The best food plants for insects, with a focus on caterpillars and bees

by Thomas Berger

When choosing plants to support insects in our gardens, we want to make the most of our limited space. Which plants nourish the most species? And which kinds of insects need our support the most urgently?

Two groups of insects are of particular importance: the caterpillars of butterflies and moths (lepidoptera) are an important part of the wildlife food chain, and the pollinators, especially native bees, fulfill the essential function of pollinating not only our food crops but also native plants and thus contribute to their survival.

Many insects are not picky about their food sources and can nourish themselves from a relatively wide variety of plants. These generalists are easy to please. However, other insects are specialized on only a very narrow selection of species, often in the same genus (monolectic specialists), on which they depend. Lack of these plants will threaten the survival of these specialist insects.

Our goal should be to provide habitat for the largest possible number of insect species, including as many food specialists as possible, as many of these suffer from strong declines.

Identifying the Best Plants

The following plant recommendations are based on the results of studies about lepidoptera food plants by Doug Tallamy and about bee food plants by Jarrod Fowler and Sam Droege. The list of the host plants for caterpillars was compared to the list of plants needed by specialized bees, and those plants that occurred in both lists were given special attention.

Of all plants studied by Doug Tallamy, he found that the oak supports the most caterpillars; however, oaks are wind pollinated and therefore of no use to pollinating insects. Also, oaks are generally large trees and the focus of this recommendation is on smaller plants, shrubs, and herbaceous perennials that can find space in our tight urban backyards.

Among the woody plants, and disregarding the oak, the genera Salix (willows) and Prunus (cherries and plums) are the most important caterpillar food plants. Salix is also the number one plant that supports bees, hosting the highest number of dependent specialized bee species, whereas Prunus is important for generalist bees. Vaccinium (blueberries and cranberries), the number two woody plant for specialized bees, is also highly ranked in the lepidoptera list.

| Table 1: Best woody plants for insect gardens | ||||

| Rank | Plant Genus | Supported Species | ||

| specialist bees | lepidopteran caterpillars | |||

| 1 | Willow | Salix | 14 | 456 |

| 2 | Blueberry and Cranberry | Vaccinium | 9 | 288 |

| 3 | Dogwood | Swida (formerly Cornus) | 4 | 118 |

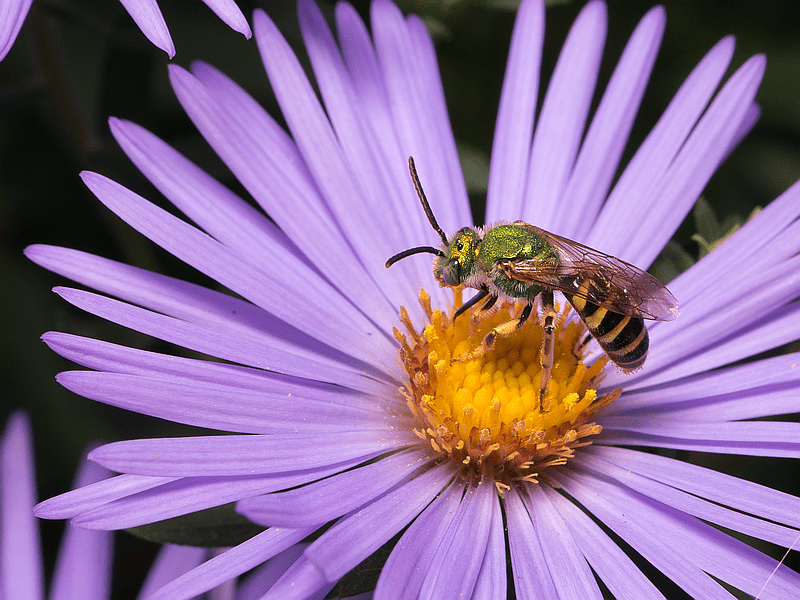

The overlap of herbaceous plants in the two studies is even more striking. Goldenrod (Solidago), Aster (Symphyotrichum) and Sunflower (Helianthus) are ranked number one, two and three in both lists! As we all know from watching insects in our gardens, these same plants are also highly attractive to generalist pollinators, including butterflies, flower flies, and solitary wasps.

