By Nicole A Grant, Certified Yoga Therapist

Soaring Eagle.Photo by Chun Sun

Some of New England’s most esteemed minds found inspiration within the Old Manse walls of a Georgian clapboard house built in 1770 on Concord River banks. Ralph Waldo Emerson drafted his influential essay “Nature” here. He speaks with transcendental eloquence about the harmony between the natural world and human spirituality. In present-day Concord, MA, gardeners tap into this harmony by tending to perennial gardens and recreating the heirloom vegetable garden originally planted by Henry David Thoreau in 1842.

The Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts.

Emerson, Thoreau, and other philosophers recognized the Yogic Wisdom of a cosmic intelligence underlying this natural harmony. As a Yogini, I am fascinated with how closely attuned human physiology is to Nature’s rhythms and rituals. Many of us turn to Nature for solitude, solace, meditation, and regeneration. Yet, toiling with Nature as landscape artists do can have an adverse effect on our physical capabilities. We shape and charm the bud to “retell it in words and touch it is lovely, until it flowers again, from within, of self-blessing. ” How shall we apply the same deference and gentleness to our own inner landscape?

The Gardener and Nature

Consider one of my students, Sarah. She is an avid gardener and landscaper, and she advocates for postures to alleviate pain and stiffness in her back, knees, shoulders, fingers, and hands. Her back is tight from bending forward at the hips; her knees are compressed from squatting for extended periods; her upper back and shoulders are taut from craning her neck at awkward angles; and her fingers and hands are stiff with overuse and, possibly, arthritic joint pain.

I am an enthusiastic proponent of transplanting yoga from the mat into Nature to engage with Nature’s sounds and spectacles. In this age of COVID-19, there are the obvious benefits of fresh air and space. There is a powerful feeling when we embody Nature’s elements within an energetic practice of mindful movement, whether with yoga āsanas or with Qi Gong, a more accessible practice. There is a wisdom to these ancient practices, validated by neuroscience, that taps into the innate healing capacities of the mind-body-consciousness continuum.

Postural uprightness in our backs holds the integrity of our Central Nervous System. Any position that compromises the brain’s alignment with the spinal column, such that Sarah endures, ignites an over-efforting of our entire posterior chain (back-body) with ensuing strain, tension, and injury. From an energetic standpoint, these physical maladies can trigger our nervous system to high alert. This imbalance can evolve into a chronic, stressful state of being.

The Art of Lying Down

Lying down in Nature.

