Interview with Amanda Sloan

Introduction

Along the north shore of Lake Massapoag, a 350 acre natural lake in Sharon, Massachusetts, the public beach was in need of restoration. “A labor of love” is the way that long time Sharon resident and landscape designer, Amanda Sloan, describes the five year project. In a collaborative effort involving State and local funding, the project focused on incorporating concepts of ecological design and respect for the natural indigenous features.

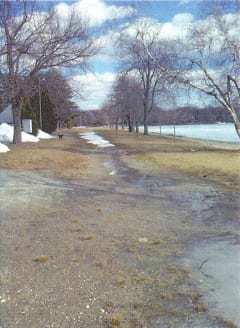

Memorial Park Beach’s old road bed, shown before restoration, experienced erosion (visible in foreground).

Background

Lake Massapoag is truly the “heart” of Sharon, a sleepy New England town 30 miles south of Boston. The lake has been central to town history beginning in pre-colonial times when Wampanoag and Massachusetts Indian communities thrived in this area and the lake was hunted and fished. In colonial times the lake was dredged for iron ore to make cannon balls for the Revolutionary War. Paul Revere owned the water rights to Massapoag for many years and used the power of Massapoag Brook, the lake’s outlet stream, to run his copper mill. In Victorian times the lake was home to many grand resort hotels for guests escaping Boston in the summer. As on many New England freshwater bodies, ice was cut on the lake in wintertime and transported to customers by a spur rail line. By the 1980’s, Lake Massapoag had become, as the town recreation director liked to say, “Sharon’s most valuable recreational asset.” With only a few shoreline homes, it still boasted forested shores and did not have the look of an urban lake. Swimming, boating, skating, and fishing were all enjoyed on the lake by residents.

Project Beginnings

As an environmentalist and landscape designer, Amanda Sloan noticed on many trips to the lake’s public beach with her children that there was something missing—something to do with the “genius loci” or “soul” of the place. Although the lake was itself quite healthy, people were losing touch with its ecological importance to the town. Sharon pumps its own water, and the lake is connected to the aquifers. Massapoag Brook is the headwaters of the Neponset River, an important regional waterway and habitat.

It concerned Amanda that Memorial Park Beach itself was becoming worn and shabby, with eroding shores, compromised trees, and no thought given to the ways this central landscape served as a touchstone in the community. In a conversation with the recreation director, Amanda learned that he was looking for an opportunity to improve Memorial Park Beach, but did not know where to start or exactly what was wrong with the place. Hence, a project was born!

The goal would be to create and implement a new landscape master plan for the park that sensitively combined ecological restoration and enhancement of the lakeshore, while evoking, through the park landscape, the lake’s historical and recreational qualities, and most importantly, expressing the deeply cherished quality of the landscape in the heart of the community.

The stripping of vegetation to clear the shore, plus dumping of sand to artificially provide an “ocean beach” recreational area at an inland freshwater lake, plus heavy foot traffic, all combined with the naturally strong wind conditions and resulted in yearly erosion and exposed roots. Lake water quality and even bottom depth were being affected by the eroding sand. Attempts had also been made for many years to plant a lawn down to the “beach.” This attracted geese, necessitated irrigation and fertilizer, and could not hold the bank.

Amanda has observed that in New England, this “beach sand and/or lawn” treatment is typical at lakeside properties both public and private, where caretakers have not been educated as to the importance of leaving buffer plantings, and users expect an “ocean beach” type environment with expanses of sand. Caretakers, municipal officials, and users need to be educated as to the special qualities of our New England kettlehole lakes and ponds. Although there were many challenges on this project, the need for an “attitude shift” by park users around the quantities of sand vs. plantings, and the necessity to allow some portions of shore to return to a “wild” state, was perhaps the biggest challenge and is one that is still ongoing.

To address site degradation, project goals included the reduction of lawn, restoration of buffer plantings consisting of native plants, judicious grading of heavily traveled paths away from the shore, placement of infiltration trenches and swales, use of curving, switchback, and biomorphic forms (i.e. no straight lines), use of native and recycled materials, and no irrigation.

DPW maintenance vehicles including landscape maintenance and trash removal routinely drove across the man-made beach. If left natural, this area would have been filled with low shoreline plants and small trees, providing the benefits of erosion control, water purification, and habitat. An aim of the project was to begin to restore this natural planting.

Construction

Construction

The project was divided into three phases beginning at the shoreline, where the damage was greatest and permits would be needed, and proceeded in steps backward toward the inland section. So, Phase 1 was shoreline restoration and planting; Phase 2 was reconstruction of the old roadbed into a multiuse path with infiltration trench, bench and kiosk installation, and plantings; and Phase 3 was inland slope restoration, accessible paths, gardens, steps, and bike racks.

