by Bryan Quinn

Too often matters of convention hold back the creative process. In the landscape, where I primarily work, sometimes my best-intentioned clients initially cling to design clichés such as lawnscapes, overly simplified plant palettes, off-the-shelf garden ornaments, and other types of requests that come from a limited paradigm. In response, I use a two-step method to break through and find deeper ground where I can pursue my craft.

First, I show my potential client examples of my own built work and that of others. This approach develops a shared language between myself and the client so we can focus on what they want, rather than what they know. This normally takes very little time and can be easily done before we are formally engaged in a commission. It also helps me vet my clientele to ensure I am working with someone with whom I stylistically agree.

My second step is typically to build a site model. Three-dimensional model building is fundamental to my design process. I have found these 3-D constructions to be extremely successful over the years. While the exact materials and size of each model varies, our studio always keeps jugs of Elmer’s glue and 30” x 40” sheets of corrugated cardboard close by. Our conference table doubles as a model making table, and we proudly display past models on our walls.

Here are my ten reasons for creating 3-D models:

1. Developing a Better Understanding of the Land

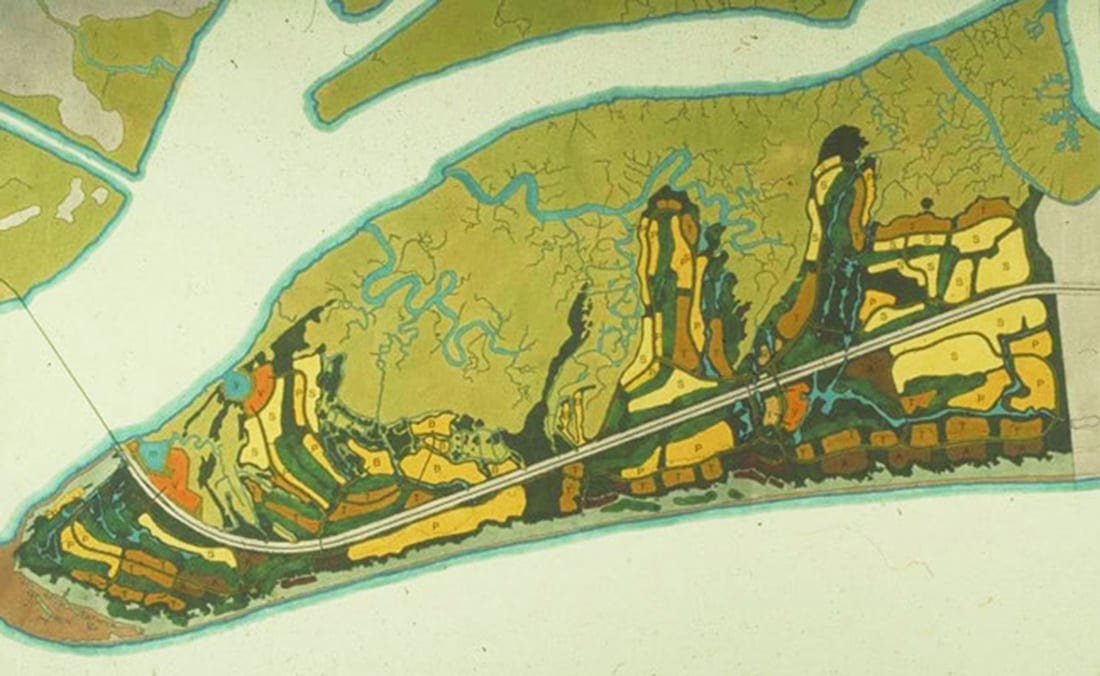

The model making process drives our site analysis. In our studio, we combine drone photography, geospatial mapping, field collected data, and topographic surveys to quickly create scaled plans of existing conditions. This process is greatly influenced by the work of the late Scottish Landscape Architect Ian McHarg, who wrote the highly influential book Design With Nature. McHarg and his team of assistants famously would work on large mylar sheets to create scaled maps of soils, habitats, topographic relief, and other environmental features. These semi-transparent sheets would then be layered to create a combined map of a landscape.

