove them and record valuable information, all through performing our normal annual cutback.

Figure 3: The Flower Field in winter, pre-cutback. Brooklyn Bridge Park. Bella Ciabattoni. 2022

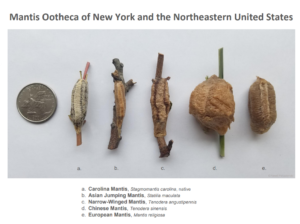

Identifying, Collecting, and Disposing of Oothecae

To protect populations of S.carolina during this project, it’s critical to accurately ID their oothecae. The first step to IDing them is to second guess it! The oothecae of T. angustipennis and S. maculata are commonly mistaken for S.carolina. Tenodera angustipennis is best distinguished by two dark parallel lines along the midrib. A grey color and a white midrib (the egg chamber openings) are good ID characteristics of S. carolina, more than size or shape. In contrast, the four non-native species have tan or beige-colored oothecae.

The best way to learn the difference is through visual comparisons. See the guide we’ve made below.

Figure 4: Mantis Ootheca of New York and the Northeastern United States, a visual guide. Pawel Pieluszynski

Flower Field cutback is a group endeavor, and all gardeners are instructed to quickly scan stems as they cut them back for oothecae of any species. When found, a piece of stem surrounding the ootheca is snipped off with it and collected. After cutback is complete, each ootheca is recorded. Data for each include species, the location where collected, and the plant species or structure was found. Afterward, S. carolina oothecae are placed back in the general area where they were found. Each ootheca of the other four species is disposed of by cutting them with pruning shears and then disposing them in a tied garbage bag.

Removing Oothecae Has an Immediate Effect

Repeating the collection three years in a row demonstrated that this method for reducing the presence of invasive mantids in a landscape is effective. In 2019, 154 oothecae were collected in the Flower Field during cutback. In 2020, only 21, and in 2021, only 32 were collected! The overwhelming majority of oothecae found have been of T. sinensis and T. angustipennis. Only a single S. carolina ootheca has been found in the Flower Field over the scope of the project.

One of the original objectives of this project was to see if reducing the populations of invasive mantids would bolster the numbers of S. carolina in that same space in the following years. Similar ootheca collection projects were carried out in two other meadows in the park, beginning in 2019. So far, our data does not consistently show this effect. In one meadow, S. carolina ootheca was found in 2020 when previously there were none, suggesting that this cause and effect may be possible. However, this was not the case in the Flower Field. In fact, the plant beds where S. carolina oothecae have consistently been found are on Pier 6 and are a far distance from the Flower Field. Many are found on woody perennials as opposed to herbaceous. This suggests more factors to consider in where S. carolina will roost and why. Perhaps their preferences for shelter and prey play a role.

The populations of invasive mantids in the Flower Field have not totally disappeared. That was never the goal and would be impossible to achieve if it were. Tenodera spp. is highly capable of flight, so even when all the oothecae in the meadow are removed, more from the adjacent plant beds and surrounding park will make their way in again. This is likely why there is still a consistent, though drastically reduced, presence of Tenodera spp. in the Flower Field after three years of this project.

There is still much to learn about how mantids behave in Brooklyn Bridge Park. As gardeners, we can fold these discoveries into our daily work and reoccurring tasks, like cutback. With consistency and time, it’s possible to uncover fascinating details about the spaces we work in.

Other Interesting Findings – Favored Roosts of Tenodera spp.

Through collecting data for this project, we saw several interesting patterns in the habits of these mantid species. Tenodera sinensis and T. angustipennis prefer roosting in Symphyotrichum oblongifolium ‘Raydon’s Favorite’ in the Flower Field, with 21% of total oothecae found on this plant in 2019, 67% in 2020, and 41% in 2021. This may be partly due to the high pollinator traffic this plant receives when in bloom and the feeding opportunities that it provides. Secondly, T. angustipennis tends to lay their oothecae on hardscaping such as light and fence posts more than other species. These are good hints on where to look for them in your own landscape.

Plant pest issues have not significantly increased in the Flower Field since beginning this project. On the contrary, the presence of at least one pest, the lace bug, has been decreasing every year since 2019 on patches of Symphyotrichum oblongifolium ‘Raydon’s Favorite’. Patches of this plant, as previously mentioned, are one of the mantids’ most favored roosts.

Figure 5: Three oothecae of Tenodera angustipennis laid on the same stem of Symphyotrichum oblongifolium ‘Raydon’s Favorite’ in the Flower Field. Brooklyn Bridge Park. Bella Ciabattoni. October 2019

Conclusion

For gardeners interested in “weeding” insects the same way we weed plants, we believe the strategy outlined above is an effective method of both reducing invasive mantid populations, encouraging our region’s only native mantis, and maintaining balance in a garden managed for biodiversity. Whether through a largescale seasonal project or casually throughout the year, removing invasive mantid oothecae could help your garden become an even safer haven for native pollinators and beneficial insects.

Learn more about the work we do at Brooklyn Bridge Park at Horticulture – Brooklyn Bridge Park

About the Authors

Bella Ciabattoni is Gardener II at Brooklyn Bridge Park. She manages the plantings on Pier 6 Outboard, a four-acre section of the park containing the Flower Field. In this native wildflower meadow, her adaptive spring cutback practices have shaped the space into effective wildlife and pollinator habitat. Before horticulture, she was an invasive species management technician and data manager for the National Park Service. You can contact her at gciabattoni@bbp.nyc or connect at Bella (@bella.novae.caesarea) • Instagram photos and videos.

Pawel Pieluszynski specializes in ecological horticulture at Brooklyn Bridge Park with a keen interest in entomology and native plant communities. He is currently pursuing a Master’s Degree in Biology at CUNY College of Staten Island. You can contact him at Ppieluszunski@bbp.nyc or connect at Paweł Pieluszyński (@metro_mushitori) • Instagram photos and videos

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.