To manage the project Amanda coordinated with David Clifton, the town Recreation Director, Peter O’Cain, the Town Engineer, and Kevin Weber, the town Trees and Parks Warden. In addition Amanda had excellent support and assistance from Greg Meister, the town’s Conservation Agent. The project was initially launched with a community design charrette at which invited park stakeholders did some “blue skying” about what the vision for the landscape would be. For each phase, town boards such as the Selectmen, Finance Committee, Conservation Commission, and Recreation Advisory Committee were met with and presented with schematic plans and estimated budgets. Each phase of the project had to go through the annual Town Meeting in order to be funded. When environmental permitting was required, Amanda worked closely with the Conservation Commission to file paperwork and obtain necessary State and local permissions (Phases 1 & 2 operated under “orders of conditions” both from the town and from the State).

During each phase, the winter would be spent on the computer creating the packages of construction documents that would go out to bid as a Town of Sharon job in early spring. Once the job had been awarded to a construction contractor, Amanda switched hats from “CAD jockey” to “construction manager” and was on site each day to observe construction. Because the park received its heaviest use in the summer after the July 4th holiday, the goal in each of the three phases was to have work completed by that date. Therefore it was essential in each phase to start the planning with a calendar, count back the months, and stick carefully to deadlines. Amanda notes that the intensive year-round schedule, and a few missed deadlines here and there, accounted for the fact that a three-phase project required 5 years to complete!

Phase 2 included the installation of an infiltration trench along the entire inland length of the new multi-use path. The path was of permeable packed stonedust and was cross-graded to drain inland into the trench. The trench was a buried tube of sharp gravel wrapped in permeable fabric and covered with loam and grass. The trench was engineered to hold and infiltrate stormwater into the shoreline rather than allow it to sheet drain and erode the shore. All soil excavated was reused on site.

Phase 2 included the installation of an infiltration trench along the entire inland length of the new multi-use path. The path was of permeable packed stonedust and was cross-graded to drain inland into the trench. The trench was a buried tube of sharp gravel wrapped in permeable fabric and covered with loam and grass. The trench was engineered to hold and infiltrate stormwater into the shoreline rather than allow it to sheet drain and erode the shore. All soil excavated was reused on site.

Gravel base materials and planting loam were brought to the site. For the planting medium, percentages of organic and other materials were detailed in the written specifications for the job. Because this was a large job that went out to public bid, formal Specifications were written for all materials and construction methods, and these were part of the official Construction Documents. Amanda points out that it is important on large jobs to edit boiler-plate specifications to include environmentally appropriate standards to make sure materials, seed mixes, procedures, etc. meet ecological goals.

Gravel base materials and planting loam were brought to the site. For the planting medium, percentages of organic and other materials were detailed in the written specifications for the job. Because this was a large job that went out to public bid, formal Specifications were written for all materials and construction methods, and these were part of the official Construction Documents. Amanda points out that it is important on large jobs to edit boiler-plate specifications to include environmentally appropriate standards to make sure materials, seed mixes, procedures, etc. meet ecological goals.

Additional stormwater management included the construction of the low boulder retaining “strands.” These were another way to stop sheet drainage to the lake, and stop and infiltrate stormwater. They also provided a protective soil cover, “safe” growing area for the damaged trees with exposed roots, and a place to start establishing a planted buffer for the shore. A side benefit is that they provide a wonderful seating area along much of the shore.

Additional stormwater management included the construction of the low boulder retaining “strands.” These were another way to stop sheet drainage to the lake, and stop and infiltrate stormwater. They also provided a protective soil cover, “safe” growing area for the damaged trees with exposed roots, and a place to start establishing a planted buffer for the shore. A side benefit is that they provide a wonderful seating area along much of the shore.

The serpentine “strands” were made of boulders quarried of local granite in nearby Rockland. Just behind the boulders, permeable landscape fabric was installed to contain fines from the planting medium so that it does not wash through the wall into the lake. Temporary erosion control fencing protected the lake during construction—-part of town and State requirements for construction near wetlands.

A vegetated buffer was started along the section of “beach” and a permeable stonedust multiuse path was created along the entire length of the park in order to promote walking and bicycling and to make the park accessible to wheelchairs. Along the path, islands of native plants were created in an area that had previously been bare sand.

Recycled materials removed from Sharon streets during previous road projects were used on the project for several sets of granite steps.

Recycled materials removed from Sharon streets during previous road projects were used on the project for several sets of granite steps.

The granite cobble used to pave small areas throughout the park was reused local cobble. In addition, the wood rails at the edges of the parking lots were recut and reused during configuration of new accessible ramps down to the multiuse path. The bench slats were all recycled plastic wood.