This plan by Ian McHarg for Amelia Island, FL was developed by overlaying a series of environmental maps that defined land use patterns. Image Credit: Wallace, McHarg, Roberts and Todd (now WRT, LLC).

In the process of building a 3-D model, we almost always focus on topography to create a base, which normally also captures drainage patterns and viewsheds as well. We then overlay selected environmental layers, either by gluing or adding materials, to the topographic base. The result is a solid three-dimensional map of existing conditions, which we can later build into with our proposed design.

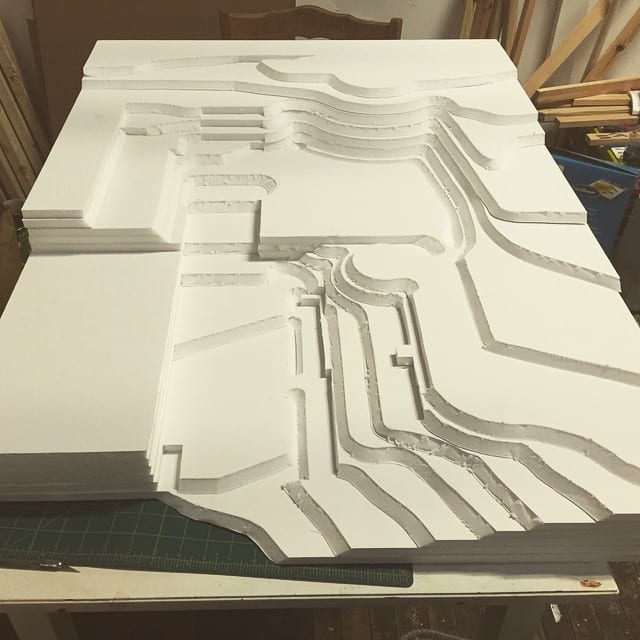

We use QGIS, a geospatial map making software, to obtain elevation data. We then translate that data to a contoured plan which we trace and cut using Xacto blades and spray mount. The model shown here required a lot of vertical topography. This was one of our larger models at 60″ x 80″ so we added sheets of rigid foam to the base to lighten the weight.

