by Alex Krofta

The “Expanding Riparian Forest Buffers” project is being led by the Merrimack River Watershed Council (MRWC) in partnership with Nashua River Watershed Association, UNH Cooperative Extension, and MassDCR. The three main phases of the project are 1) Prioritization of seven HUC12 subwatersheds for protection and restoration; 2) Outreach to towns and landowners about the project and the importance of buffers; 3) and Implementation of native planting projects along critical streams.

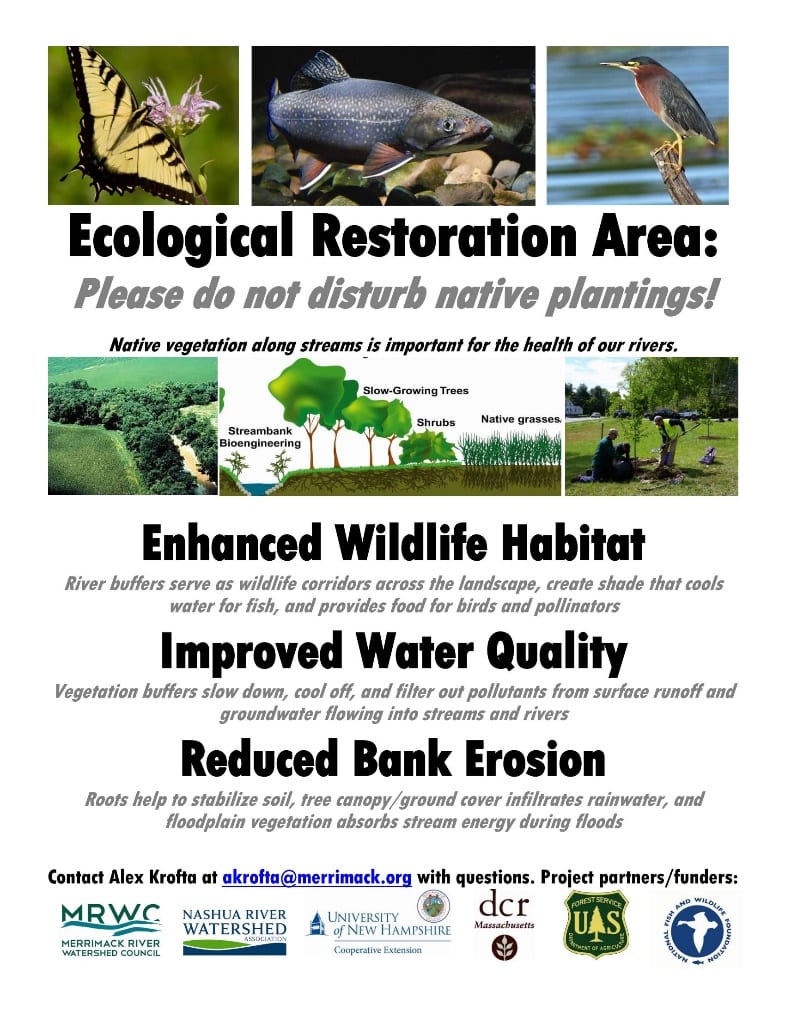

An expanded, diversified riparian buffer at a park in New Hampshire. Staff and volunteers planted sycamore, willow, elm, black gum, blueberry, steeplebush, alder, Joe Pye weed, swamp milkweed, aster, big bluestem, wild rye grass, and other native plants to protect water quality and enhance wildlife habitat.

“Riparian Buffer..?” Riparian is an adjective meaning “relating to or situated on the banks of a river.” The intent of this project is to increase the length and width of the vegetated “buffer” along key streams – that is, to plant and/or expand the strip of native trees, shrubs, grasses, and wildflowers.

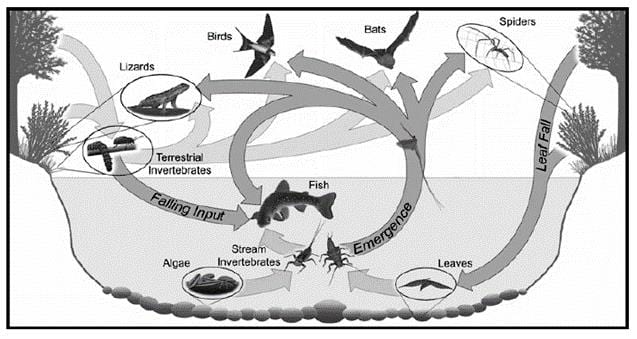

Water Quality Benefits: Riparian buffers protect water quality in a number of ways. As rainwater moves over the ground surface to streams, plants slow the flow and filter out sediments and pollutants. Vegetation helps reduce the amount of surface flow by increasing the infiltration of rainwater into groundwater. The roots of plants, as well as the leaves and branches that fall along and into the stream, create habitat for microorganisms that “eat” toxic pollutants and excessive nutrients. Vegetation drives down water temperature, an important water quality factor, by casting shade on streams and by recharging more precipitation into the cooler groundwater.

