by David Seiter

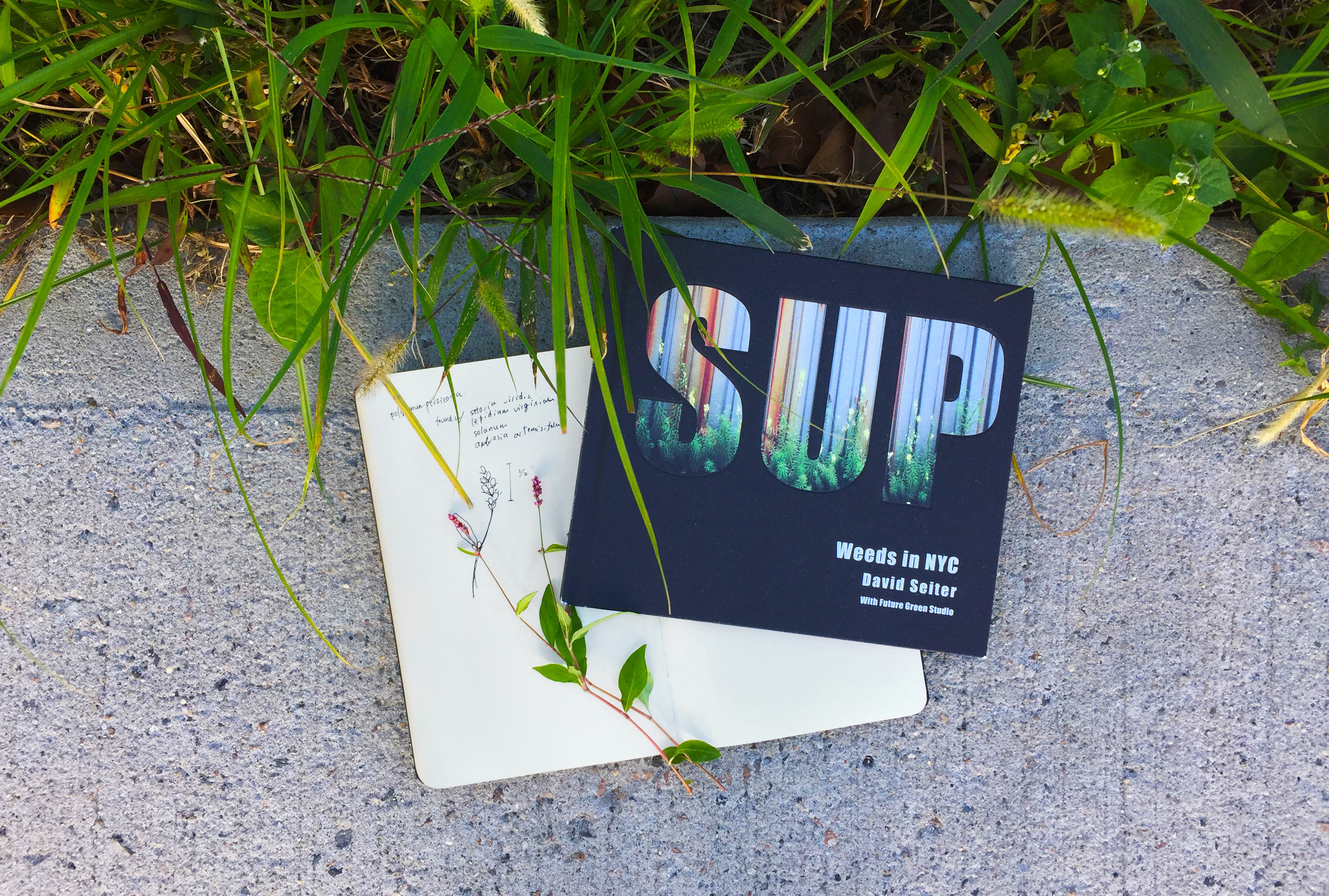

The following excerpt from Spontaneous Urban Plants: Weeds in NYC is reprinted with permission of the author.

Whenever travelling to a new city, I always want to understand its layout, its sequence of spaces, its edges and boundaries and the relations between urban landscapes and landmarks. While reading a map helps to provide one kind of perspective on the city, there is nothing like just getting lost and wandering as a way to orient yourself to your surroundings.