| Table 2: Best herbaceous plants for insect gardens | ||||

| Rank | plant genus | supported species | ||

| specialist bees | lepidopteran caterpillars | |||

| 1 | Goldenrod | Solidago | 11 | 115 |

| 2 | Aster | Symphyotrichum | 7 | 112 |

| 3 | Sunflower | Helianthus | 7 | 73 |

These “superfoods” for wildlife should be used in abundance in our gardens. However, some of the plants described in the following text have no history of garden use and might require an open mind for unconventional design. A few of these plants are also not commonly found in the nursery trade, and surely some experimentation will be needed. The less attractive species might not be considered worthy of use around the house, but we should still try to incorporate them into our surroundings wherever they fit – be it a transition planting between garden and woodlands, near a wetland, or in the backyard meadow.

Several Mining Bees (Andrena) are specialized to gather pollen for their larvae only from Goldenrod species. Photo: Thomas Berger

Recommended Willow Species

Willows support an astonishing number of both lepidopteran caterpillars and specialist bees. Bee keepers frequently plant willows near their hives to provide pollen and nectar early in the season, but many other species of bees, flower flies, ichneumon wasps, and beetles make use of this early food source.

The foliage and other plant parts provide food for grubs of native long-horned beetles and leaf beetles, plant bugs, aphids, leaf-hoppers, and the caterpillar-like larvae of some sawflies – all of which are also food for birds. Among the lepidopteran caterpillars are those of some well-known butterflies like the Viceroy (Limenitis archippus), Red-spotted Purple (Limenitis arthemis astyanax), Mourning Cloak (Nymphalis antiopa), and Compton Tortoiseshell (Nymphalis vau-album).

The superfood status of willows is further confirmed by many vertebrate animals that eat the buds, seeds, foliage, twigs, or bark of willows. These include Wood Turtle and Snapping Turtle, Ruffled Grouse, rabbits, squirrels, muskrats, beaver, deer, elk, and moose.

Willows are dioecious, and it is necessary to plant male and female plants to best serve the bees. Seeds are viable only for a short time and need to be used quickly! Propagation by hardwood cuttings late winter is usually successful. Use cuttings from male and female plants. Willows can be pruned as desired, and some species are traditionally harvested for basket making.

Prairie Willow is adapted to dryer soil and might be a good choice for the average garden. Photo: Donald Cameron, https://gobotany.newenglandwild.org

The following willows are possible candidates for garden use. Recommendations are somewhat tentative, as there is little documented experience with these shrubs as garden plants.

| Table 3. Willows (Salix) for Garden Use | ||

| bebbiana | Long-beaked Willow | adaptable, used for re-vegetation |

| discolor | Pussy Willow | sometimes planted in gardens and by bee-keepers |

| rigida

(sometimes incl. under eriocephala) |

Heart-leaved Willow | a widespread species and important wildlife plant; ‘American McKay’ is a clone selected for use in basket making. |

| humilis | Prairie Willow | 6-12 ft. more drought tolerant than other species, seed is available by Prairie Moon Nursery |

| occidentalis (syn. humilis occidentalis) | Dwarf Prairie Willow | more compact, and naturally found in dry locations such as barrens, fields and woodlands |

| pyrifolia | Balsam Willow | red stems – might be hard to find, needs moist sites and lime, but might be worth checking out for gardening potential |

| sericea | Silky Willow | large shrub with attractive silvery foliage |

| uva-ursi | Bearberry Willow | trailing, 3″ high, for rock gardens |

Of these willows, the Dwarf Prairie Willow might be the most suitable for the average smaller garden.