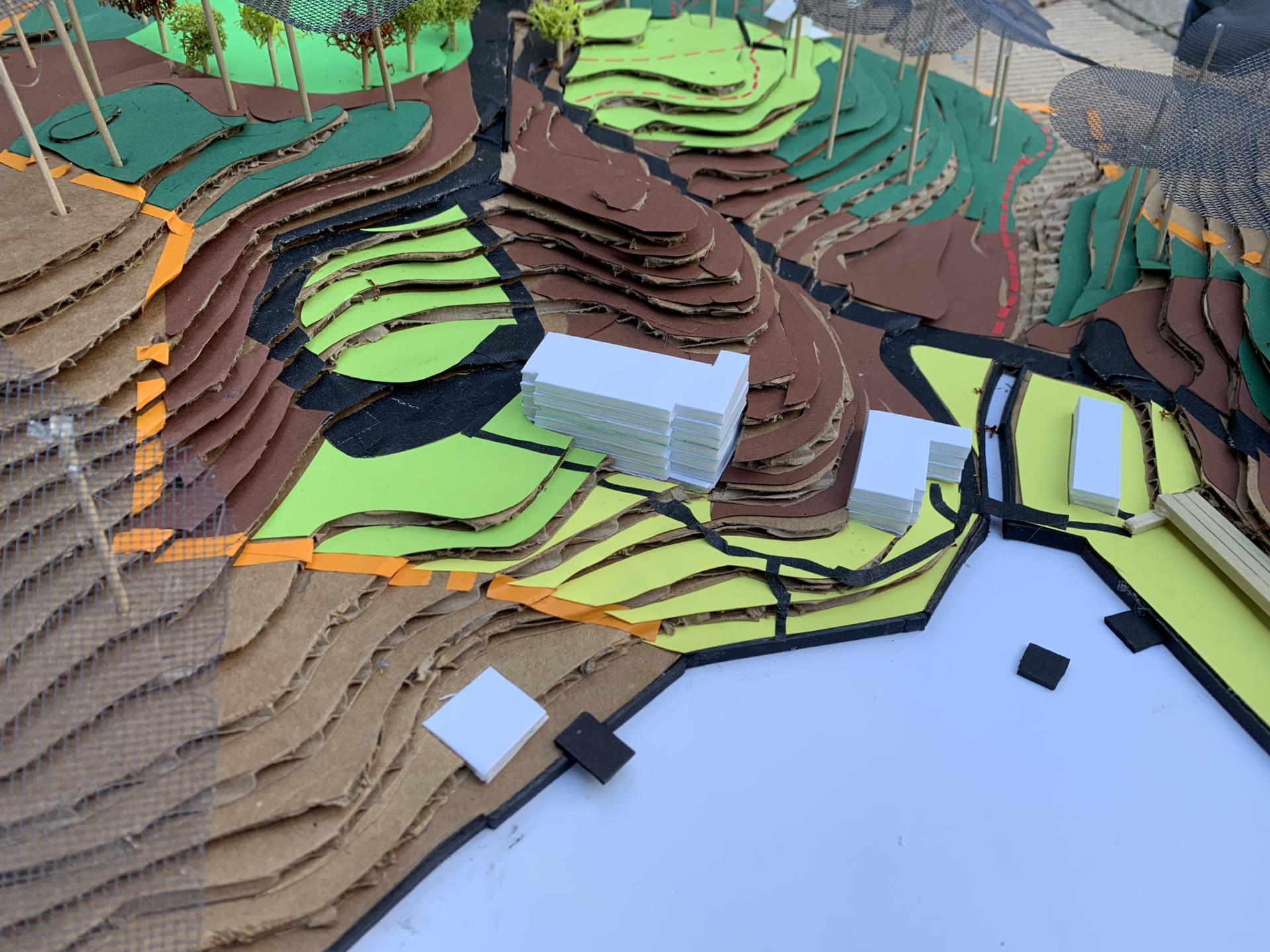

This existing condition site model for a 70-acre agroecological master plan project shows numerous environmental features including: topography, intermittent streams and their buffers, forest, and differently aged “old fields.”

2. Demonstrating Commitment

To make a living as an environmental artist I have to charge hourly fees for my time. These fees are often at the front end of a commission and require a lot of faith on behalf of the client that their money is well spent. We are able to show progress to the client early and often through model making. The blood, sweat, and tears put into these models is evident. Very little is hand built in 21st Century society and our clients tend to appreciate the commitment shown in a carefully crafted representation of our shared vision for their landscape, especially early in the project.

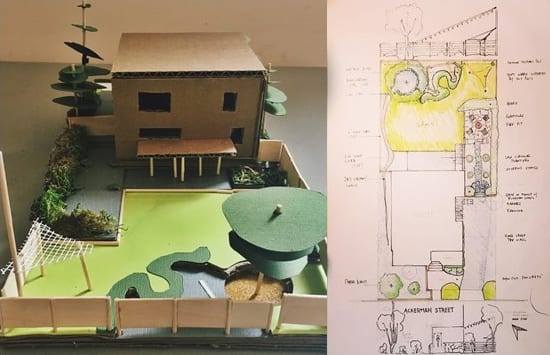

This combination of simple model and plan sketch benefited our own creative process, but also helped show the client early progress towards their new garden during a project kickoff meeting.