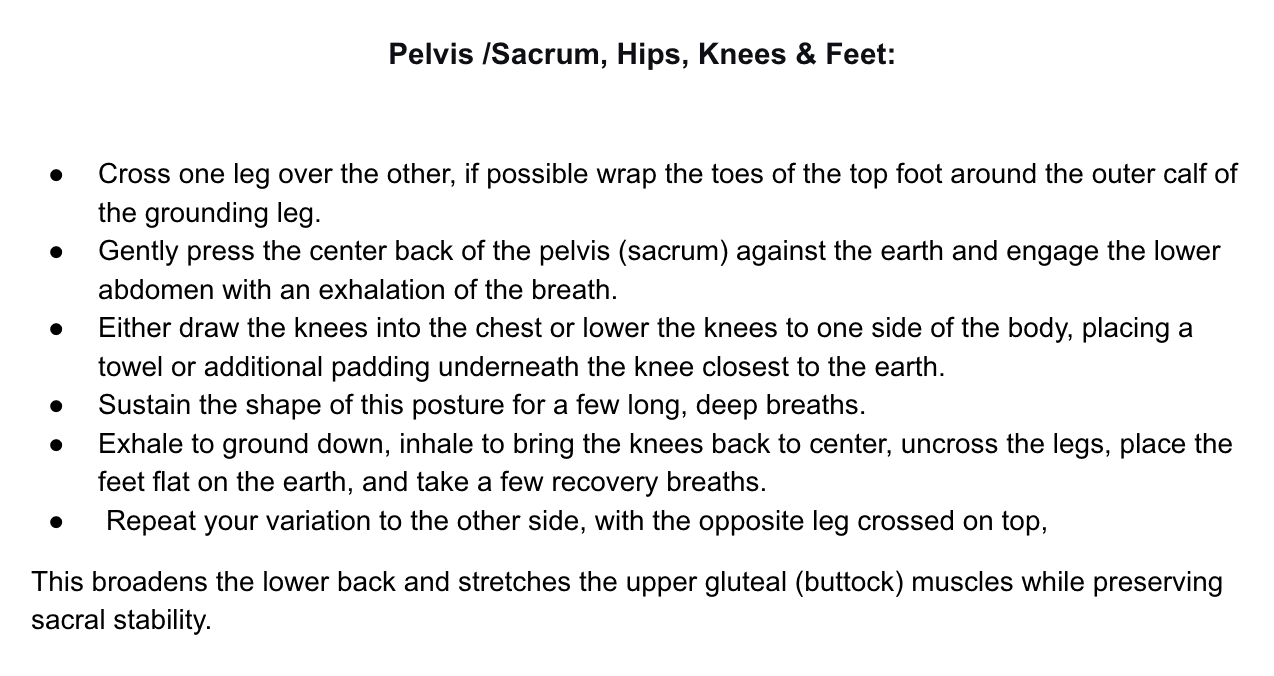

Lying down for short periods is one of the best things we can do to assist the recovery of all our body systems, yet one we rarely take time for unless to sleep. This supine position with the head (brain) and back braced by the earth, sacrum, and feet firmly grounded, heels under knees, anchors our entire being. On the one hand, we stabilize the nervous system, which invites the brain to perceive the body as “safe,” and the body then to relax and feel held. On the other, this supine position – where the head, mid-to-upper back, hips, and heels are all resting in the same horizontal plane, benefits our cardiorespiratory systems’ recovery. This heart and lungs position requires the least amount of effort to support respiration, circulation (vascular dilation), perfusion, and oxygenation of our cells and tissues. From this position, you can work with the hips, knees, and feet, alternating or simultaneously with the shoulder girdle, arms and hands, to varying effects.

Supta garudasana reclined Eagle pose.

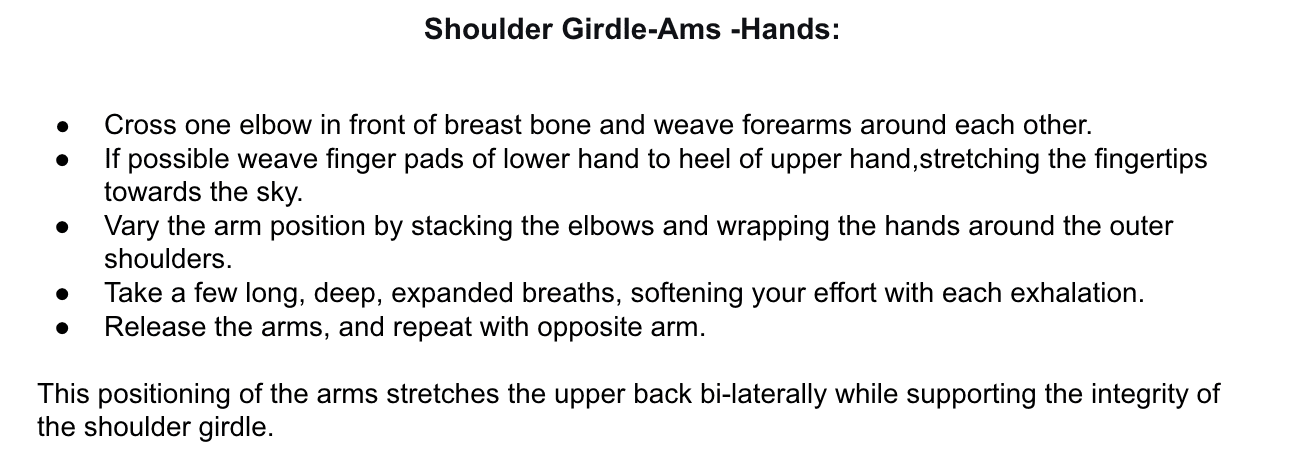

The reclined version of yoga’s eagle pose, or supta garudasana, broadens the back and stretches the muscles across the base of the neck, upper back, and shoulder blade. This region often overexerts when we pitch the head or torso forward of the body’s upright position, such as when one might lean over to pull a weed beyond easy reach. If the head tips back or feels strained in this reclined position, place a folded blanket under the head and neck (but not the shoulders).