It is unlikely that the non-native willows are used in the same way by native insects, and should therefore be avoided. Alien species that are found in the nursery trade include Salix alba ‘Tristis’, S. caprea ‘Pendula’, S. integra ‘Hakura Nishiki’ , S. melanostachys and S. purpurea ‘Nana’. Alien willows found in the wild are S. cinerea and pentandra.

Recommended Vaccinium Species

Blueberries are extremely valuable wildlife plants, whose nectar and pollen, berries, and foliage nourish a wide range of animals, including many generalist and specialist bee species, and the caterpillars of various elfin, comma, sulfur and hairstreak butterflies. The berries are a cherished garden crop, but are also favored by many birds and mammals, including Eastern Bluebird, Cardinal, Catbird, Wood Thrush, Oriole and Scarlet Tanager, as well as bear, fox, raccoon, and skunk. The twigs are browsed by deer and rabbits.

Since several kinds of blueberries are common garden plants they are easy to find in the nursery trade. Also consider the low-growing Vaccinium species as they are excellent groundcover plants or useful in rock gardens. The deciduous species tend to have brilliant fall colors.

| Table 4. Blueberries and Cranberries (Vaccinium) for Garden Use | ||

| angustifolium | Lowbush Blueberry | can be used in dry, lean and acidic locations, important food crop, shear every few years, |

| angustifolium ‘Michigan’ | more compact and resistant to leaf spot disease | |

| angustifolium ‘Putte’ | slightly taller and resistant to stem disease | |

| corymbosum | Highbush Blueberry | most common on wetland margins, but adaptable to average soil, plant several varieties |

| macrocarpon | American Cranberry | useful as groundcover in wet locations, adaptable to average soil if not too dry, important food crop |

| vitis-idea | Mountain Cranberry | low and evergreen, prefers cool climates at high elevations, suitable for rock gardens; the subspecies ‘Minus’ is dense and compact |

Mountain Cranberry is a good garden plant as long as soil is acidic. The variety ‘Minus’ forms a compact evergreen mound. Small white flowers nourish specialist bees, and red berries will be eaten by birds later in the summer. Photo: Thomas Berger

Recommended Dogwood Species

Dogwoods (Swida, formerly Cornus) nourish four specialist bees (besides numerous generalist bees) and 118 caterpillars, as well as several species of aphids, plant bugs, beetles, flies, grasshoppers, and sawflies. The fruit are eaten by birds, and the plants are also consumed by deer, rabbit, and beaver.

Silky Dogwood features attractive blue berries that are loved by birds. Flowers and foliage provide food for specialist and generalist bees and various caterpillars. Photo: Thomas Berger

| Table 5. Dogwoods for Garden Use | ||

| Swida (Cornus) | ||

| alternifolia | Pagoda Dogwood | small woodland tree with horizontal layered branches, a multi-season ornamental |

| ammomum | Silky Dogwood | shrub for wet soil |

| racemosa | Grey Dogwood | large shrub for wet soil |

| rugosa | Round-leaved Dogwood | shrub, adaptable to drier conditions |

| sericea (stolonifera) | Red-Osier Dogwood | widespread as a garden shrub, many varieties found in the nursery trade |

| Benthamidia (Cornus) | ||

| florida | Flowering Dogwood | highly ornamental tree |

Of the native species the Red-Osier Dogwood is a common garden shrub valued for the reddish or yellow winter bark. Cultivars include ‘Flaviramea’, ‘Cardinal’, ‘Arctic Fire’, ‘Silver and Gold’, ‘Aleman’s Compact’ and ‘Kelsey Dwarf’ and offer a variety of sizes, bark and foliage colors.

Non-native Dogwoods are very similar in appearance and include plants that are found in the nursery trade under the names Cornus alba, sanguinea and siberica, including widespread varieties like ‘Arctic Sun’, ‘Argenteo-marginata’ and ‘Ivory Halo’. Due to their possibly different chemistry they should be avoided.