Here we used only cardboard, graphite, and tracing paper to convey the design intent. We later developed a color cardboard collage based on the forms created in the original model. Between these two creations the client gained a full picture of our artistic intent.

The well-known designer Roberto Burle Marx pioneered the use of curvilinear abstractions of plantings to convey design intent. Shown here was part of his plan for a rooftop garden. Image Credit: Burle Marx and Cia. Ltda

3. Generating Creative Ideas

The conceptualization of the model itself is a great way for the designer to deeply explore the site at hand. The modeler can employ landscape ecology principles to consider different ecological systems within the landscape, how they function, and how they relate to each other. S/he must consider each site feature, and how the removal or addition of new features will affect the surrounding ecological systems. Additionally, the designer must consider how the removal or addition of elements might affect the interactions of humans with the landscape. An environmental designer may use a model to examine certain questions: How will the addition of tree plantings impact adjacent habitat? If a pedestrian bridge is raised by three feet, how much of a viewshed will be opened up?

It can be difficult to convey the intent behind ecologically-inspired designs. Large ideas like landscape corridors, landforms, and hydrology are sometimes confusing to the layperson. Even in two-dimensional graphic plans, such real-world conditions often appear abstracted and confusing. In order to better illustrate big ideas, I often generate initial drawings and site maps specifically to create scaled, three-dimensional models. These models can depict topography, viewscapes, plantings, and buildings in a way that can help people better understand the concepts behind my work.

Two-dimensional drawing, even abstracted, cannot portray the intent of design as accurately as a three-dimensional model. 2-D drawings lock viewers into a specific position and trap them in a particular state of observation. 3-D models, however, allow immediate visual interaction. The viewer can walk around a model for an aerial perspective or crouch down and view the ground plane as it might actually look in the built design. Simultaneously, a well-composed 3-D model gives the viewer an omnipresent feel by provide surrounding context to the design such as forests, buildings, landforms, and uses.

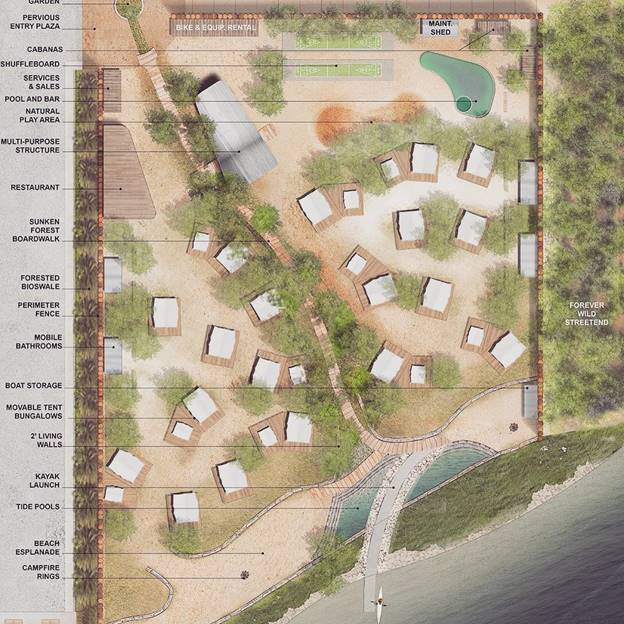

This site model for Camp Rockaway, a new “glamping” destination in Queens, was sequentially layered with cardboard (in our minds sand) to create a sunken forest trail within a larger native dunescape. Tidal swimming pools, shown in the foreground by white museum board, are bisected by a kayak boat launch. These concepts, while simple in nature, create real experiences for the viewer and also for the engineering team responsible for converting our concept to a feasible design.

The model for Camp Rockaway led directly to this conceptual rendering. The rendering shows many details not in the model, but the basic forms and identity of the land we created in the model helped us to collaborate with the rest of the project team to layer additional site features.

