by Beka Sturges

How do you approach a project? How do you conceive it? How do you represent it? What is at stake? Over the past 15 or so years that Reed Hilderbrand has been involved with The Clark Art Institute, we have asked these questions of ourselves. And been asked these questions and more by the community, by students, by curators, and by visitors to the museum.

The answers change. And we are still at work and still coming to understand what the answers might be. Often we tell the story of creating a cultural commons, of turning the museum toward the land, of shaping a new landscape, one that revives the pastoral history of the site and casts it forward. As one visitor noted, now, at The Clark, “the landscape is the protagonist.” It acts. It has presence. It is working, a working landscape for the 21st century.

We were hired to help The Clark with its expansion, with circulation and parking. It sounded like a simple brief.

A view to the east of the Clark Art Institute shows the Museum and Manton Research Center. Photo: James Ewing

A Developing Story

Site plan.

True the land was laced with wetlands and, true, there were steep slopes in most directions. Forest covered half the 140 acres, and the giant meadow of Stone Hill had a kind of sacred status and couldn’t be touched.

What we intuited at the start and came to appreciate with deepening respect each year, was that this land, this spot, this 140 acres had value. It was loved as a site for studying forests, as a place to walk your dog, as a place to run naked in the dark, as a place to skate with your family in the winter. For the community, it was a park and a gateway into the wilderness. For the museum, it was not a celebrated asset though. Yes, the views of Schow Pond from the gallery windows resonated with the Impressionist landscape paintings visitors saw on the walls, but there was not a larger curatorial story about the land.

We realized that we had to bridge not just the wetlands, but different ways of perceiving and valuing the land – its power, its life, its systems.

Connecting with Woods

Birch and Aspen Thicket. Photo: Alan Ward

The project unfolded in two phases. The first phase, which involved a new building, The Lunder Center for the Williams Art Conservation Center, meant analyzing the site closely and bringing a surgical precision to carving into the existing woods and crossing over the meandering streams. Here we began our efforts to reframe the land, to rebuild the story of the site, and to introduce science and green infrastructure to what was largely understood as a question of fine arts conservation and architectural expression.

How do you make a clearing? How do you ensure habitat value? How do you rebuild a forest? And then once you have your clearing, how do you minimize impervious surfaces? How can you use structural soils for mechanical access, for fire truck turnarounds, for parking? How can you use green roofs for sculpture and water management? How can you provide for infiltration and water quality treatment in a way that creates beauty and hosts events?

What we learned in this phase was the importance of working with the local conservation commission, with scientists who conducted research in the Stone Hill woods, with our civil engineers, and with our soils scientists to build a terraced clearing that opened views, gave access to the forest, enhanced habitat, and improved water quality. We began advocating for elements of the design that we could not see – what was underground. We began advocating for an integrated approach, where the systems that enable occupation are designed with the same care and accountability as the spaces and surfaces of the museum. Where the work of a tree is understood to have value for the functioning of the museum systems.

Path around Schow Pond. Photo: James Ewing

Trees were not considered as merely visual elements in the background or foreground. The shade they provided minimized heat island effects and reduced irrigation demands. And trees weren’t just part of a design offset to satisfy the demands of the tree huggers. They were part of a renewed stewarding of the land.