The rhythm of your steps and the open-ended nature of your route allows your mind to drift, helping you to slip into a meditative state that opens your acceptance of the unexpected and the overlooked. Streets, sidewalks and signs don’t direct your movement through urban space but rather your path is determined by your intuitive sensibility. Drawing on social, spatial and eidetic cues, the wanderer follows their instinctual motivations to inhabit space, reading the psychogeographical terrain of the city to reveal its poetic nature. This way of moving through the city breaks down the hegemony of planned urban sequences and suggests a deeper reading of the city that is from the ground up and emergent. In this spirit, wandering is understood as an investigative practice and a method towards a new way of seeing.

In today’s digitally navigable world where nearly everyone has a smartphone with mapping apps a touch away, it is more important than ever to walk off the beaten track and explore the remnant urban fragments that are not digitally mapped on navigational devices. Wandering the de-mapped zones of abandoned parks, waterfront dead-ends, infrastructural edges or vacant lots is an opportunity for urban dwellers to actively traverse and reconsider their surroundings as a shifting landscape that can be reshaped by their own perceptions. Architect and professor, Francesco Careri, in his book, Walkscapes writes “…walking is an aesthetic tool capable of describing and modifying those metropolitan spaces that often have a nature still demanding comprehension, to be filled with meanings rather than designed and filled with things.”[i] The underutilized spaces of our cities often contain a persistent wild nature that warrants attention and holds significance. These void spaces are essentially a landscape or a sort of connective tissue that exists only where the structure doesn’t. Walking through these “spaces in between” may help us to reveal the latent potentials that each plant or site holds – motivating us to fill our urban voids with meaning instead of things.

The City is the site – the focus of our wandering investigation. New York City functions somewhat like a vast ecosystem that is constituted by its diverse sets of people, its remnant, patchwork ecology and its aging infrastructure of roads, buildings and systems. In New York City, sometimes it’s easy to get caught up in the hustle-bustle and forget about the “nature” part of that equation. At the end of my first month of working in the city, I was walking down Varick Street just south of Houston and passed by construction workers that were tearing up the sidewalk. The rich, reddish-brown, fecund earth was spilling out of the hole and smeared onto the sidewalk. I reached down and grabbed a handful. I simply could not believe that the earth actually existed under the pavement. I hadn’t seen real dirt in so long that I truly forgot that it was subversively lurking under all that concrete. Nature still existed – I had just overlooked it. At the time, it made me think of art historical references like Marcel Duchamp’s “Readymades” or Robert Smithson’s “Theory of Non:Sites” where the found object is removed from its original location and through its repositioning, a deeper, more significant meaning is revealed.

When analyzing our urban ecology with a critical eye towards repositioning its mundane and found conditions, the most dominant, self-replicating natural system operating in our disturbed landscapes is the loose network of spontaneous vegetation. In the urban realm, these volunteers are often unwanted and every attempt is made to eradicate them. Instead of dismissing them, we should be trying to understand why spontaneous urban plants are so successful in our tough urban conditions. These conclusions might provide the biggest insight for designers to strategically rely on the ecological services of spontaneous urban plants in the face of climate change.

Climate change is causing more unpredictable weather patterns, longer periods of drought and increased fluctuations in temperature which is causing cities to reevaluate their resiliency. In thirty years, the climate of the northeastern United States is going to be much different than it is today. In order to adapt to the realities of climate change in our future, we need to plan to have resilient urban flora that is both ecologically-productive and aesthetically-pleasing. Landscape architects, policy makers and municipalities need to better understand the technical complexity and economic output required to realize those visions. We need to promote vegetation within our cities that will allow us to use less water for irrigation, subsist with relatively little maintenance and be self-replicating in a way that requires very little oversight. Every possible surface in the city – the walls, the streets, the roofs, the edges, the remnant vestiges and the vacant territories – are areas to colonize and opportunities to be utilized. As we plan for more livable resilient cities, how can we do so with an eye towards sustainability, management and fiscal responsibility? How can we incorporate more green spaces into our urban environments while minimizing our installation, maintenance and operational costs for these green spaces?