4. Focus on the Big Picture

A model is a great way to present a design to a client in an easily understood and accurate format. It allows the client to clearly visualize the changes and developments that the designer is envisioning, and aids the conversation and collaboration between the client, project team, and designer. Used during presentations, 3-D models help us communicate with clients and enhance the ability of the design team to think creatively about a site.

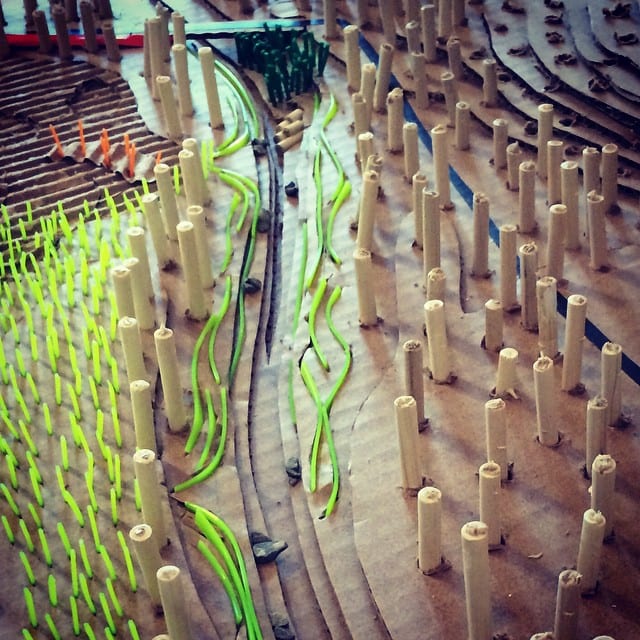

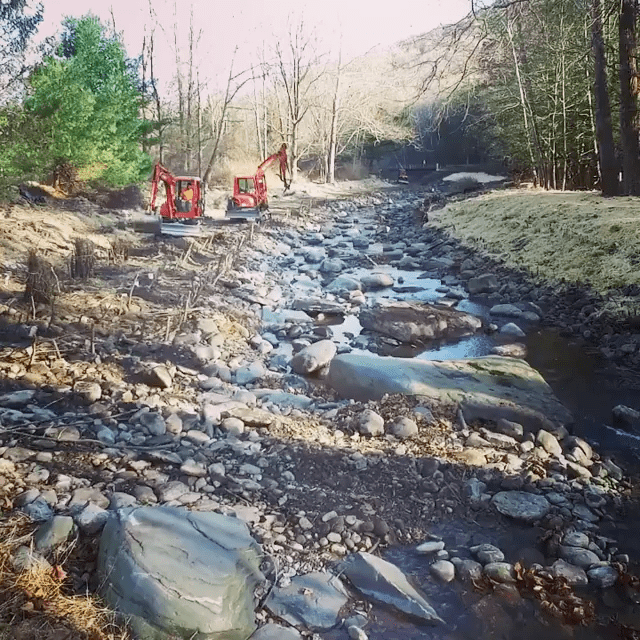

This site model was built to explore different bioengineering options for a Catskill stream restoration. We used zip ties, wooden dowel stubs, and pieces of weed whacker cord to denote different types of plantings. Each material showed a different bioengineering technique; the species and number of plants was not necessary to show and would have been a distraction to the design intent.

Shown here during construction, the layout of the plantings was directly informed by the earlier site model.

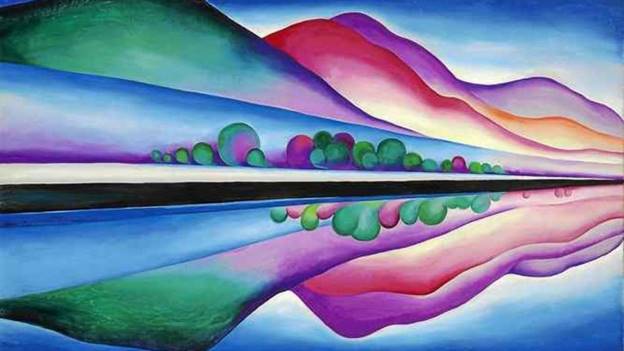

The true feelings one experiences from a landscape view is more than can be expressed in a photograph. This painting of Lake George by Georgia O’Keefe rings true despite its departure from photorealistic colors. Our models employ a similar method by abstracting different habitat zones into ultra-saturated colors.