Recommended Goldenrod Species

Among the herbaceous plants the goldenrods are in a class of their own. No other genus is as sought-after both by lepidopteran caterpillars and by specialized bees.

While the willows start the season for the pollinating insects, the goldenrods are the great food source to end the season. In the fall, migratory butterflies like Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) and Monarch (Danaus plexippus) are diligently feasting on goldenrods to get ready for their great journey south. It is possible that goldenrods are as important to the survival of the monarch as milkweeds!

Well over 20 species of Goldenrods are found in NE alone, and they vary considerably in size, attractiveness, aggressiveness and habitat requirements.

Goldenrods have sticky pollen that do not become airborne and are not responsible for pollen allergies. Instead pollen allergies are often caused by ragweed.

| Table 6. Goldenrods (Solidago) for Garden Use | ||

| caesia | Blue-stemmed Goldenrod | under 3 ft. tall, sulphur-yellow flowers, a well-behaved woodland species also suitable for garden plantings, tolerates dry shade |

| flexicaulis

|

Zigzag Goldenrod | over 4 ft. tall, spreading, tolerates dry shade, good for open woodlands |

| flexicaulis ‘Variegata’ | Variegated … | yellow leaf patches can be an overkill! |

| nemoralis | Gray Goldenrod | smaller, later blooming than others and therefore one of the latest sources of nectar and pollen |

| odora | Sweet Goldenrod | dry open woods, colonists drank a tea made from Solidago odora and Ceanothus americanus |

| rigida | Stiff Goldenrod | over 5 ft. tall, clump-forming, good foliage-flower contrast, with flat-topped flower clusters, prefers moist soil, a good garden plant |

| rugosa

|

Wrinkle-leaved Goldenrod | reaches more than 8 ft. in height, spreading, important for its late bloom into November |

| rugosa ‘Fireworks’

|

Fireworks … | under 5 ft. tall, refined, arching clumps, slowly spreading, prefers moist soil |

| sempervirens

|

Coast-Goldenrod | vigorous plants with fleshy foliage, tolerant of salt and drought, perfect for coastal plantings |

| speciosa

|

Showy Goldenrod | an attractive goldenrod that is adaptable to dryer locations, woodland edges, sandy meadows |

Canada Goldenrod (S. canadensis) spreads aggressively and is not suitable for garden use. Photo: Thomas Berger

Most gardeners would probably prefer Solidago rigida and speciosa for ornamental purposes S. sphacelata, including the very compact garden variety ‘Golden Fleece,’ is native west and south of Virginia. An alien species found in the nursery trade is S. virgaurea (syn. S. brachystachys) from Eurasia. Some garden varieties (‘Golden Baby’ and ‘Baby Sun’) are hybrids of unknown parentage and are best avoided in native plantings.

Recommended Aster Species

Closely related to goldenrods are the asters, which lend their name to the entire family, the Asteraceae. Like many other genera in this family, Asters are important plants for both generalist and specialist bees, as well as many other pollinating insects. Caterpillars of the Pearl Crescent (Phyciodes tharos), the Isabella Tiger Moth (Pyrrharctia isabella), the Aster Flower Moth (Schinia arcigera), the Wavy-lined Emerald (Synckora aerata), and many others feed on the foliage of Asters.

According to a recent overhaul of this group of plants the native Asters are now found under the names Symphyotrichum, Eurybia, Doellingeria, Oclemena, Sericocarpus, and Ionactis. Garden varieties have been found to frequently be hybrids of different species, and a classification into three different “cultivar groups” has been suggested.