Hydrologic Benefits: It’s easy to see how a thick tangle of roots along a river bank hold the soil and prevent erosion. But riparian vegetation is also critical during floods when floods top the banks, because trees and shrubs help to dissipate the energy of the rushing flood waters. Intact floodplain wetlands store large amounts of water and sediment as well, protecting buildings and infrastructure downstream.

Biodiversity: As the “ecotone” between two distinct habitats – dry uplands and the river – the naturally vegetated riparian buffer hosts a great diversity of wildlife. It’s long, linear shape also provides a migration corridor across the landscape. Through a web of interactions, the riparian buffer is also critical to species that inhabit the uplands or the river exclusively. A brook trout, for instance, uses fallen logs for in-stream cover and eats hapless forest insects that fall into the water from overhanging branches. Forest-interior birds, in turn, raise their young on insects that breed in the stream and emerge as adults on riparian vegetation. As floodwaters shape the riparian zone and deposit rich sediments across the land, unique natural communities that occur nowhere else are formed and flourish.

Carrying Out the Project

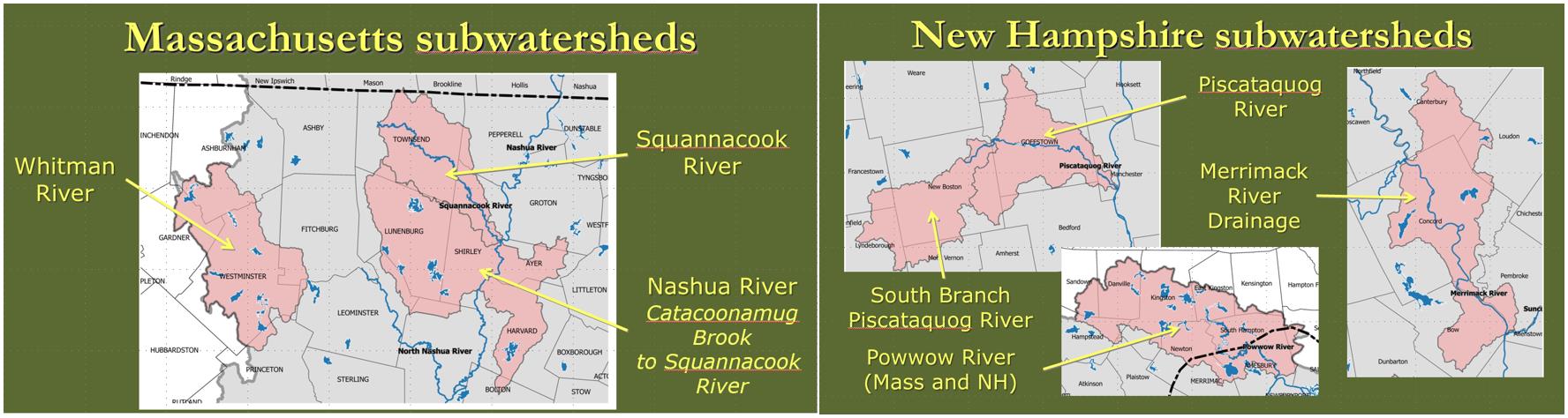

Prioritizing Focus Areas: The level of analysis was the US Geological Survey Hydrologic Unit Classification 12 sub-watersheds. In plain English, USGS HUC12 sub-watersheds are just smaller, tributary-sized drainage areas of a larger watershed. To select HUC12s for protection and restoration, MRWC began with the percentage of impervious cover in each HUC12. When 5-7% of a watershed is converted to impervious cover – buildings and pavement – the watershed becomes impaired, meaning water quality, hydrologic function, and wildlife habitat begins to decline. MRWC selected all the HUC12s in the Merrimack watershed that were at this threshold, and then refined the selection further based on water quality threats from land use types, projected development pressure, rare species occurrence, and unique habitat types. Seven HUC12 sub-watersheds were selected as focus areas in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Finding Planting Sites: To find good planting sites within the focus areas, staff first took a bird’s eye view, using GIS data and aerial photos to look for points along the stream that were lacking good buffers. In addition to this approach, many sites were found during the outreach phase and through networks of local contacts. On-the-ground knowledge of these areas yielded good results, as members of the community shared their knowledge and volunteered their land for restoration.

Site Design: These planting sites are primarily functional – they are intended to provide water quality, hydrologic, and biodiversity benefits while sustaining themselves with minimal maintenance beyond the initial planting and subsequent watering. They are meant to become part of the natural landscape, with their main aesthetic benefit being a “naturalized” and intact strip of native plants along the stream.