5. Simplification

It is too easy to get bogged down in details while working on very large landscapes. By carefully selecting the scale and materials we use, we can keep the model vague in areas that might otherwise be distracting. For example, a woodland trail can be represented with dots of red masking tape. This does not mean the trail is intended to be red stepping stones, instead it means that the specifics of the path are not figured out yet, or that the materials of the path are much less important than its route and relationship to surrounding plant communities. In this case, models help clarify complex situations by eliminating extraneous or less important elements of the design.

For example, in stream restoration projects, a model is able to clearly depict any underwater or partially submerged features along with the slope and depth of the stream bottom. It will also show vegetation around the stream banks. It’s difficult to show these aspects of a project accurately in 2-D drawing.

This very simple foamcore model perfectly described the artistic intent behind our work for a new public park. Originally a sloped vacant lot, we wanted to show a series of distinctive spaces defined by the relationship between earthwork and the movement of storm water through the new park. The simplicity of this concept model made it easy for the consulting engineers to create the required grading and paving plans.

Shown here during construction, the same forms envisioned in the model are being built by our landscape construction team.

Now built, the new park reflected the simplicity of the original concept. Using plants from our own nursery, we added an element of complexity and interest through managed ecological succession.

This before and after grading plan, created by the project’s engineer, served a very important purpose for the project. But these plans do not work to convey artistic intent, especially to the layperson.

6. Team Building

Because our team’s ideas often require significant modifications to large spaces, we sometimes require the services of a diverse set of other consultants such as architects, civil engineers, landscape architects, planners, land use attorneys, and other professionals to advance our projects. A well-made site model allows them to immediately understand our initial concepts. It also sets the tone that our work together will be something truly special when compared to their usual day-to-day jobs. For example, an engineer might spend most days designing retaining walls, septic fields, parking lots, and other un-inspiring projects. But when we enter a meeting and set down one of our three-foot by four-foot cardboard creations on the conference table, the mood immediately shifts for the better, and the professionals I work with tend to become more engaged. We also end up saving a lot of time by simply pointing to locations of concern directly within the model, rather than sorting through complex engineering drawings that show different conditions according to the function of the individual drawing.

This model for a new park entryway and accessible trail system helped show a partner community group how a new path would integrate into the existing landscape without causing significant damage to the forest.

Shown here during construction, the actual build project is on track to nearly match the model’s instructions. Shallow digging and meandering between existing trees created a very small project footprint.

7. Public Presentations

Some, but not all, of our work is in the public realm. Public projects often involve a stage of community input and dialogue which requires us to provide a clear explanation of our design to groups of community members and/or stakeholders. During presentations, models provide a visually engaging centerpiece that everyone in the room can focus on, discuss, and learn from. Kids love them, too!

This concept we developed for a new theater, kids day camp, and artist studios along the banks of a creek relied heavily on subtle elevational changes relative to the flood plain and future sea level rise predictions. The model was then used as part of a fundraising campaign and part of the client’s submission to the town planning board.

Working for participating clients, collaborators, and the public often requires us to share general ideas before arriving at the fine details of a project. This interior model view of a proposed council ring beside a patch of highbush blueberries gives even the layperson a sense of artistic intent without getting stuck in minor details, which can be figured out later.