Because of the uncertainty to which species some of the garden varieties of aster belong, and because of the strong possibility that alien species are part of the mix, they are best avoided in the wildlife garden and are therefore not included in the following table. An example for this is Aster ‘Schneegitter’, formerly classified as Aster ericoides ‘Schneegitter’, a name that is incorrect as it is a hybrid with unknown contributions. It is more correctly listed as “Aster ‘Schneegitter’ (Universum Group)” (as seen in the catalog of Van Berkum Nursery).

| Table 7. Asters for various garden situations: | ||

| Symphyotrichum novae-angliae | New England Aster | one of the most beautiful asters, but relatively demanding, prefers moist soil and full sun |

| Symphyotrichum novi-belgii | New York Aster | similar requirements as New England Aster |

| Symphyotrichum cordifolium | Heart-leaved Aster | adaptable, blooms and grows in shade as well as in sun |

| Symphyotrichum dumosum | Bushy Aster | an adaptable plant frequently used in the perennial garden |

| Symphyotrichum laeve | Smooth Aster | a drought-resistant plant found on sandy and rocky soil; native north to southern Maine; flowers are often purple or blue, foliage feels waxy |

| Symphyotrichum oblongifolium | Aromatic Aster | this vigorous Aster is useful for mass-plantings; native from Montana to New York |

| Eurybia divaricata | White Wood Aster | can be used for mass plantings in woodlands, spreads by rhizomes and is too aggressive for typical garden situations |

| Eurybia macrophylla | Large-leaved Wood Aster | adapted to dry woodlands, large foliage can be effective as a groundcover |

| Doellingeria umbellata | Tall white-aster | slowly spreads to form a colony, suitable for meadows and pollinator gardens |

Alien plants found in New England, either in the wild or in garden centers, are Aster alpinus, tartaricus, thompsonii, x frickartii, Callistephus chinensis (formerly Aster chinensis) and others.

Recommended Native Sunflowers

Besides the Garden-Sunflower, there are other Helianthus species native to North America, most of which are wildflowers of the prairies. Some of these sunflower species reach the Northeast in their northern limits, where they occur in meadows and woodland clearings.

| Table 8. Native Sunflowers (Helianthus) of the Northeast | ||

| decapetalus | Ten-petaled Sunflower | floodplains and forest edges, prefers evenly moist soil |

| divaricatus | Woodland Sunflower | more tolerant of dry and sandy soil and partial shade; |

| giganteus | Tall Sunflower | reaches NY |

| strumosus | Pale-leaved Sunflower | found in forests, meadows and fields, adaptable |

The Garden-Sunflower or better called Field-Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) is a field crop that, like corn, was bred by Native American farmers and spread around the continent. It is not native to the Northeast; however, it is probably still a suitable plant for the specialist bees of our area as they are largely the same species as further south. The same is true for the Tuberous Sunflower (H. tuberosus /Jerusalem Artichoke).

Additional Plants of High Value for Insect Gardens

To offer abundant food sources to insect wildlife throughout the growing season, it is necessary to expand the plant palette beyond the six plant genera described above as superfoods for the insect garden. We gardeners can consciously choose plants that fit both the insects’ needs and our longing for garden beauty.

Table 9 identifies additional garden-worthy woody plants that support both bees (including some specialist bees) and lepidopteran caterpillars as well as other wildlife. Table 10 lists herbaceous plants that are important to specialist bees. Use only the native species of these genera.

| Table 9. Other Garden-worthy Woody Plants to Support Insects | |

| Ceanothus americanus | New Jersey Tea |

| Cephalanthus occidentalis | Buttonbush |

| Ilex verticillata, laevigatam, mucronata, opaca | Winterberry, Inkberry, Mountain Holly, American Holly |

| Malus (natives and alien garden varieties) | Crabapple (even alien crabapples are found to support the native lepidopteran caterpillars!) |

| Myrica pennsylvanica | (used by leafcutter bees for nesting material) |

| Physocarpus opulifolius | Common Ninebark |

| Rhododendron prinophyllum, periclymenoides, viscosum, maximum | Rhododendrons and Azaleas (native to the Northeast) |

| Rosa virginiana, caroliniana, palustris | Virginia Rose, and others, but not Rosa rugosa (non-native and invasive!) |