Connecting with Water

Land Bridge and Weirs at the Pools. Photo: Millicent Harvey

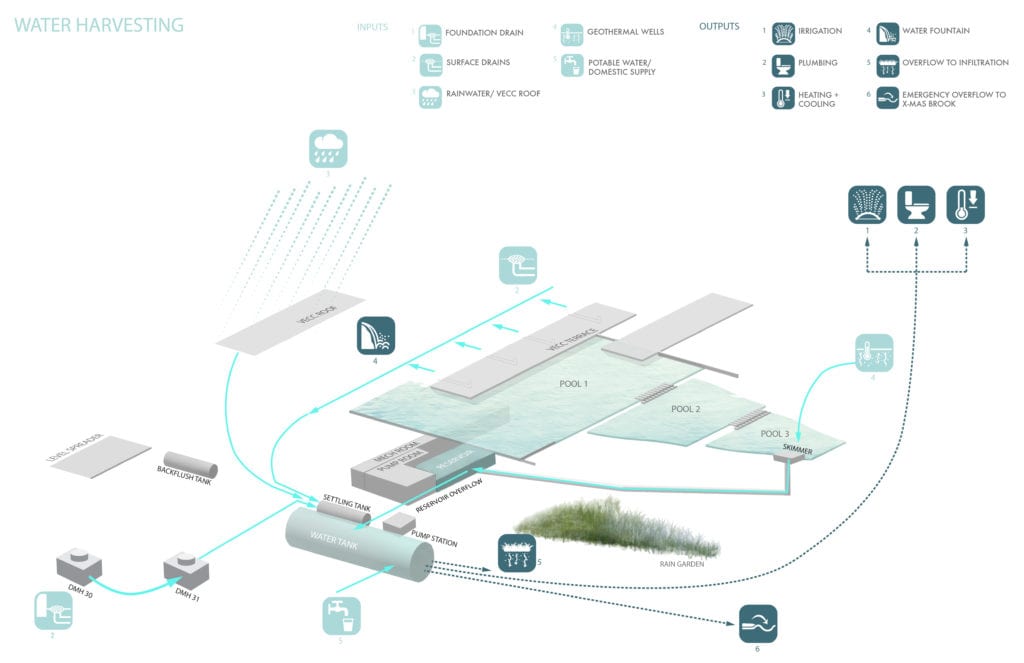

The second phase of the project involved greater innovation and reframing of existing assets. Water became the celebrated resource. Circulation shifted to embrace the Schow Pond and tie to the trails. A cascading series of reflecting pools created a center for gathering and watching or for starting out into the woods or meadows. The pools capture rainwater and make use of the foundation water. A shared reservoir and coordinated pair of rainwater harvesting tanks depend on a digital Building Management System to disperse water to plumbing, geothermal makeup, infiltration, irrigation, and the pools. The systems for the building and the systems for the landscape are intimately interwoven and responsive to shifting demands and resources.

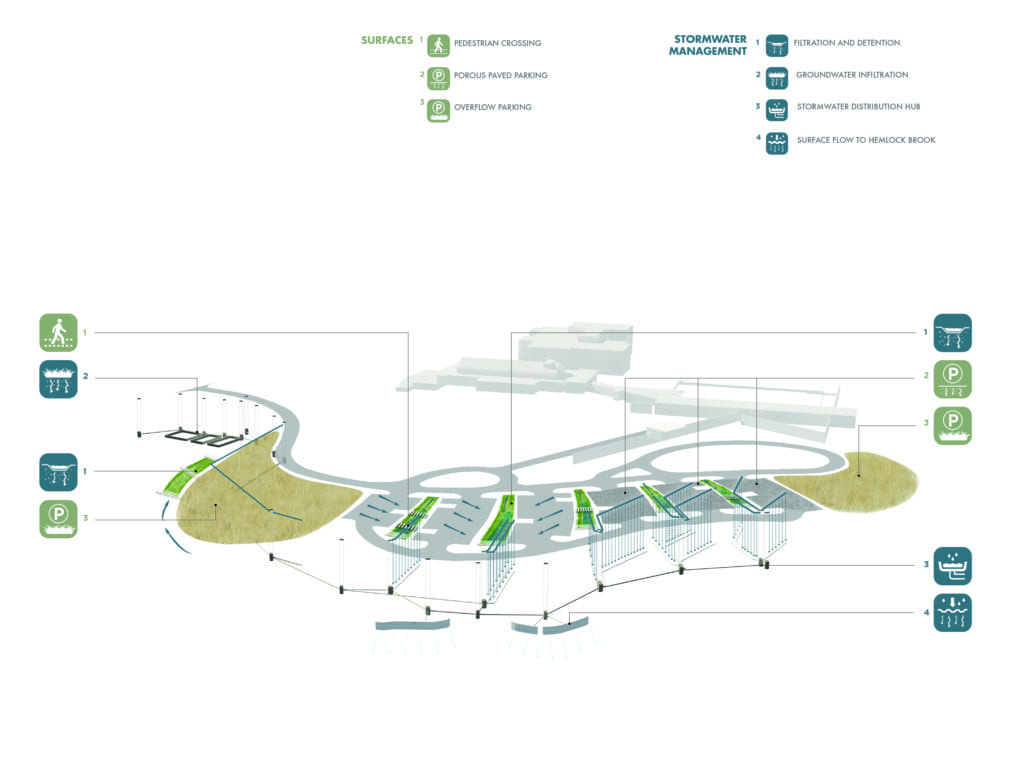

In this phase, parking, which had acted as a dam dividing the museum from the woods and meadows, was removed from the west side of campus. Relocated to the north and interwoven with generous planting areas for trees, meadow grasses, and bioinfiltration basins, the new parking linked the arrival sequence to Stone Hill meadow. Two large meadow parking areas fulfill the heavy seasonal demand for parking in July and August, and porous asphalt infiltrates water in the zones with decent percolation rates.

The mechanisms and methods for integrating landscape systems and performance at The Clark are extensive. Some are well tested and proven and some are pilot projects. Immersing visitors in a working landscape that brings them joy has had the unexpected consequence of many people asking how it works. Through exhibitions about landscape and by commissioning and testing its own landscape, the Clark has begun to answer that question.

Diagram of the Water Management at the North Parking Area

About the Author

Beka Sturges is an Associate Principal of Reed Hilderbrand at their New Haven, CT office. She holds a Master of Landscape Architecture from Harvard Graduate School of Design. While at Harvard she received the Charles Eliot Traveling Fellowship to research urban agriculture sites in South America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Beka joined Reed Hilderbrand in 2004. She is also a Visiting Assistant Professor of Art and Art History at Connecticut College and regularly serves as a guest critic at Yale School of Architecture.

***

Each author appearing herein retains original copyright. Right to reproduce or disseminate all material herein, including to Columbia University Library’s CAUSEWAY Project, is otherwise reserved by ELA. Please contact ELA for permission to reprint.

Mention of products is not intended to constitute endorsement. Opinions expressed in this newsletter article do not necessarily represent those of ELA’s directors, staff, or members.