8. Generating Two-Dimensional Graphics

A well-made model can lead to specific critical views needed to advance and describe the design visions. These critical views can be plans, like in the overhead view of a model we made for Vassar College’s Farm and Ecological Reserve. This view allows viewers to quickly understand the topography of the landscape, as well as how proposed features will fit into the existing conditions. Another type of critical view is a perspective, like the image below, which shows a bird’s eye view of climate change impacts to a property on the Hudson River. Perspectives allow clients to focus on specific features of the design plan and get a feel for them early in the process. Ultimately, the multiplicity of scales and perspectives provided by our models give clients a deeper understanding of their future landscape.

This image was created using a model photograph and Adobe Illustrator to show the impact of a two-meter rise in sea levels. We were able to do this quickly and effectively in our studio because this scaled model was based on recent LIDAR data.

This model was created by gluing an aerial photograph to an exaggerated cardboard topography. As we progressed through our creative process alongside our client and their stakeholders, we began adding new programmatic elements and re-orienting existing features. Once complete, we photographed the model from directly overhead to create the illusion of a scaled plan. This approach led to a really compelling aesthetic style which we have replicated often since then. It also saved us time and money!

9. Building Efficiency

We are not just designers, we are also builders. The tactile relationship we gain making a model can directly transfer to the field. And on rainy days we can bring our construction workers into the studio to keep busy and participate in the creative process without the vast technical training needed to make a really good computer rendering. Our experience is that the building portion of our design-build projects becomes more meaningful and efficient when the people building it are involved with the design process.

This model for the redevelopment of a lakefront retreat abstracted different habitat types based on their construction requirements. For example, the different shades of yellow and green reflect habitats that would be planted, whereas areas shown in dark brown would become “let it grow” rewilding areas. The clear distinction of the different planting zones (from yellow to dark green) led to a very efficient construction sequence with the architect, engineer, and excavator. As a result, we were able to produce and deliver the required plants zone by zone.

10. Less Screen Time

Models were once much more widespread in the architecture and engineering industry. More recently, 3-D computer modelling software has become the preferred method of representation. But the value of a physical model is a craft our studio has found exceptionally rewarding. Working on a computer screen without scale simply cannot compare with the fixed dimensions required by hand-made work and the self-determined orbital experience of an independent viewer. For every brilliant computer-created model or rendering, there are hundreds of sub-par creations. This is not to take away from the importance of computers in design, only to say that viable alternatives exist.

Many people experience monotony and health issues from computer-based work. Screens can really kill creativity. Our studio has found improved worker productivity and job satisfaction through reduction in screen time. Often, we have two or even three people working on a single model while engaging in ongoing discussions about a wide range of important topics.

Last but not least, even if the project is never fully realized, which is too often the case, working through ideas in model form creates real results in the form of art. Our models embody hundreds, sometimes thousands, of hours of devotion, discussion, and research. Once in a final form, we can continue to build off the principles they embody for other projects.

We use work spaces like this one to create an ergonomic and creative environment where our team can shift seamlessly between different mediums of design such as digital, hand drawn, and model making.

Interested in building your own models?

Here’s a helpful list of materials to get you started:

- Xacto Blades (lots)

- Corrugated cardboard sheets (these can be ordered fresh or re-used Amazon boxes)

- An appropriately sized cutting mat, larger than your largest sheet of cardboards

- A jug of glue, spray mount, and glue stocks

- A printer capable of large format or tiling

- Colored card stock

- Wood dowels of varying dimensions

- Masking tape in a wide variety of colors

- Gesso and acrylic paint

- Foamcore, chipboard, museum board, or other thick paper types for integrating with the cardboard

- Foam and hot wire foam cutter

About the Author

Bryan Quinn’s lifelong dedication to landscapes, people and the environment is evident in his diverse body of work including gardens, parks, campuses, farms, re-wilded land, and urban design. Part scientist and part artist, his activist design methodology relies on a sensitivity to the local qualities of land. Regardless of project scale, Bryan strives to bring out the potential for every project to inspire people with ecological and design principles. He is the founder of One Nature, a vertically integrated and mission-based business that addresses the global environmental crisis.