The Sacrum

The Sacrum

The sacrum comprises five fused vertebrae at the inferior end of the spine. It forms the spinal column’s solid base, where it wedges into the ilium (posterior hip bone) to articulate with the pelvis (SI joints). The sacrum is a solid bone that supports the upper body’s weight as it is spread across the pelvis and into the legs. The shape of our “seat” can compromise the sacroiliac joints.

The first action (knees to chest) will apply traction to the lower back while protecting the sacrum; the latter brings traction to the lateral (outer) aspect of the top leg’s hip and gluteal muscles while massaging the abdominal organs with the rolling-twisting action of the belly. Whether you are an adept yogi or new to the practice, stay with the pose you are in long enough to breathe and notice the sensations that come up for you, in your body, in the moment.

The first action (knees to chest) will apply traction to the lower back while protecting the sacrum; the latter brings traction to the lateral (outer) aspect of the top leg’s hip and gluteal muscles while massaging the abdominal organs with the rolling-twisting action of the belly. Whether you are an adept yogi or new to the practice, stay with the pose you are in long enough to breathe and notice the sensations that come up for you, in your body, in the moment.

Photo by Chun Sun

The eagle is often a solar symbol and is associated with pretty much all known sky gods. This bird of prey embodies inspiration, release from bondage, victory, longevity, speed, pride, and royalty. Yoga’s upright ‘eagle pose,’ or garudasana, invokes the mythic bird and becomes a practice of strength, flexibility, and endurance. Standing, one learns to cultivate steadiness in the difficulty of balance, the listing from side to side, which teaches unwavering concentration, steady gaze, an eagle’s sight. This steadfastness of concentration calms the mind and expands our consciousness in all directions.

However you choose to engage your body consciously, approach every sensation that arises in your awareness with compassion and quality of curiosity, as you might a bud before it blooms. Sensation is the language of the body. Breath-by-breath, we learn to cultivate strength in the steadiness of action as we fine-tune our understanding of the sensations and feelings that show up in our body. We learn to respond to our inner and outer gardens without compromising our physical and mental integrity.

1 From Saint Francis and The Sow by Galway Kinnell, American Poet

Eagle Photo Credits Chun Sun Concord, MA

About the author

Nicole A. Grant, MS, C-IAYT, E-RYT500, EMT, Mother-of-2. Practitioner of yoga. Certified yoga therapist and trainer. Founder, Yoga Mandala studio (2001) and The Mandala Project (2020)Yoga Mandala Online Yoga Classes. Author/writer (Yogini’s Dilemma: To Be or Not To Be A Yoga Teacher, Morgan James, 2020). Educator, strategic design thinker, and purveyor of services (for Be Well Be Here) offering outside-the-box approaches to elevating social-emotional well-being for personal and professional resilience and sustainability. Neuroscience and epigenetics nerd. Mentor for youth in foster care (Silver Linings Mentoring). International American. World Traveler. Random conversationalist. Non-traditionalist. Lover of adventure, animals, and the great outdoors, green tea and dark chocolate. ‘Just licensed’ (EMT) to mitigate emergent health conditions out in the field and bring yoga off the mat!

Nicole A. Grant, MS, C-IAYT, E-RYT500, EMT, Mother-of-2. Practitioner of yoga. Certified yoga therapist and trainer. Founder, Yoga Mandala studio (2001) and The Mandala Project (2020)Yoga Mandala Online Yoga Classes. Author/writer (Yogini’s Dilemma: To Be or Not To Be A Yoga Teacher, Morgan James, 2020). Educator, strategic design thinker, and purveyor of services (for Be Well Be Here) offering outside-the-box approaches to elevating social-emotional well-being for personal and professional resilience and sustainability. Neuroscience and epigenetics nerd. Mentor for youth in foster care (Silver Linings Mentoring). International American. World Traveler. Random conversationalist. Non-traditionalist. Lover of adventure, animals, and the great outdoors, green tea and dark chocolate. ‘Just licensed’ (EMT) to mitigate emergent health conditions out in the field and bring yoga off the mat!

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.