Plant Selection: Riparian landscapes are very diverse. Though uniformly defined by some linear distance (in our case, 300 feet) from the edge of a stream, the factors affecting habitat within the buffer – topography, aspect, soil type, moisture, and land use history – vary widely. Plants range from dry upland species like pitch pine and sweet fern to wetter species like silver maple and steeplebush Spirea. To determine which species are appropriate, an initial site visit is conducted to see what’s already growing nearby. If the site is heavily influenced by human activity (erosion, compaction, trucked-in fill), hardy and adaptable species like red maple are favored. In general, “hardy and adaptable” is a good rule for these highly varied and dynamic sites. Species are also selected for wildlife benefit, floristic diversity, and aesthetics appeal.

Plant Material: In most cases, small and inexpensive plant material is used. This includes landscape plugs, bare-root seedlings, and small containerized saplings (known as “whips”). These small plants are more adaptable to new conditions than larger trees or shrubs, which is critical for sites where maintenance capacity is minimal. Though not all the bare-root seedlings will survive, the investment is negligible. Smaller plants are easier to transport and easier to plant, especially with volunteers. Smaller plants, though, lack the immediate visual impact of a 1.5”-caliper tree, and in some cases larger stock was used.

Planting Effort: Staff, volunteers, and occasionally landscape contractors (generously supplied by landowners) do the work of getting plants in the ground. On small, private, or hazardous (read: excessive poison ivy) sites, staff takes care of the planting. When appropriate, a team of volunteers is assembled to dig holes, amend soil on sandy sites, and water-in the new plants. If needed, larger trees are mulched. If beavers are an issue, small fences are erected around tasty new trees.

Planting Site Descriptions

Commercial Sites: We’ve restored buffers on three commercial sites in Massachusetts. These sites include two large areas of lawn converted to trees and shrubs, and the unused edge of a compacted gravel parking lot planted with everything from swamp white oak to soft rush. Commercial sites may have resources to contribute, in terms of contractor time and other financial assistance, that may be unavailable to other landowners. Depending on corporate structure, securing approval can either be a cinch…or not possible.

Municipal Sites: School grounds, a gravel parking lot, a town park, and a DPW yard are some of the municipal sites that have been restored. These projects can benefit from the equipment and labor resources available to towns. These restorations can also compliment ongoing town efforts for environmental stewardship, like when our restoration dove-tailed with the DPW’s new stormwater improvements to protect a small brook. Public sites are also highly-trafficked, adding an outreach component to the benefits. Excellent communication, we’ve found, is KEY to ensuring that all relevant town departments are aware of the project and on-board with its goals.

Residential Sites: One restoration has been completed in a residential yard, on a patch of lawn along a beaver swamp. Though a small and private site, the landowner can give the plants more care and attention. They also have a front-row seat as the plants grow and the ecosystem responds to the improvements. Future residential plantings may be a valuable outreach tool.

Recreational Sites: An eroding swimming hole and a popular skating pond are the site of two restorations. Recreational sites must balance the needs and expectations of users with protecting resources – this means blocking off certain portions of the bank while maintaining some access. It also means clearly communicating, through signs and outreach, the purpose of the project. We were pleased to find that most people value these places, and therefore embrace our efforts to restore them. Some locals even took to watering our plants on hot days.

“Agricultural” Sites: On the New England landscape, riparian areas and floodplains have been great agricultural resources due to the rich alluvial soils and flat terrain. Because of the relative scarcity of this valuable agricultural land, it’s been difficult to find agricultural land suitable for reversion to riparian buffers. Two successful sites are on conservation ag land set aside for open space and wildlife habitat, and therefore not subject to the same economic pressures of other agricultural operations. These are the two largest restorations completed however, around an acre each, and will have tremendous benefit for rare species and erosion control. MRWC will be working with Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to identify and implement more agricultural buffer restorations going forward.

Ongoing Support

Major funders are the US Forest Service and National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, with additional foundation support from New Horizons, Agape, and Patagonia. This project is ongoing! If you know of a good site for restoration in the Merrimack River watershed – especially in or near one of our focus areas – please get in touch! MRWC has funding for plant material and does installation with staff and volunteers, at no cost to landowners.

About the Author

Alex Krofta studied Environmental Science and Policy at Clark University before spending many years as a wildlife field-technician in the swamps and streams of Upstate New York. He has worked as a conservation lands steward for Mount Grace Land Conservation Trust in Athol and as a habitat management planner and practitioner with Polatin Ecological Services/Land Stewardship, Inc. He completed a MS in Sustainable Landscape Planning and Design at the Conway School in June of 2015, and joined the Merrimack River Watershed Council in 2016 as Restoration Scientist for the Expanding Riparian Forest Buffers project. He recently took on a new role as Stewardship Specialist in MassWildlife’s Connecticut Valley District, but continues to stay involved with MRWC. For more info on this project, he can be reached at akrofta@merrimack.org.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.