| Table 10. Other Garden worthy Herbaceous Plants to Support Insects | ||||

| Agalinis | Gerardia | Oenothra | Evening Primrose | |

| Calystegia | False Bindweed | Packera | Groundsel | |

| Campanula | Bellflower | Penstemon | Beardtongue | |

| Cirsium | Thistle | Phacelia | Scorpion-weed | |

| Claytonia | Spring-beauty | Polemonium | Jacob’s-ladder | |

| Erythronium | Trout-lily | Pontederia | Pickerel Weed | |

| Geranium | Cranesbill | Potentilla | Cinquefoil | |

| Helenium | Sneezeweed | Rudbeckia | Black-eyed Susan | |

| Heuchera | Coral Bells | Uvularia | Bellwort | |

| Hibiscus | Rose-mallow | Verbena | Vervain | |

| Houstonia | Bluet | Viola | Violet | |

| Lysimachia | Loosestrive | Zizia | Golden Alexanders | |

| Monarda | Bee Balm | |||

Sources of information

Websites

https://gobotany.newenglandwild.org/genus/Salix, best regional plant information

http://www.bringingnaturehome.net/what-to-plant.html, links to Doug Tallamy’s research

http://www.wildones.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Caterpillars-Moths-and-Butterflies.pdf

http://jarrodfowler.com/specialist_bees.html, study about specialist bees

http://www.nativebeesofnewengland.com, list of New England bee families and genera

https://www.sharpeatmanguides.com, excellent bee images and information

http://greatpollinatorproject.org, good introduction into bees

https://xerces.org, resources to support pollinators

https://www.flickr.com/photos/usgsbiml, focus-stacked bee images by S. Droege

https://crownbees.com, information about hosting bees

http://www.illinoiswildflowers.info, plants and their faunal associations

https://www.chicagobotanic.org/downloads/planteval_notes/no15_goldenrods.pdf

https://bugguide.net/node/view/15740, insect and spider ID assistance

http://www.discoverlife.org, identification guides and more

http://www.catalogueoflife.org, listing of the worlds species

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40198192_Cultonomy_of_Aster_L

Books

Allen M. Armitage, Armitage’s Native Plants for North American Gardens, Timber Press, 2006

Eric R. Eaton & Ken Kaufman, Field Guide to Insects of North America, Hillstar Editions L.C., 2007

Ted Elliman and the New England Wildflower Society, Wildflowers of New England, Timber Press, 2016

Heather Holm, Pollinators of Native Plants, Pollination Press, 2014

Heather Holm, Bees, Pollination Press, 2017

John Laird Farrar, Trees of the Northern United States and Canada, Iowa State University Press, 1995

Donald J. Leopold, Native Plants of the Northeast, Timber Press, 2005

Douglas W. Tallamy, Bringing Nature Home, Timber Press, 2012

The Xerces Society, Attracting Native Pollinators, Storey Publishing, 2011

Wilson, Joseph S. & Olivia Messinger Carril, The Bees in Your Backyard, Princton University Press, 2016

Recommendations for pollinator gardens for the Northeast

http://www.xerces.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/NortheastPlantList_web.pdf

https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs144p2_027028.pdf

About the Author

Thomas Berger grew up in a small rural town in Germany. During his childhood he was an avid collector of shells, bones, sea creatures, and fossils. He also gardened with his father and kept bees and sheep which led him to study agriculture. As an adult, Thomas worked on farms in Germany, France and Australia, and joined the German Volunteer Service in 1984, working in an agricultural project in Niger, West Africa. In 1994 he moved to the United States, where he started a landscape design and construction firm, Green Art, and received an award of excellence from the New Hampshire Landscape Association in 1998. Thomas is a regionally known stone sculptor, expressing his love of nature through his art. Thomas has won many awards and commissions, and his sculpture is displayed at public venues throughout the Northeast.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.