Designing with Weeds

As we begin to better understand the art historical precedents, themes of landscape urbanism, and the way that wandering in our contemporary city can help us reframe perceptions, we can draw on our knowledge to design a sustainable urban future. Careri writes, “…walking is useful for architecture as a cognitive and design tool, as a means of recognizing a geography in the chaos of peripheries, and a means through which to invent new ways to intervene in public metropolitan spaces, to investigate them, and make them visible.”[ii] From our perspective as landscape urbanists and designers, there is a need to reveal the potential of our spontaneous urban landscapes and create a dialectic about their value and beauty.

By utilizing wild urban plants, we can design with a palette of greenery adapted to disturbed soils, widely available, and attractive to pollinators and other wildlife. An informed combination of these factors can help create a pleasant urban meadow. As much as the upfront plant selection needs to play an important role, some designing will come through the process of subtraction. By removing diseased plants, those planted too close together or even the plants that are particularly unsightly or cause allergic reaction, designers can help to make the wild urban meadow tidy and kempt – and more appealing. Through processes of subtraction, addition, optimization and replication, the patchwork ecology of widespread spontaneous vegetation will enable the emergence of a more resilient, adaptable, and sustainable urban future.

In operating on the city, our architectural strategy at Future Green Studio is to analyze its social, ecological and historical systems, draw conclusions that allow us to develop a set of typologies or a kit of parts that can be rolled out on the city in ways appropriate to the site specific conditions, the inherent sensibilities and psychogeographic dynamics of the city. We need to recognize the small-scale interventions of green infrastructure where traditionally underutilized spaces – like walls, roofs and streets – can be utilized in innovative ways to create both aesthetically and ecologically performative spaces. These micro-interventions together through their aggregation become a functioning ecology that helps to create a more livable and sustainable city.

In order to understand the future of ecological urbanism as we encounter climate change, we are going to have to study the vegetative systems that are most successful now in our harshest urban conditions. These weeds are the first invaders of a radical new nature that subverts from the ground up the autocratic systems of urban renewal we like to call “progress.” In this case, traditional perceptions are meant to be broken. There is no original nature to preserve. Nature is by its very existence a dynamic force that is constantly reinventing itself.

We’ve evolved through history understanding these layers of nature that exist between ourselves and the world around us. Traditionally the horizontal juxtaposition of artifice to nature – from house, to garden, to fence, to fields, and then to the distant mountaintop – unfolds and stretches out across our view. As we move into the 21st century, what we are now beginning to understand is that because we’ve colonized nearly everything, that sense of the sacredness of first nature is disappearing. At the same time, perhaps there is some sort of inversion that is happening as we look for that first nature from within. Completely intertwined with our urban territory, spontaneous plants are the foundation of our future garden cities. Maybe that sacred wild is emerging right underneath our feet?

References

[i] Francesco Careri, Walkscapes (Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, 2003), 26.

[ii] Ibid.

About the Author

David Seiter is design director and founding principal of Future Green Studio – a design-build firm specializing in landscape urbanism and ecology. David’s design portfolio encompasses award-winning private and public-use projects. His design work was nationally recognized with the 2018 Emerging Voices Award by the Architectural League of New York. He is author of the book Spontaneous Urban Plants: Weeds in NYC – a book about the overlooked ecological value of weeds in the urban landscape. Additionally his research into urban adapted plants won a 2015 National Honor Award in Research from the American Society of Landscape Architects. David holds a MLA from the University of Pennsylvania and is a licensed Landscape Architect in New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia.

David Seiter is design director and founding principal of Future Green Studio – a design-build firm specializing in landscape urbanism and ecology. David’s design portfolio encompasses award-winning private and public-use projects. His design work was nationally recognized with the 2018 Emerging Voices Award by the Architectural League of New York. He is author of the book Spontaneous Urban Plants: Weeds in NYC – a book about the overlooked ecological value of weeds in the urban landscape. Additionally his research into urban adapted plants won a 2015 National Honor Award in Research from the American Society of Landscape Architects. David holds a MLA from the University of Pennsylvania and is a licensed Landscape Architect in New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement.Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.