All plants on the plant lists for all three phases were either native or historically adapted to a New England lakeshore environment. Most are native, but there were two non-native “historic touchstone” plants. The first was the weeping willow, planted because they are not harmful or invasive and were historically seen at the park. The other non-native plant was rugosa rose—“Frau Dagmar Hastrup” that is pale pink and behaves itself beautifully!

All plants on the plant lists for all three phases were either native or historically adapted to a New England lakeshore environment. Most are native, but there were two non-native “historic touchstone” plants. The first was the weeping willow, planted because they are not harmful or invasive and were historically seen at the park. The other non-native plant was rugosa rose—“Frau Dagmar Hastrup” that is pale pink and behaves itself beautifully!

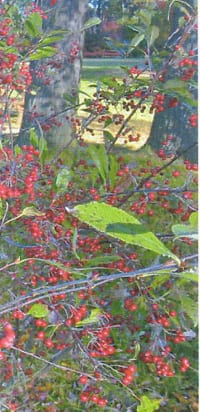

Other plant material included aronia arbutifolia (chokeberry), aster, comptonia (sweetfern), rhus aromatica (fragrant sumac), tupelo, oxydendrum, bearberry, sedges, rushes, native grasses such as panicum, pitch pine, juniper, blueberry, bayberry, clethra, rudbeckia, solidago, xanthorhiza simplicissima (yellowroot) … and many more.

Other plant material included aronia arbutifolia (chokeberry), aster, comptonia (sweetfern), rhus aromatica (fragrant sumac), tupelo, oxydendrum, bearberry, sedges, rushes, native grasses such as panicum, pitch pine, juniper, blueberry, bayberry, clethra, rudbeckia, solidago, xanthorhiza simplicissima (yellowroot) … and many more.

Luckily, there was not an invasive plant problem at the lakeshore. The new planting areas are actually sprouting more self-sown desirable natives than anything else.

The plantings were designed so that no irrigation would be needed except for a few weeks after planting to get established. To have a successful design without irrigation systems, plants had to be drought tolerant, wind tolerant, and trample tolerant. With careful planning, very few plants were lost after installation.

A small area of turf was preserved behind the retaining boulders for spreading towels after swimming. However, these areas were all resown with a native “Ecology Mix” grass seed that included mostly fescues. It has been fantastic, greens up and stays low, needs little mowing and no irrigation.

Along the shoreline are acer rubrum, native swamp maples, which are among the original park trees. With erosion problems addressed, they are recovering nicely. Their fall color is spectacular along the lakeside.

“The park is wild in character requiring little maintenance (spring and fall pruning and raking only) and visitors don’t mind it like that,” Amanda notes. “For a formal city park this might be an issue, but by the lake it works fine and is part of the attitude education mentioned earlier.”

“The park is wild in character requiring little maintenance (spring and fall pruning and raking only) and visitors don’t mind it like that,” Amanda notes. “For a formal city park this might be an issue, but by the lake it works fine and is part of the attitude education mentioned earlier.”

Garden color highlights include rudbeckia hirta “Herbstonne,” prairie coneflower. Though it gets very tall, it stands up to constant wind, is natural and beautiful looking and really makes a statement!

Along part of the slope, turf has been replaced with a meadow-type planting. It has grasses, blueberry, solidago, and lots of coneflower.

Along part of the slope, turf has been replaced with a meadow-type planting. It has grasses, blueberry, solidago, and lots of coneflower.

Alongside the meadow planting, are the “amphitheater steps.” Reused granite was installed to address a serious erosion problem and create a functional stairway that leads up to the bath house.

Native plants were used in many ways in the park restoration. Rhus aromatica, (fragrant sumac), a great low-growing native plant, holds a bank and survives any drought. In front of the sumac, a white woodland aster self-sowed—how lucky!

Native plants were used in many ways in the park restoration. Rhus aromatica, (fragrant sumac), a great low-growing native plant, holds a bank and survives any drought. In front of the sumac, a white woodland aster self-sowed—how lucky!

Unsightly drainage pipe and stormwater runoff was addressed with a native rock surround and a drainage area planting of sedges and rushes.

Unsightly drainage pipe and stormwater runoff was addressed with a native rock surround and a drainage area planting of sedges and rushes.

In another location, drainage was addresed with a slight swale that was introduced in the grade and reused cobble was installed to catch and infiltrate stormwater—like a Japanese stone drain. The cobble sits atop 18” of gravel for drainage.

In another location, drainage was addresed with a slight swale that was introduced in the grade and reused cobble was installed to catch and infiltrate stormwater—like a Japanese stone drain. The cobble sits atop 18” of gravel for drainage.

Amanda designed two information kiosks for the park, placed at each end of the multiuse path to encourage people to stroll along and see what’s posted. The design is similar to the lake flume house nearby. The kiosk near the boat launch includes information on fish species and fauna and flora found in the lake—on the other sides there are posters about the history of the lake and a map showing how the lake connects to other water bodies and natural areas. This information prompts visitors to better understand the lake and its ecological, social, and historic function.

Amanda designed two information kiosks for the park, placed at each end of the multiuse path to encourage people to stroll along and see what’s posted. The design is similar to the lake flume house nearby. The kiosk near the boat launch includes information on fish species and fauna and flora found in the lake—on the other sides there are posters about the history of the lake and a map showing how the lake connects to other water bodies and natural areas. This information prompts visitors to better understand the lake and its ecological, social, and historic function.

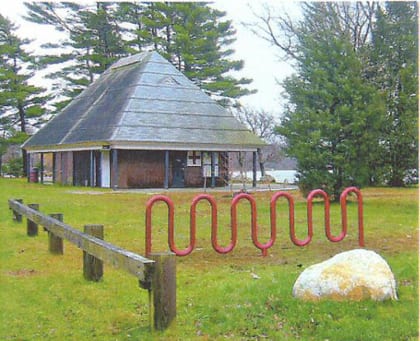

New bicycle racks in front of the original bath house now encourage visitors to bike rather than drive to the park.

New bicycle racks in front of the original bath house now encourage visitors to bike rather than drive to the park.

An elementary school environmental art project helped “reconnect” town children with the lake. The students learned about town history as it relates to the lake, starting with Native American times. They then painted tiles with scenes from the history they had learned. The tiles were mounted on cedar posts, in sequence, so they form a visual “walking timeline” of lake history. This is set along the multiuse path from end to end. This post depicts a bluebird and a fox. Benches were installed along the path – there were no benches to sit and enjoy the lake before this project. The benches use recycled plastic slats.

An elementary school environmental art project helped “reconnect” town children with the lake. The students learned about town history as it relates to the lake, starting with Native American times. They then painted tiles with scenes from the history they had learned. The tiles were mounted on cedar posts, in sequence, so they form a visual “walking timeline” of lake history. This is set along the multiuse path from end to end. This post depicts a bluebird and a fox. Benches were installed along the path – there were no benches to sit and enjoy the lake before this project. The benches use recycled plastic slats.

In 2006, the park was designated as a part of the Bay Circuit Trail, Boston’s “Outer Emerald Necklace” linking trails from the north shore to the south shore in a continuous circuit.

With the state grant, the project cost was about $250,000 – a bargain for a restoration of a 14-acre park. Amanda Sloan believes that the cost was kept low in part because of the ecological landscaping principals used. Plant use was maximized. High-cost hardscape was kept to a minimum, favoring native boulders, reused granite cobble, and curbing. Site engineering was also kept to a minimum maintaining the existing lay of the land, except where it needed correction to stop erosion.

With the state grant, the project cost was about $250,000 – a bargain for a restoration of a 14-acre park. Amanda Sloan believes that the cost was kept low in part because of the ecological landscaping principals used. Plant use was maximized. High-cost hardscape was kept to a minimum, favoring native boulders, reused granite cobble, and curbing. Site engineering was also kept to a minimum maintaining the existing lay of the land, except where it needed correction to stop erosion.

The completed restoration of Memorial Park Beach achieved the objectives of ecological restoration and lakeshore enhancement, while recognizing the lake’s historical perspective and reestablishing the park’s essential sense of place in the heart of the Sharon community.

The completed restoration of Memorial Park Beach achieved the objectives of ecological restoration and lakeshore enhancement, while recognizing the lake’s historical perspective and reestablishing the park’s essential sense of place in the heart of the Sharon community.

Community residents now enjoy Amanda’s “Labor of Love” – the five year restoration of Memorial Park Beach.

About the Author

Amanda Sloan is a landscape designer specializing in planting design, sustainable techniques, and residential landscapes with Gates, Leighton and Associates Landscape Architects (GLA) in East Providence, Rhode Island. An environmentalist, she is a board member of the Community Design Resource Center of Boston and the Sharon, Massachusetts Planning Board. Formerly with Julie Moir Messervy and Associates Landscape Design Consultants, Amanda has 15 years of experience in the practice of landscape design.

Amanda will be a featured speaker at the upcoming ELA Conference & Eco-Marketplace where she will present: At Home with Sustainable Landscapes Design. For more information about the Conference and additional details about Amanda’s presentation, visit: ELA Conference & Eco-Marketplace.